The squat is probably arguably the most popular lower body exercise, even sometimes referred to as the king of all exercises, but is the squat enough for maximizing leg growth?

I should note that the squat here refers to the high bar back squat, as outside of powerlifting, this is probably the variation most often used. Moreover, this is the squat variation used in a lot of the research we will be evaluating throughout this article.

That said, much of the details in this article will still apply to the low bar back squat and front squat, as there are way more similarities between all these squat variations than differences.

Also, we’ll be mentioning the effect of different squats stances and depths throughout this article.

Table of Contents

Quadriceps

Let’s first figure out if the back squat is enough for maximizing quadriceps hypertrophy.

A study by Fonseca et al. gives us an interesting insight.

Protocol:

They had 49 untrained men split into five groups. Four of these groups trained while one group was a control group (they did not train).

The four training groups trained twice per week for 10 weeks.

Here is how each session looked for each training group:

As we can see, group 1 and group 3 trained the back squat only. The rep ranges used differed between the two groups. Group 1 performed 8 reps per set throughout the training period, while group 3 used a variety of rep ranges.

Groups 2 and 4 used a variety of leg exercises throughout the 10 weeks (back squat, leg press, deadlift, and lunges). These two groups also differed in the rep ranges used. Group 2 performed 8 reps per set, while group 4 used a variety of rep ranges.

The number of sets performed weekly was the same between all four training groups.

I should mention that the back squat was performed on a smith machine, and to only 90 degrees of knee flexion (participants chose their stance width). This sounds terrible, but it probably isn’t actually a big deal.

Research by Swanbeck et al. found that a program consisting of machines (which included smith machines) produced similar hypertrophy to a free weight program.

Additionally, Kubo et al. found that squatting to 140 degrees of knee flexion (deep squats) produced similar quadriceps hypertrophy to squatting with 90 degrees of knee flexion.

Measurements:

The researchers measured the cross-sectional area of the vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, rectus femoris, and vastus intermedius before and after the 10 weeks for all groups.

Results:

What the researchers found was that the groups that varied their leg exercises, so groups 2 and 4, experienced statistically significant growth of the muscles of the quadriceps (vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, recuts femoris, and vastus intermedius).

But the groups that only squatted, so groups 1 and 3, did not. Group 1 did not experience statistically significant growth of the vastus medialis and rectus femoris, while group 3 did not experience statistically significant growth of the rectus femoris.

Therefore, this study suggests that a variety of leg exercises is likely better for overall quads hypertrophy.

If you are not sold on this study because of the smith machine and 90 degrees of knee flexion, the already mentioned Kubo et al. study provides us with further valuable details.

Protocol:

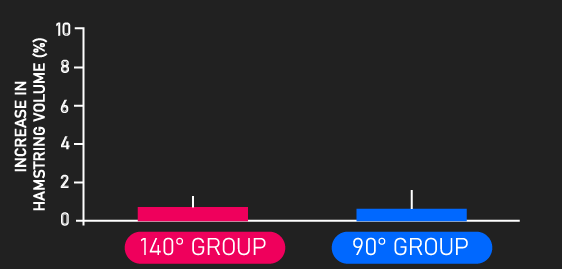

They had 17 untrained men perform either back squats with 140 degrees of knee flexion or back squats with 90 degrees of knee flexion.

Both groups used a shoulder-width stance.

They trained their respective exercise for 3 sets of 8 reps twice per week for 10 weeks.

Measurements:

The researchers measured the volume of the whole quadriceps muscle for both groups before and after the 10 weeks.

Additionally, the researchers measured the volume of each quadriceps muscle (vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, recuts femoris, and vastus intermedius) before and after the 10 weeks for both groups.

The researches did also measure a few other muscle groups, we’ll mention these later on.

Results:

As mentioned already, increases in volume for the whole quadriceps were similar between both groups. Also, changes in each quadriceps muscle were similar between both groups.

However, neither the group that squatted with 90 degrees of knee flexion or the group that squatted with 140 degrees of knee flexion experienced significant growth of the rectus femoris.

The rectus femoris:

So, from the Fonseca et al. study and the Kubo et al. study, it seems like the squat is not a particularly good exercise at growing the rectus femoris.

Anatomically, this makes sense.

The rectus femoris is the only muscle of the quadriceps that crosses both the hip and knee joints. As a result, it is involved in hip flexion and knee extension.

The other three muscles (vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius) only cross the knee joint, and are therefore only involved in knee extension.

