Partial range of motion bench presses. Do they help build more full range of motion bench press strength, and do they have any benefit for muscle hypertrophy?

In this article, the partial range of motion bench press refers to performing only some part of the top range of motion, where the chest, anterior deltoid, and triceps are at a more shortened length.

Although, we will discuss a partial range of motion bench press that trains only the bottom range of motion, where the muscles are more lengthened, later on.

A full range of motion bench press, of course, refers to moving the barbell from more or less full elbow lockout to down the chest.

Table of Contents

- Potential Reasons Supporting Partial Range of Motion Bench Press

- The Scientific Research: Partial vs Full Range of Motion Bench Press

- The Principle of Specificity Is Violated With Bench Press Training?

- Partial vs Full Range of Motion Bench Press for Hypertrophy

- So, Is the Partial Range of Motion Bench Press Completely Useless?

- Summary of This Large Article

Potential Reasons Supporting Partial Range of Motion Bench Press

A couple of reasons exist behind why a partial range of motion bench press could be beneficial for gains.

Firstly, partial range of motion bench presses enable you to lift much heavier loads than you could with a full range of motion bench press. This could be useful for gaining confidence with handling and moving heavier loads, thereby perhaps indirectly helping full range of motion bench press performance.

Secondly, within your muscles are something called Golgi tendon organs. High muscle force production can highly stimulate Golgi tendon organs.

In response, Golgi tendon organs ultimately signal to the nervous system to reduce the number of electrical signals sent to the muscle, thus reducing force output.

It’s believed the purpose of all of this is to protect the muscle and tendons from excessive damage.

As you can train with much heavier loads on partial range of motion bench presses, this could “desensitize Golgi tendon organs”, therefore allowing you to more effectively train with heavier loads on the full range of motion bench press.

Thirdly, the heavy loads with partial range of motion bench pressing could generally just enhance neural adaptations.

In this context, neural adaptations are changes that allow the nervous system to send more electrical signals to a muscle, thereby allowing the muscle to generate more force.

Some evidence indicates training with heavier loads produces these neural adaptations more than lighter loads. Resultantly, perhaps partial range of motion bench press training produces neural adaptations that would enable you to lift heavier loads with full range of motion bench presses.

As for hypertrophy, both Golgi tendon organ desensitization and enhanced neural adaptations might be beneficial.

As noted, both of these things would essentially increase the amount of force we could exert with a muscle. Put another way, those adaptations enable us to expose the muscle to more tension.

This is perhaps notable as tension is probably the best-categorized driver of muscle hypertrophy at this time.

As a result, this is a potential route by which partial range of motion bench press training might benefit hypertrophy.

The Scientific Research: Partial vs Full Range of Motion Bench Press

So, although the three mentioned reasons sound plausible, do they actually occur in reality?

That is, does the partial range of motion bench press training have any strength or hypertrophy benefit?

Unfortunately, no study (as far as I know) has explored how a partial range of motion bench press compares to a full range of motion one for hypertrophy, or if there’s any benefit to combining both ranges of motions for hypertrophy.

All of the studies have examined strength outcomes only.

Despite this, we will be using indirect data to speculate on how a bench press with a partial range of motion may compare to a full range of motion a little later.

Nevertheless, let’s dive into the current research.

Martinez-Cava et al.

Subjects

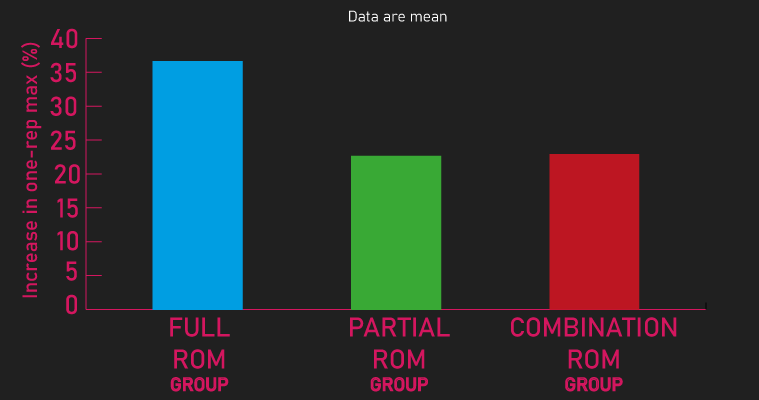

Martinez Cava et al. recruited 49 men with 6 months of training experience and allocated them into a full range of motion, 2/3 range of motion, 1/3 range of motion, or control group.

We won’t discuss the control group from hereafter. They did not train and expectedly made virtually no gains.

