The high bar back squat (from hereafter simply called the squat) is one of the most popular lower body exercises.

This exercise can be executed in a variety of ways. Stance width, foot orientation, and depth can all be altered.

Out of these, depth is probably the most commonly debated variable.

It’s easy to come across opinions supporting either side. One side suggests partial range of motion squats maximize the adaptations you experience, while the other side may suggest you’re leaving gains on the table by not performing full range of motion squats.

In this article, I’ll do my best to detail the current literature comparing partial range of motion squats (in this article defined as squats above parallel) to deeper range of motion squats for hypertrophy, strength, and athletic outcomes.

Let’s dive in.

Table of Contents

Partial vs Deep Squats for Muscle Hypertrophy

Starting off with hypertrophy comparisons, there are currently two relevant papers.

Bloomquist et al. recruited 17 men untrained at least in the 6 months leading up to the study and assigned them into a partial or deep squat group.

The partial squat group performed squats from 0 to 60 degrees of knee flexion, while the deep squat group performed squats from 0 to 120 degrees of knee flexion.

Both groups trained their respective exercise three times per week (the program is on-screen) for 12 weeks.

Front thigh cross-sectional area (consisting of the quadriceps, sartorius, and adductors), measured across 6 regions, was all greater for the deep squat group. The partial squat group only experienced growth at the two proximal regions.

Therefore, this study indicates squatting to 120 degrees of knee flexion evokes greater overall growth of the front thigh.

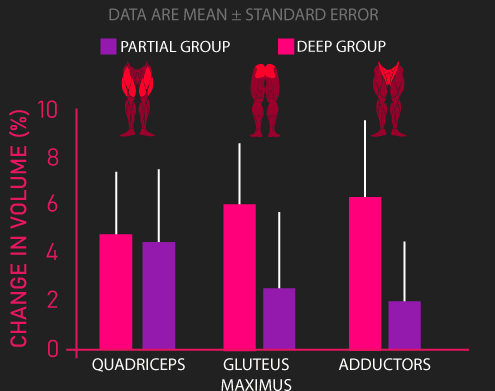

Kubo et al. had 17 men untrained at least in the year leading up to the study assigned into a partial or deep squat group.

The partial squat group performed squats from 0 to 90 degrees of knee flexion, while the deep squat group performed squats from 0 to 140 degrees of knee flexion.

Both groups trained their exercise for 3 sets with roughly an 8 rep-max load, twice per week for 10 weeks.

After the study, quadriceps volume increased similarly in both groups, suggesting 90-degree squats may be a sufficient depth to optimize quadriceps growth.

However, increases in adductor and gluteus maximus volume were significantly greater for the deep squat group, suggesting achieving deep squat depths is necessary to maximize growth of these two muscles.

So, these two studies collectively indicate deeper squat depths are associated with more hypertrophy overall. 60-degree squats in the Bloomquist study failed to optimize growth across many regions of the front thigh, while although 90-degree squats in the Kubo study seemed to be fine for quad growth, they failed to maximize gluteus maximus and adductor growth when compared to 140-degree deep squats.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Partial vs Deep Squats for Strength

Moving on to strength, how do partial squats compare to deep squats for this component?

In total, the literature indicates this follows the principle of specificity.

More precisely, the already mentioned two studies by Bloomquist and Kubo, as well as a study by Rhea et al. and Hartmann et al. indicate one-rep max gains on some form of a partial range of motion squat are greater for the group that trains with that partial range of motion squat versus a group that squats deeper. However, one-rep max gains on a deep squat is greater for the group that trains that deep squat versus a group that trains some form of a partial squat.

Now, in all of these studies, they only assessed how exclusive partial range of motion squat training compares to exclusive deeper squat training?

However, could there be any potential benefit to combining both partial and deeper squats for strength?

A study by Bazyler et al. suggests there might be.

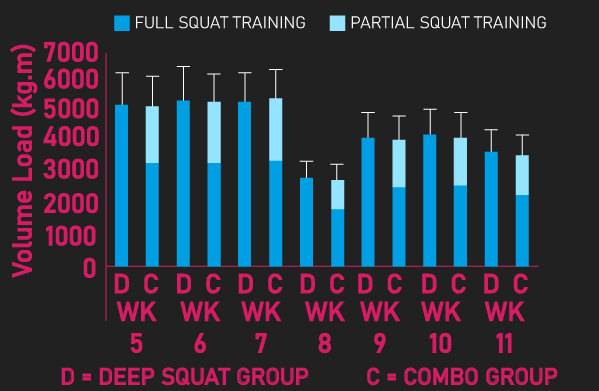

17 men with an average full squat one-rep max of 146.9kg were assigned to a deep squat or combination squat group.

