Strength before size?

Could aiming to increase your strength first, defined as increasing your one-repetition maximum on an exercise, help you build more muscle with that exercise later?

Table of Contents

A new study by Carvalho et al. explored just this.

The Study: Strength Before Size

Subjects:

They recruited 26 men with an average of 4 years and a half years of training experience who could squat at least 1.5 times their respective bodyweight.

Protocol:

Subjects were split into pairs based on having similar vastus lateralis thickness.

In each pair, one subject was assigned to a hypertrophy group while the other subject was assigned to a strength plus hypertrophy group.

Both groups trained twice per week for 8 weeks, training the back squat and leg press each session.

The hypertrophy group, for all of their sessions, trained each exercise with 4 sets of 8-12 reps to failure (the point at which no more repetitions can be performed) and 1 minute of rest between sets.

The strength plus hypertrophy group, for the first 3 weeks, trained each exercise with 4 sets of 1-3 reps to failure and 3 minutes of rest between sets. This was their strength phase.

For the last 5 weeks, they trained identically to the hypertrophy group, so they trained each exercise with 4 sets of 8-12 reps to failure and 1 minute of rest between sets. This was their hypertrophy phase.

I should note that both the hypertrophy group and strength plus hypertrophy group, before this 8-week experimental protocol, had a 3 week lead-in period where they both trained identically. We don’t really need to worry about this.

Measurements:

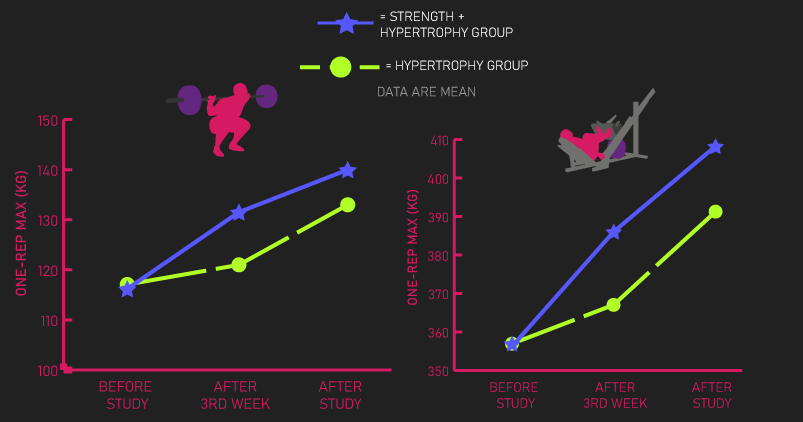

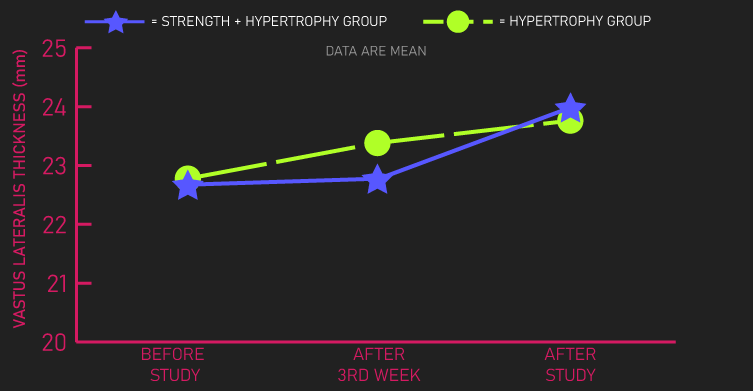

Measurements were taken just before the 8-week experimental protocol, just after the 3rd week (which remember, is when the strength phase would have just ended for the strength plus hypertrophy group), and just after the 8 weeks.

The measurements were a one-rep max test on the back squat and leg press for strength gains. And for hypertrophy, thickness of the vastus lateralis measured at 60% of the thigh length.

Results:

Increases in one-rep max on the back squat and leg press, at the 3rd week, and after the 8 weeks, was significantly greater for the strength plus hypertrophy group compared to the hypertrophy group.

These results make sense. The current evidence indicates training with relatively heavy loads and therefore lower repetitions produce the greatest increases in one-rep max strength.

The strength plus hypertrophy group spent their first 3 weeks training with 1-3 reps for both exercises.

Furthermore, the strength gains developed from this phase actually allowed them to use heavier loads during their following hypertrophy phase.