Protocol

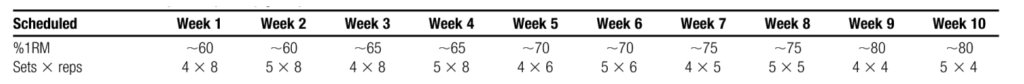

All groups trained on the smith machine barbell bench press twice per week for a total of 10 weeks.

Repetitions for the full range of motion group were as follows: they lowered the barbell from full elbow lockout all the way down to the chest, where they momentarily let the bar rest for 2 seconds thanks to the smith machine spotters, before reversing the motion.

The 2/3 range of motion group lowered the barbell from full elbow lockout to only 2/3rd of the way down to the chest, where they momentarily let the barbell rest for 2 seconds thanks to the smith machine spotters, before reversing the motion.

The 1/3 range of motion group lowered the barbell from full elbow lockout to only 1/3rd of the way down to the chest, where they momentarily let the barbell rest for 2 seconds thanks to the smith machine spotters, before reversing the motion.

All subjects performed their repetitions with a maximal intended lifting speed and a controlled lowering speed.

This was a velocity-based study, meaning the velocity of each lifting phase was recorded via special equipment.

For each individual, as there’s a relationship between the lifting velocity during the 1st repetition on a set and the relative load you’re using, the subjects were able to autoregulate and train with the loads they intended to.

The exact reps, sets, and loads used throughout the 10 weeks are shown below.

Of course, the relative loads used for each group are specific to the range of motion they trained with. For example, when the full range of motion group trained with a 70% one-rep max load, that 70% one-rep max load is 70% of their one-rep max on the full range of motion bench press.

Whereas a 70% one-rep max load for the 1/3 range of motion group would have been 70% of their one-rep max on the 1/3 range of motion bench press, and for the 2/3 group, the 70% one-rep max load would have been 70% of their one-rep max with a 2/3 range of motion bench press.

Measurements

Before and after the study, a range of strength and power measurements were assessed.

Most relevant for our purposes, all 3 groups had their one-rep maxes on the full range of motion bench press, 1/3 range of motion bench press, and 2/3 range of motion bench press tested.

The researchers opted to express one-rep max gains relative to the participant’s body weight.

Results

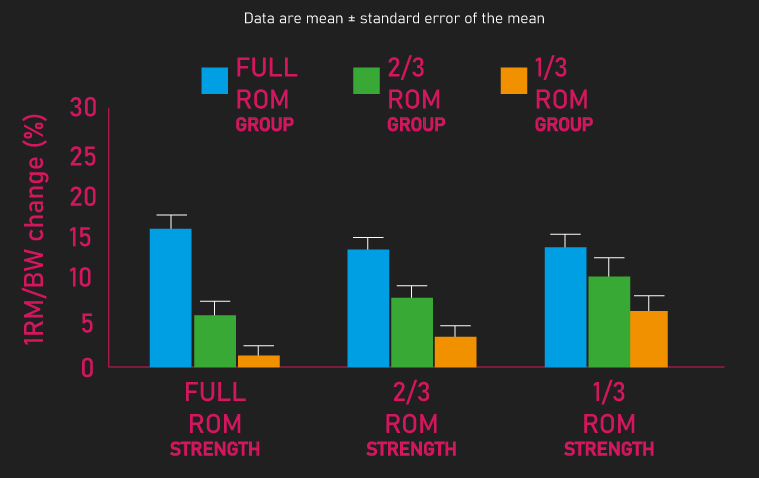

What they found was the full range of motion group saw the greatest gains in one-rep max to bodyweight ratios for all three bench press variations. Also, the 2/3 group saw greater one-rep max to bodyweight ratio gains compared to the 1/3 group.

Stated another way, training with the full range of motion bench press (which is what the full range of motion group did) was the most effective for increasing full range of motion bench press, 2/3 range of motion bench press, and 1/3 range of motion bench press one-rep max to bodyweight ratios.

Also, training with a 1/3 range of motion bench press (which is was the 1/3 range of motion group did) was the least effective for increasing one-rep max to bodyweight ratios on all three of the bench press variations.

These findings are highly interesting. Not only do they indicate a full range of motion bench press is superior for increasing full range of motion bench press strength, but a full range of motion bench press is also better for increasing partial range of motion bench press strength versus training with that specific partial range of motion itself.

Two Studies by Massey et al.

But, what does the other data say?

There are two other studies, both conducted by Massey et al. (one & two)

Subjects

In one of these studies, 56 men were recruited, while in the second study, 29 women were recruited.