The deep squat group performed full squats (the researchers did not provide further detail), while the combination group performed both full and partial squats (the partial squats were performed to 100 degrees knee flexion).

A block periodized design with heavy and light days was used. Both groups performed similar total volume (in this case, the product of load x range of motion x repetition number) on the squat each week, the only difference being the deep squat group performed only full squats, while the combination group’s volume was divided between full and partial squats.

After 12 training weeks, increases in full squat one-rep max, and partial squat one-rep max (performed to 100 degrees of knee flexion) were greater for the combination group.

Therefore, perhaps full and partial squats synergistically promote one-rep max strength.

However, there are some things worth keeping in mind with this study.

Firstly, the partial squat was performed to 100 degrees of knee flexion, could the same results be obtained with other partial range of motion squats (such as a 60-degree knee flexion squat, for example)?

Secondly, the subjects were trained (recall their average full squat one-rep max before the study was 146.9kg), would the same results hold true for less trained individuals?

Thirdly, this is only a single study. There are no other studies (to my knowledge) with a similar design.

Nonetheless, I think this study’s finding is quite intriguing, and it would be great to see if future studies could replicate it.

Partial vs Deep Squats for Athleticism

Progressing on, how do partial squats compare to deep squats for athletic outcomes such as jumping or sprinting?

Interestingly, your training and athletic experience may be a factor here.

The already mentioned study by Bloomquist et al. found in men who’d not been training in the 6 months leading up to the study, training with 120-degree squats produced greater increases in squat jump and countermovement jump height versus training with 60-degree squats.

Comparably, Hartmann et al. established in men and women with low training experience, full squats produced greater increases in squat jump and countermovement jump height compared to 60 degrees knee flexion partial squats performed in a smith machine.

However, Rhea et al. recruited college athletes who squatted an average of 120-130kg and had an average vertical jump of 73-75cm, as well as an average 40-yard dash between 4.76-4.68 seconds. This group of researchers compared 3 different squat depths: 55-65 degree squats, 85-95 degree squats, and greater than 110-degree squats.

Overall, the partial 55-65 degree squats evoked the greatest increases in vertical jump height and 40-yard sprint speed. Moreover, the 85-95 degree squats also evoked greater increases versus the greater than 110-degree squats.

Integrating these three studies, it seems in individuals with minimal training experience, full squats may be superior for athletic development versus partial squats. But for trained individuals, partial squats may be more favorable.

Having said this, it’s worth noting there are only three studies, and there is only one study conducted on trained individuals, so future research could definitely change these conclusions.

Summary

In summary, deep squats seem to provide a more powerful stimulus for overall muscle hypertrophy.

As for strength, if you want to maximize your deep squat one-rep max, training the deep squat likely achieves this better than training only partial squats. Inversely, if you want to maximize your partial squat one-rep max, training that partial squat likely achieves this better than training only deep squats. As we know, one interesting study suggests combining both deep and partial squats may produce greater deep and partial squat one-rep max gains compared to only training deep squats.

For developing athletic attributes such as jump height and sprint speed, those with minimal training experience seem to experience the best adaptations with deep squats, as opposed to partial squats. But for those with more extensive training experience, partial squats may confer greater gains in these areas.

Do Deep Squats Have a High Risk of Injury?

Before closing out the article, I thought it would be worth touching on injury risks with squats.

It’s far from common to hear that deep squats are unhealthy for spine and knee health.

Now, I should mention I’m by no stretch of the imagination an expert on injuries, but I think it’s worth sharing this extensive review study by Hartmann et al.

The researchers performed a comprehensive analysis on whether deep squats truly possess greater injury risk. Fundamentally, they concluded they did not.

One of the things demonstrated is how adaptable the body is.

For example, the review study details data showing professional weightlifters (who spend a significant time in deep squatting positions) possess significantly higher knee joint cartilage thickness versus untrained individuals. Moreover, other data indicates elite weightlifters possessed 133% higher bone mineral density in the lower back region compared to untrained individuals.

Finally, and quite interestingly, the researchers also suggest that partial squats (due to requiring heavier loads for an effective stimulus( might actually involve a greater injury risk versus full squats.

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.