Remember, during weeks 3-8 of the study, both groups were training identically, they used 8-12 reps on the back squat and leg press, yet the strength plus hypertrophy group used heavier loads on both exercises.

Moving on, increases in vastus lateralis thickness at week 3 favored the hypertrophy group. However, by the end of the 8th week, increases in vastus lateralis thickness were greater for the strength plus hypertrophy group.

In other words, although the strength phase did not immediately produce much hypertrophy for the strength plus hypertrophy group, it seemed to have boosted the muscle growth experienced in the hypertrophy phase.

So much so that the strength plus hypertrophy group experienced greater gains than the hypertrophy group by the end of the study.

These are some really intriguing results.

What might explain them?

Why Gaining Strength First May Enhance Hypertrophy Later

Using Heavier Weights

Remember, during the last 5 weeks of the study, both groups trained identically. Despite them using 8-12 reps to failure, the strength plus hypertrophy group were able to use heavier loads, likely thanks to their prior strength phase.

The authors speculated using heavier weights in the hypertrophy phase meant the strength plus hypertrophy group experienced greater mechanical tension and hence greater muscle growth

In other words, heavier loads mean more mechanical tension and therefore more hypertrophy.

However, I’d argue this is unlikely and slightly misleading.

Let’s explore why.

Mechanical tension is currently the best-understood mechanism of muscle growth. A large component of this is active tension.

Active tension is equal to the force generated by the contractile units of a muscle. Simply put, high levels of muscle fiber recruitment and high levels of force produced by those recruited muscle fibers would mean high levels of active tension. A great stimulus for hypertrophy.

Muscles produce force progressively. When your effort is low, there are low numbers of muscle fiber recruitment and low force produced by the recruited muscle fibers. As your effort increases, increased muscle fiber recruitment and increased force produced by those recruited muscle fibers occurs.

During the last 5 weeks, both groups trained with 8-12 reps to failure. All subjects would have been exerting the same relative effort, they all used a load that enabled them to perform 8 to 12 reps to failure. So they all would have been experiencing high levels of active tension.

The fact that the strength plus hypertrophy group used heavier loads does not matter, the relative stimulus for both groups was the same.

To drive this point home, imagine we had a complete beginner and an individual with 3 years of training experience use a load they could only complete for 8 reps on the back squat.

The beginner would require a fairly light load, as they are not as strong. Whereas the trained individual would be using a much heavier load, as he would have built up some strength.

Would the trained individual grow more from doing this simply because he’s using a heavier load?

Probably not. In fact, this would likely be a much better stimulus for the untrained individual simply due to the novelty of this event for him.

Neural Adaptations Enhance Mechanical Tension?

There is another potential reason relating to mechanical tension that could help explain the study results.

As mentioned, high levels of muscle fiber recruitment and force produced by those recruited muscle fibers are a large component of mechanical tension.

Interestingly, there is some research suggesting training with heavier loads results in greater neural adaptations that enable a person to experience greater muscle fiber recruitment and/or force produced by those recruited muscle fibers.

Therefore, it’s possible the strength plus hypertrophy group, in the last 5 weeks, despite training with the same relative effort, would have been able to recruit more muscle fibers and/or produce greater force with the recruited muscle fibers thanks to the neural adaptations from their previous strength phase.

However, a limitation of this argument is some evidence suggests that neural adaptations primarily occur in the early months of a person’s training career, with little thereafter.

The subjects of the study had an average of 4 and a half years of training experience. So it’s questionable whether they would even be able to experience meaningful neural adaptations. That said, I have come across some evidence indicating even very trained individuals can still experience neural adaptations, so ultimately it’s not completely clear.

Resensitization?

A final potential reason that could explain these results relates to resensitization.

As mentioned, the subjects had an average of 4 and a half years of training experience. Unfortunately, the authors of the study did not report how the subjects trained previously. But given the popularity of using 8-12 reps, it’s possible they consistently trained with this rep range before this study.

Taking some time off from using 8-12 reps and training with 1-3 reps for a couple of weeks, as the strength plus hypertrophy group did in their strength phase, could resensitize an individual. Meaning that when they returned to using 8-12 reps in their hypertrophy phase, they were more sensitive to this rep range and gained more muscle as a result.

But this is just a hypothesis. I’m not aware of any strong evidence to support this claim.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Other Research

Moving on, it’s important to remember this is only one study.

Unfortunately, there are no other studies with an identical or near-identical design to this study.

However, there is research somewhat related that would reduce our enthusiasm about the results.

