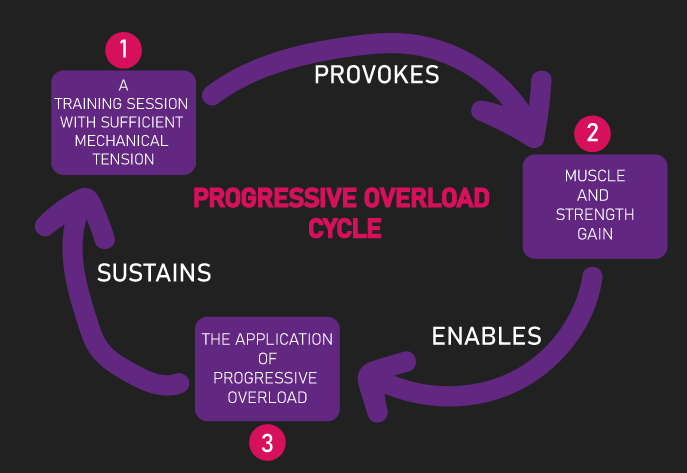

Progressive overload is necessary for making long-term hypertrophy and strength gains. Simply, it refers to progressing your training sessions in some way.

Conceptualizing progressive overload as a cycle works well. A challenging training session evokes muscle and strength gains. These gains enable you to apply progressive overload, and in turn, this application of progressive overload sustains a challenging training session.

Two popular ways to progressive overload are with all other training variables constant, either increasing the load you use or the number of repetitions you perform.

However, how do these two progressive overload forms compare to one another for long-term hypertrophy and strength?

To my knowledge, there hadn’t been any studies addressing this. But, a new study by Nobrega et al. changes this. Let’s thoroughly examine it.

New Research: Adding Load vs Reps

Subjects

The researchers did not actually conduct a new study. Rather, they used data from two of their previous studies to create this analysis. The researchers justified this as the two studies were quite comparable.

The data taken from study one involved 14 previously untrained men, while the data taken from study two involved 10 previously untrained men.

Protocol

In both studies, subjects trained the leg extension for 3 sets of repetitions to failure per session, with 2 minutes between sets, for a total of 24 sessions.

In study one, which we’ll hereafter call the subjects of this study the rep overload group, the total 24 sessions were achieved by training two times per week (on non-consecutive days) for 12 weeks.

Furthermore, this rep overload group used an 80% one-rep max load on the leg extension in the first session and did not adjust this initial load at all throughout the full study. As subjects were performing repetitions to failure every set, this would have meant this group was increasing the number of repetitions performed per set across their session. That is, they progressively overload via increasing the number of repetitions performed.

Now, I did kind of just lie. During the 6th week (corresponding to after the 12th training session), leg extension one-rep max was re-tested to return the rep overload subjects to training with a relative 80% one-rep max load. But this was only done once, and subjects kept this exact new load with no further adjustments for the remaining 6 weeks during which they would have again been simply progressively overloading via increasing repetition numbers.

In study two, which we’ll hereafter call the subjects of this study the load overload group, the total of 24 sessions was achieved by training three times per week (on non-consecutive days) for 8 weeks.

Furthermore, this load overload group adjusted their load every set and across sessions to ensure they performed roughly 9-12 repetitions to failure every set. This means they would have predominantly been progressively overloading via increasing the load used to fall within the 9-12 rep range.

As you probably noticed, although both groups ultimately performed 24 training sessions, they did not do so identically. Training frequency and total study duration differed. This is a limitation that will be returned to later.

Measurements

Nevertheless, before and after the 24 training sessions, one-rep max on the leg extension and vastus lateralis cross-sectional area at approximately 50% of the thigh bone length were measured.

Additionally, total volume load (calculated as the product of sets x repetitions x load) accumulated by the end of the 24 training sessions, as well as volume load progression across the 24 training sessions was measured.

Results

By the end of the study, total volume load, despite being numerically greater on average for the load overload group, was not statistically different between the two groups. However, progression of volume load across the 24 sessions was statistically greater for the load overload group compared to the rep overload group.

After adjusting the data based on baseline values via an analysis of covariance, increases in relative and absolute leg extension one-rep max were not statistically different between the two groups.