The researchers were not specific on the training history of the subjects. But, the 56 men had some experience, and they seemed to range from those who worked out frequently at moderately high-intensity levels to those who worked out occasionally or infrequently.

The 29 women were described as having limited experience, with the majority working out occasionally or infrequently.

Protocol

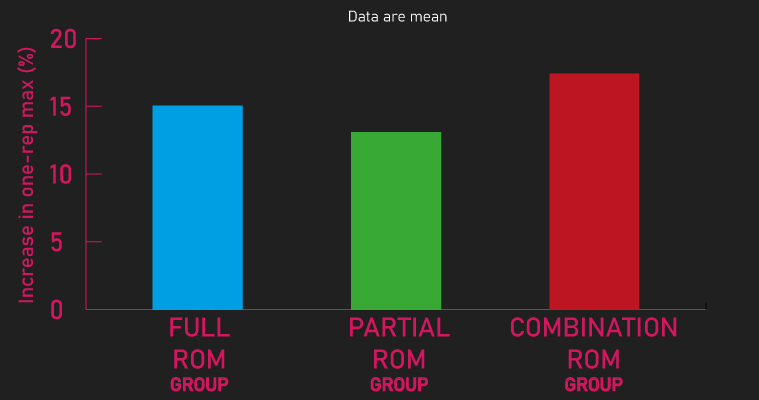

In both studies, subjects were assigned into a full range of motion, partial range of motion, or combined group.

All groups trained 2x per week for 10 weeks.

The full range of motion group, each session, trained the full range of motion barbell bench press for 3 sets of 15 repetitions with a 65% one-rep max load. That 65% one-rep max load was relative to their full range of motion one-rep max.

The partial range of motion group, each session, only performed the top 2-5 inches of the barbell bench press, for 3 sets of 15 repetitions with a 100% one-rep max load. That 100% one-rep max load was relative to their full range of motion one-rep max.

The combined group, for each session in the first 5 weeks, performed the aforementioned partial range of motion bench press for 2 sets of 15 repetitions with a 100% one-rep max, and the aforementioned full range of motion bench press for 1 set of 15 repetitions with a 65% one-rep max load.

During the final 5 weeks, this was reversed. They performed 2 sets of 15 repetitions with a 65% one-rep max load on the full range of motion bench press, and 1 set of 15 repetitions with a 100% one-rep max load on the partial range of motion bench press.

All groups rested 2 minutes between sets, and when subjects were able to, the load was increased by 5lbs next session to try to maintain the same relative loading.

Measurements

Before and after the study, all groups were tested only in their full range of motion bench press one-rep max.

Results

In the first study, the one comprised of 56 men, increases in full range of motion bench press one-rep max were not statistically different between any of the three groups.

In the second study, the one comprised of 29 women, increases in full range of motion bench press one-rep max was greater for the full range of motion group versus the two other groups.

Takeaway From the Studies

So, when overviewing the three studies, there are technically conflicting findings amongst them. It’s not definitively clear why this is, but perhaps the different subject demographics used in the various papers could play an explanatory role.

Despite this, I still think there are some potential conclusions we can draw from this data.

In all of the studies, training with a full range of motion bench press was not worse for any outcome.

In the Martinez-Cava study, training a full range of motion bench press was better for increasing strength to bodyweight ratios across three different bench press ranges of motion when compared to training with only partial range of motions.

In the two Massey et al. studies, neither training with only partial range of motion bench presses, nor training with a combination of partial and full range of motion bench presses, was superior for increasing full range of motion bench press one-rep max compared to training with a full range of motion bench press.

As a result, these studies largely fail to support the idea that partial range of motion bench press training (either exclusively or in combination with full range of motion bench press training) is superior.

Therefore, it seems our previous speculations as to why a partial range of motion bench press could be beneficial (particularly the Golgi tendon desensitization and neural adaptations) are not supported.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

The Principle of Specificity Is Violated With Bench Press Training?

Quite fascinatingly, all three studies oppose the principle of specificity.

The principle of specificity, in our context, states you would experience the greatest strength gains on the exercise you train.

Training the full range of motion bench press should produce the largest full range of motion bench press one-rep max gains, while training a partial range of motion bench press should produce the largest partial range of motion bench press one-rep max gains.

In the Martinez-Cava study, the full range of motion group did experience the greatest strength to bodyweight ratio gains on the full range of motion bench press, in line with the principle of specficity. However, this group also saw greater strength to bodyweight ratio gains on the 1/3rd and 2/3rd bench presses compared to the two other groups that actually exclusively trained with those exercises, opposing the principle of specificity.