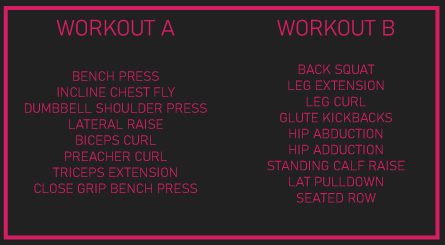

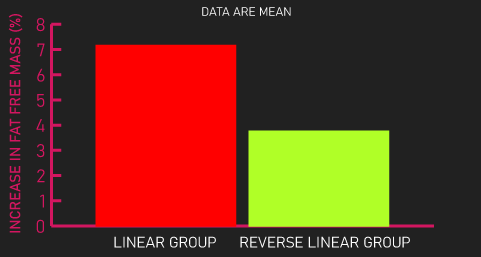

Prestes et al. split 20 women with at least 6 months of training experience into a linear or reverse linear group.

Both groups trained three times per week for 12 weeks. They alternated between workouts A and workout B. Each exercise was trained for 3 sets.

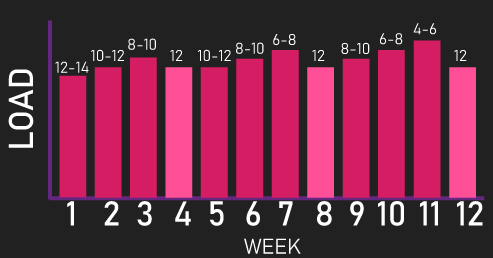

The linear group, throughout the 12 weeks, gradually progressed from using a load they could perform 12-14 reps with to a load they could perform 4-6 reps with. So they just increased the load used and decreased the number of reps performed on their exercises.

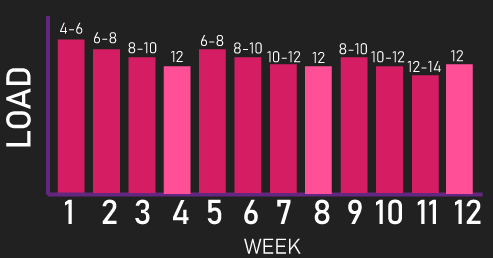

The reverse linear group did the opposite of this, throughout the 12 weeks, they gradually progressed from using a load they could perform 4-6 reps with to a load they could perform 12-14 reps with.

As a note, on weeks 4, 8, and 12, both groups performed 12 reps on their exercise sets. These weeks were recovery weeks, they also only trained twice on these weeks.

The reverse linear group is slightly comparable to the strength plus hypertrophy group in the Carvalho et al. study. In that they began with low reps and heavy weight and ended with more traditional hypertrophy training.

However, increases in fat-free mass, measured by skinfold calipers, were significantly greater for the linear group versus the reverse linear group.

Now, skinfold calipers aren’t the best measurement tool for muscle growth. MRI or ultrasound, as was used in the Carvalho et al. study, is considered much more reliable and accurate, so we should keep this in mind.

Nonetheless, this study does slightly conflict with the Carvalho et al. study.

Looking at other research, if implementing low rep training in a hypertrophy-oriented program could improve muscle growth, we would expect alternating your rep ranges to produce greater muscle growth than using only one rep range.

However, as we detailed in a previous article, the research finds no difference between alternating rep ranges or using a constant rep range for hypertrophy, at least in the short term (12 weeks or less). The Carvalho et al. study did only last 8 weeks, so it somewhat conflicts with that area of research.

Moreover, the research generally demonstrates that if you use different rep ranges in your training program, the way you organize them does not seem to impact muscle growth, at least in the short term.

A meta-analysis by Grgic et al. combined the results of studies comparing linear to daily undulating periodization.

Linear periodization, very generally, involves gradually increasing the load you use on an exercise and performing fewer reps as a result over many weeks.

Conversely, daily undulating periodization involves mixing different rep ranges into your weekly workout.

The analysis found no significant difference between the two periodization models for increasing measures of muscle growth.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, I don’t believe we have sufficient data to confidently suggest getting strong first increases hypertrophy later. Though, much of the opposing evidence to the Carvalho et al. study is indirect.

I think the idea of resensitization that we covered earlier is intriguing. If the strength plus hypertrophy group experienced greater hypertrophy because they were resensitized to the 8-12 rep range, technically, none of the indirect data we looked at could refute this.

Hopefully future research that is identical or near-identical to the study emerges. This should enable greater insight.

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.