During the bottom position of a squat, both the knees and hips must extend to complete the movement.

If the rectus femoris was to fully contract, it would partly try to flex (the opposite of extending) your hips. In other words, it would try to pull you back downwards, which is far from ideal.

Given this, the rectus femoris likely hardly contracts, explaining why it does not grow much from squatting.

As implied by the Fonseca et al. study, a variety of leg exercises may help grow the rectus femoris.

Moreover, exercises like the reverse nordic curl, and leg extension, have been documented to be great at growing the rectus femoris.

Is the Squat Enough for Maximizing Quadriceps Growth? – Conclusion

The squat does appear to be great at growing the vastus muscles (vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius) of the quadriceps.

Also, based on the Kubo et al. study, it seems squatting to 90 degrees of knee flexion is sufficient to hypertrophy these muscles.

Overall, the only paper looking at depths below 90 degrees of knee flexion for squatting is this one by Bloomquist et al.

They had one group squatting to 60 degrees of knee flexion (so very partial squats) and another group squatting to 120 degrees of knee flexion (which are around parallel squats).

The researchers measured the cross-sectional area of the quadriceps in multiple regions.

What the researchers found was that the group that squatted with 120 degrees of knee flexion experienced greater hypertrophy all measured regions of the quadriceps.

Combining this paper with the one by Kubo et al., it seems that at least 90 degrees of knee flexion is required for maximizing growth of the vastus muscles.

As for stance width, there unfortunately isn’t any longitudinal research looking at this.

However, provided your stance allows you to achieve 90 degrees or more knee flexion, I can’t think of a reason as to why there would not be sufficient growth of the vastus muscles.

Ultimately, no squat variation will be great at growing the rectus femoris. So, as mentioned, exercises such as leg extensions or reverse nordic curls (or other exercises that can hit the rectus femoris) are likely needed to maximize quadriceps hypertrophy.

Furthermore, although the squat is good at growing the vastus muscles of the quadriceps, it’s still probably sensible to include a variation of leg exercises in the long run. This can probably be useful to stimulate particular regions of the vastus muscle that may be less stimulated with the squat.

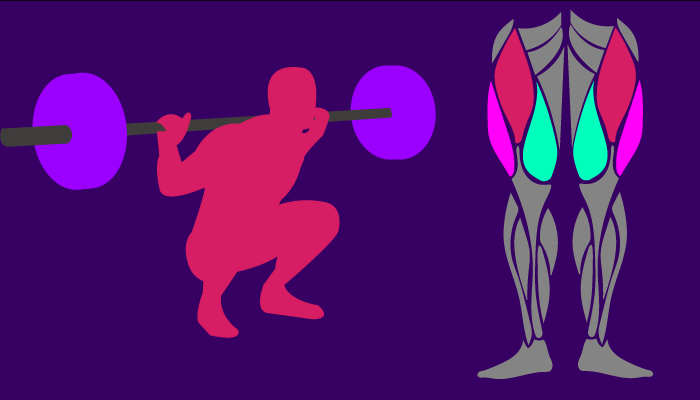

Hamstrings

One of the functions of the hamstrings is to extend the hips, and of course, in the squat, hip extension does occur.

But how much do the hamstrings contribute to hip extension in the squat?

This paper by Bryanton et al. gives us valuable insight.

They tested three different models to assess which one may be closest to reality.

Model 1 assumed that during the hip extension in the squat, the gluteus maximus and hamstrings were equally activated.

Model 2 assumed that the hamstrings did not activate until the gluteus maximus reached its maximal force-generating capacity.

Model 3 assumed the reverse of model 2, that the gluteus maximus did not activate until the hamstrings reached its maximal force-generating capacity.

What the researchers found was that model 1 and model 3 was practically impossible.

For example, regardless if the load on the back squat was 50% one-rep max or 90% one-rep max, assuming model 3 (hamstring max activation before the gluteus maximus help out), the quadriceps would have to produce more than 100% of its force-producing ability, which is impossible.

The reason for this is due to something called coactivation.

During any exercise, both the agonist and antagonist muscle contract. For example, during a biceps curl, the biceps (the agonist) contract, but the triceps (the antagonist) also contract to some degree.

This coactivation seems to just be for joint stability.

If you were to deliberately try to contract the triceps as hard as possible during a biceps curl, the biceps are going to have to work way harder to curl the weight, as both muscles have opposing functions. The triceps extend the elbow, whereas the biceps flex the elbow.