In the Massey et al. study conducted on men, training with a partial range of motion bench press only, or training with a combination of full and partial range of motion bench presses, was no less effective for increasing full range of motion bench press one-rep max gains than training exclusively with a full range of motion bench press, thus opposing the principle of specificity.

This data demonstrates how the principle of specificity is not an irrefutable law.

What could explain the unreliability of the principle of specificity with the barbell bench press?

There is no definitive answer to this. But, I came across an article by Greg Nuckols of Stronger by Science in which he puts forth a very strong potential suggestion.

He speculates that the strength fluctuations throughout a range of motion might matter. Let’s explore this more.

In an exercise such as the barbell back squat, it’s not uncommon for individuals to be significantly stronger with partial squats (performed at short muscle lengths) than full range of motion squats.

Greg gives us an example. When his full range of motion squat was around 650lbs, he could quarter squat over 1000lbs.

Indeed, when looking at the literature on back squats, training will a full range of motion produces the largest full range of motion squat one-rep max gains, while training with a partial range of motion squat produces the largest partial range of motion squat one-rep max gains. This is in accordance with the principle of specificity.

Contrasting to all this, looking at a bench press, the amount of weight you can handle with a partial range of motion is not substantially greater than what’s used with a full range of motion, as is the case with the squat.

For instance, in the Martinez-Cava et al. study, individuals were full range of motion bench pressing around 165lbs-175lbs, while their partial 1/3rd range of motion bench press was around 257 to 260lbs on average.

Perhaps this, the fact that there may not be such a massive loading difference between different ranges of motions on the bench press, explains why the mentioned studies did not unanimously support the principle of specificity.

Training with a full range of motion bench press may be sufficiently capable of producing large partial range of motion bench press gains, and vice versa.

Partial vs Full Range of Motion Bench Press for Hypertrophy

Moving forward, what about hypertrophy?

As noted earlier, there are unfortunately no data (I’m aware of) that’s examined how any kind of partial range of motion bench press compares to a full range of motion one for hypertrophy. But, there is indirect data that’s helpful.

I think it’s more than likely a full range of motion bench press would build more muscle than a partial range of motion that trains only the top portion of the bench press.

I say this as a full range of motion bench press would stretch the chest, anterior deltoid, and triceps under load way more than a partial range of motion bench press that trains only the top portion.

This is notable as the current data indicates achieving a stretch under load is powerful for stimulating muscle hypertrophy.

For example, a range of studies has found that compared to performing exercises with a partial range of motion that trains the muscle(s) at a short length, using a fuller range of motion evokes more muscle hypertrophy.

Additionally, compared to a partial range of motion at short muscle lengths, a partial range of motion at long muscle lengths appears to be much more effective for muscle hypertrophy.

Now, this data does not necessarily mean a partial range of motion per se on the bench press is suboptimal.

What I mean by this is a partial range of motion that trains the lower portion of the bench press may be similarly effective to a full range of motion bench press, as this type of partial range of motion would load the chest, triceps, and anterior deltoid under stretch.

In fact, some evidence may potentially suggest this type of partial range of motion would be superior.

More precisely, a study by Pedrosa et al. (which we’ve overviewed in a previous article) actually found that a partial range of motion leg extension at long quadriceps lengths produced overall more quadriceps growth than a full range of motion leg extensions.

Of course, this study used a leg extension. Thus, we cannot be certain these findings can be replicated with the bench press. Future data would be required to establish this.

So, Is the Partial Range of Motion Bench Press Completely Useless?

As a final section of this article, does all of the research overviewed in this article indicate a partial range of motion that trains the top portion of the bench press is completely useless for anything?

Not necessarily.

Under certain circumstances, a combination of both full range of motion bench presses and partial range of motion bench presses that train the top portion, could be useful for strength.

Let me explain.

As we’ve already overviewed, both Massey et al. studies failed to find a benefit to combining both full and partial range of motion bench press training for the purposes of increasing full range of motion bench press one-rep max.

However, both studies were likely not conducted on individuals with extensive training experience, as alluded to earlier.

For individuals with extensive training experience, and perhaps more importantly, with those that have their sticking point on the bench press closer to lockout, added partial range of motion bench press training near the top portion might be beneficial.

The sticking point of an exercise is the hardest part in the range of motion. When lifting near maximal loads or nearing failure, it’s the part of the range of motion where the weight moves the slowest despite maximal or constant effort.

When you fail to complete a repetition, you would fail within this sticking point.