The quadriceps and hamstrings are muscles with opposing functions, the hamstrings as we have established extend the hip, but they also flex the knee. The quadriceps extend the knee (though the rectus femoris is involved in hip flexion).

Given this, in the squat, the greater hamstring contraction, the harder the quadriceps are going to have to work. This explains why model 3 is unlikely.

Model 1 (equal gluteus maximus and hamstring activation) is also unlikely. For example, at a 90% one-rep max back squat, the quadriceps would have to be producing 120% of its maximal force-producing ability (due to the hamstring coactivation), this is impossible.

We’ll discuss model 2, which is likely the most realistic model, more in the glute section.

So, from this study, the hamstrings do not seem to meaningfully contribute to the squat, simply because if they did, they would place an unrealistically high demand on the quadriceps.

Research directly assessing measurements of hamstring growth support this.

The Kubo et al. study mentioned earlier measured hamstring volume before and after the 10 weeks for both the groups.

What they found was that neither the group that squatted with 140 degrees of knee flexion or the group that squatted with 90 degrees of knee flexion experienced significant increases in hamstring volume.

The Bloomquist et al. study also mentioned earlier adds to this.

They measured the cross-sectional area of the hamstrings at multiple regions of the muscle group before and after the 12 weeks.

What the researchers found was that there were minimal increases in cross-sectional area at some regions of the hamstrings (3% or less), and actually a decrease in cross-sectional area at other regions of the hamstrings.

Is the Squat Enough for Hamstring Growth? – Conclusion

It’s clear to see that the squat is not a great movement for growing the hamstrings and is therefore not enough for hamstring growth.

Deadlift variations (particularly the Romanian deadlift or stiff-legged deadlift) and single-joint knee flexion exercises (like hamstring curls) are movements that are going to be great for growing the hamstrings.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Glutes

As promised, returning to the Bryanton et al. study, model 2 seemed the most realistic, where the gluteus maximal maxes out its contribution to hip extension before the hamstrings help out.

Assuming this model, during a 90% one-rep max back squat, the quadriceps would be producing roughly 87% of their maximal force-generating ability, which is realistic.

Therefore, the gluteus maximus does seem to play an important role in hip extension during the squat.

Research directly assessing measurements of gluteus maximus growth further supports this.

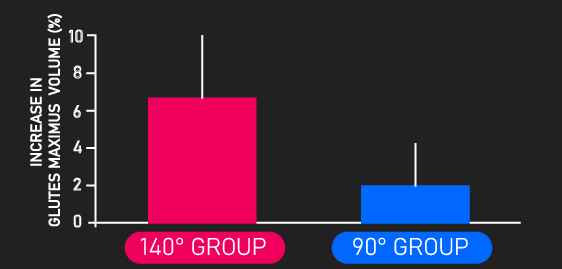

The Kubo et al. study measured gluteus maximus volume before and after the 10 weeks for both groups.

What they found was the group that squatted with 90 degrees of knee flexion experienced minimal glutes maximum growth, but the group that squatted with 140 degrees of knee flexion experienced significant gluteus maximus growth.

This is quite intriguing, with shoulder width stances (the stance width used in the study), deeper squats seem to be important for growing the gluteus maximus.

Previous biomechanical modeling research has suggested that deep squats may not be great for the gluteus maximus.

This was suggested because the internal moment arm for the gluteus maximus decreases in deeper squatting depths.

This shorter moment arm implies that the gluteus maximus would not be in an effective position to produce high amounts of force at deeper squat depths.

Despite this, as you would expect, there are numerous factors that determine how much force a muscle produces in an exercise, so internal moment arms are far from everything.

Another factor is passive tension. This is the force generated by certain structures within muscles when they are stretched.

The gluteus maximus do seem to produce passive tension when stretched (bear in mind, this is not the case for all muscles).

At deeper squats depths, the gluteus maximus are stretched more, likely allowing passive force production. This passive tension adds to the overall mechanical tension (one of the primary drivers of muscle growth). This is probably why deeper squats are favorable for gluteus maximus hypertrophy.

I should note there isn’t evidence proving passive tension to be the reason deeper squats are better for the gluteus maximus, but overall, I think it makes the most sense. I will update this article if any research comes out proving or even disproving this.

Remember, the Kubo et al. study used a shoulder-width stance.

Although there isn’t research directly assessing muscle growth with wider squat stances, there is some evidence that this stance width may be good for gluteus maximus growth.

Two papers (Paow et al. and Mccaw et al.) found the wider squat stances induced higher glutes maximus electrical activity compared to narrower stances.

Unfortunately, neither paper specified the depths that were used.

Nonetheless, most people typically with wider squat stances cannot squat deep, and generally squat to around parallel.

EMG (which measures a muscle’s electrical activity) does come with its limitations, and inferring long term adaptations for EMG can be problematic.

But regardless, I think the idea that wider stance squats can be good for glute development has some truth to it, as I think many do feel their glutes more with wider squat stances.

Is the Squat Enough for Glute Growth? – Conclusion

The current evidence does suggest that deeper squats, and perhaps wider squat stances, are good for growing the gluteus maximus.

However, I still think it is probably a good idea to have other hip extension exercises, like deadlift variations or hip thrust variations. This will probably ensure we stimulate many areas of the gluteus maximus.

It’s possible the squat may understimulate certain regions of the glutes, other hip extension exercises may help target these understimulated regions.

Moreover, some of you may have noticed I have been saying ‘gluteus maximus’ and not just glutes.

This is because the glutes not only consist of the gluteus maximus, but also the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus.

The squat primarily only targets the gluteus maximus, as the glutes maximus plays a significant role in hip extension.

The gluteus medius and gluteus minimus, on the other hand, are heavily involved in hip abduction.

Therefore, to sufficiently hypertrophy these two muscles, hip abduction exercises (like a cable hip abduction) are likely necessary.

Adductors

The adductors are probably the most underappreciated muscle groups of the lower body.

Interestingly, the squat does seem to be very good at growing the adductors.

Returning key again to the Kubo et al. study, adductor volume was measured for both groups before and after the 10 weeks.

Intriguingly, the group that squatted with 90 degrees of knee flexion experienced minimal adductor volume increases, while the group that squatted with 140 degrees of knee flexion experienced significant increases in adductor volume.

Therefore, similar to gluteus maximus growth, with shoulder width stances, deeper squats seem to be important for growing the adductors.

The adductor magnus, in particular, is likely responsible for this growth.

Biomechanical research by Vigotsky & Bryanton found that the adductor magnus is heavily involved in hip extension during the squat, especially at deeper depths. At deeper depths, it’s hip extension internal moment arm increases.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find any research on the effects of squat stance on adductor growth.

That said, similar to the gluteus maximus, I think it’s possible that wider squat stances can also be good for growing the adductor magnus.

In my experience, I definitely can feel adductor involvement with wider squat stances. Additionally, with this stance width, the adductors are somewhat stretched more than a narrower stance, meaning passive tension could enhance the overall mechanical tension.

Is the Squat Enough for Adductor Growth? – Conclusion

So, deeper squats and perhaps wider squat stances are likely good at growing the adductor magnus.

Ultimately, much of the other muscles of the adductors are probably not going to grow significantly with squat training.

The primary role of pretty much every adductor muscle is to adduct the hips.

Therefore, exercises that do this, like a cable hip adduction, are likely necessary to significantly grow the overall adductors.

Calves

Squats would involve the calves to some degree, likely just for providing balance.

However, the amount of tension produced by the muscles of the calves would be little in comparison to the amount of tension it would produce if these muscles carried out their respective functions under load.

Is the Squat Enough for Calf Growth? – Conclusion

Squats alone are not going to significantly hypertrophy the calves.

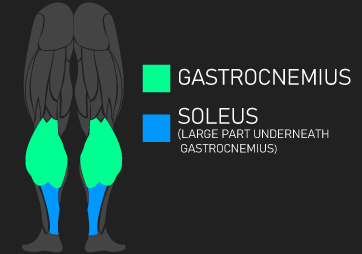

The calves consist of the gastrocnemius and soleus.

Both these muscles are heavily involved in plantar flexion. Therefore, standing and seated calf raises are exercises that would heavily recruit the calves.

As a note, seated calf raises are going to be particularly good for the soleus, while the standing calf raises are particularly good for the gastrocnemius.

Is the Squat Enough for Leg Growth? – Conclusion

The squat is without a doubt a fantastic lower body exercise. As shown throughout this article, it can significantly grow many muscles of the lower body.

But at the end of the day, the squat alone is not enough for maximizing leg growth. Other leg exercises are going to be necessary to stimulate muscles that squat may understimulate or not target at all.

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.