For most individuals, it seems the sticking point for the barbell bench press is closer towards the bottom and middle portion of the full range of motion. At around the 30-50% point in the lifting phase.

For these individuals, it’s logical that partial range of motion bench press training at the top portion, which is past the sticking point, would not benefit or enhance full range of motion bench press strength.

However, there is evidence some individuals do not actually display a sticking point in the bench press, even at maximal efforts.

These individuals are challenged uniformly throughout the full range of motion, and they could experience failure at any stage.

Furthermore, the grip width you use seems to also impact sticking points.

One paper found that using an approximate 1.65x shoulder-width grip (we’ll call this a medium grip) resulted in a sticking point closer to lockout than using a 2.25x shoulder-width grip (a wide grip) or 0.95x shoulder-width grip (a narrow grip).

Based on this, if you’re an individual who does not have a consistent sticking point and/or your sticking point is closer towards lockout (perhaps due to grip width), it’s possible added partial range of motion bench press training near the top region could be beneficial for eventually enhancing your full range of motion strength.

Now, some of you may be thinking “Wait a minute, didn’t the Martinez-Cava et al. study find that full range of motion bench press training was superior for increasing partial range of motion bench press strength compared to training with that partial range of motion itself?”.

Resultantly, partial range of motion bench press training would not be helpful.

This is true, and it is a limitation with the suggestion I’m putting forth.

Moreover, we’ve already established potential reasons as to why this, the fact the principle of specificity is unreliable with the bench press, may be the case.

However, recall that in all three studies we’ve assessed, the subjects were not highly trained. The subjects in the Martinez-Cava study only had 6 months of training experience.

In more trained individuals, though I’m not certain, perhaps the principle of specificity on the bench press becomes more important.

A study by Clark et al. potentially supports this.

22 men with an average bench press one-rep max of 107kg were recruited. Now, it’s not clear if this referred to a free weight barbell bench press or a smith machine bench press. But either way, these subjects were likely more trained than the subjects in the 3 other studies we’ve analyzed.

Subjects were assigned into a variable or full range of motion group.

Both groups trained on the smith machine bench press twice per week for 5 weeks.

The full range of motion group, each session, trained 4 sets of full range of motion bench press repetitions.

The variable range of motion group, each session, trained 1 set of full range of motion bench press repetitions, 1 set of 3/4th range of motion repetitions, 1 set of half range of motion repetitions, and 1 set of 1/4 repetitions.

Before and after the study, both groups used a custom-made isokinetic bench press machine to perform 2 sets of 5 lifting only repetitions.

The average force produced was measured during 3 different phases of the repetitions.

The first phase was from 25-50% of the lifting phase, the second phase was from 50% to 75% of the lifting phase, and the third phase was from 75% to 100% of the lifting phase.

The researchers found that neither group experienced statistically significant increases in force produced during the first and second phases of the repetitions. However, for the third phase, the variable range of motion group did increase the force they produced, whereas the full range of motion group did not.

As a result, this study indicates variable range training (which consisted of some full range of motion and partial range of motion sets) effectively increased the force subjects could generate at the top portion of the bench press range of motion. Full range of motion only training did not do this.

Therefore, for trained individuals who have no real sticking point and could fail at any part of a full range of motion bench press and/or who seem to have their sticking point closer to lockout (perhaps due to grip width), it’s possible partial range of motion bench press training near the top range of motion could be beneficial for ultimately enhancing full range of motion bench press strength.

Summary of This Large Article

Alright, we’ve gone through a lot of information throughout this article. Let us summarize it all to make things crystal clear.

Based on the current data, it seems most individuals probably would not benefit from performing additional or exclusive partial range of motion bench press training near the top range of motion. This is probably especially true if you’re relatively untrained and/or you’re sticking point in the full range of motion bench press is closer to the lower or middle region of the range of motion.

Moreover, for the purposes of hypertrophy, I think it’s likely full range of motion bench pressing, as it achieves a greater stretch under load of the working muscles, would produce greater hypertrophy than partial range of motion bench pressing near the top range of motion.

If you’re a trained individual and you tend not to have a sticking region in the bench press and/or your sticking region is closer to lockout (perhaps due to your grip width), combination training (that is, added partial range of motion bench press training near the top range of motion to your full range of motion bench press training) could potentially be beneficial for enhancing full range of motion bench press strength.

Finally, many questions remain.

For example, could partial range of motion bench press training in the bottom range of motion build more muscle than full range of motion bench pressing?

Also, could partial range of motion bench press training in the bottom range of motion have any benefit for those looking to maximize their full range of motion bench press strength?

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.