Note, relative increases can be thought of as percentage changes. With this data specifically, the rep overload group saw an average 31.4% increase in leg extension one-rep max, while the load overload group saw an average 38.3% increase.

Absolute increases can be thought of as measurement unit changes. With this data specifically, the rep overload group saw an average 14kg leg extension one-rep max increase, while the load overload group saw an average 15.3kg increase.

Moving forward, also after adjusting for baseline values via an analysis of covariance, increases in relative and absolute vastus lateralis cross-sectional area was statistically greater for the load overload group versus the rep overload group.

So overall, this data potentially suggests for increasing one-rep max, there may be no difference between progressively overloading via increasing load or repetition numbers. But for hypertrophy, increasing load may be superior to increasing repetition numbers.

Quite interesting, when combining both group’s data, although the researchers did not find a significant correlation between the total volume load accumulated by the end of the 24 sessions and one-rep max or vastus lateralis cross-sectional gains, a significant correlation was found for volume load progression across the 24 sessions and gains in one-rep max and vastus lateralis cross-sectional area.

As the load overload group saw greater progressions in volume load across the 24 sessions, this led the authors to suggest this greater volume load progression may explain the greater hypertrophy experienced for this group.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Limitations With the Analysis

Having detailed all of this, there are some extremely important limitations and counterevidence. Let’s explore this to derive some more informed conclusions.

Firstly, recall this study combined and analyzed two independent studies together, and as such it was not a randomized controlled study.

They Likely Trained Suboptimally for Strength

Secondly, it’s interesting that both groups saw similar one-rep max gains. Yet, it’s more than likely all subjects trained suboptimally for strength. Both groups trained with loads that enabled 8 or more repetitions per set. Yet, the current evidence indicates training with loads that result in you performing 5 or fewer maximum repetitions is probably more favorable for one-rep max gains. For example, Schoenfeld et al. found with the back squat and bench press, adjusting loads every set and across sessions to maintain 2-4 repetitions to failure produced larger bench press and back squat one-rep max gains versus adjusting loads every set and across sessions to maintain 8-12 repetitions to failure.

One question arising from this is what if both groups simply started with a 2-4 rep max load, with one group progressively overloading via adding reps from hereafter, and another group simply adjusting loads every set and across sessions to maintain 2-4 repetitions, would both still be similarly effective for promoting one-rep max gains? Hopefully future research explores this.

Training Frequency and Study Durations Differed

Thirdly, we know that although both groups ultimately performed 24 training sessions, they did not do so identically. The rep overload group performed 3 leg extension sets 2x per week for 12 weeks, meaning they performed 6 leg extension sets per week. The load overload group performed 3 leg extension sets 3x per week for 8 weeks, meaning they performed 9 weekly leg extension sets.

However, using other data, it’s actually difficult to say this is a true limitation.

The evidence indicates when performing 10 or fewer weekly sets for a muscle or exercise (as both groups were doing), training frequency does not seem to matter for strength or hypertrophy. That is, whether you perform these 10 or fewer weekly sets for a muscle all in one session, or across two or more days does not really matter. So neither training two or three times per week are inherently superior to each other in this regard.

However, the load overload group did perform 9 weekly sets on the leg extension, while the rep overload group only performed 6 weekly leg extension sets. Based on the current data, it’s probably likely that on average, performing 9 weekly sets for an exercise or muscle is better than fewer for hypertrophy and strength. Thus, on a per week basis, the load overload group was likely gaining more. However, remember the load overload group only trained for 8 weeks to reach the 24 sessions, while the rep overload group trained for 12 weeks to reach the 24 total sessions, thus these study’s duration differences likely cancel out the per week growth differences. Ultimately probably meaning that use of different training frequencies may not be a major problem.

Having said all of this, it’s important to note muscle and strength gain are not constant. Generally, each week an individual would incrementally experience fewer gains. This throws another curveball and makes the comparisons pretty confusing.

Therefore, overall, it’s truly difficult to comment on how these difference in training frequency and study durations between the two groups impacts the results. It would have been much better to have controlled these variables.

Small Sample Size

The fourth limitation is that the sample sizes were small, as is most commonly the case with resistance training studies. 14 subjects were in the rep overload group, and 10 subjects in the load overload group.

Small sample sizes increase the chance of errors. Let me explain.

Different individuals, despite training with exactly the same training variables, can have very different outcomes.

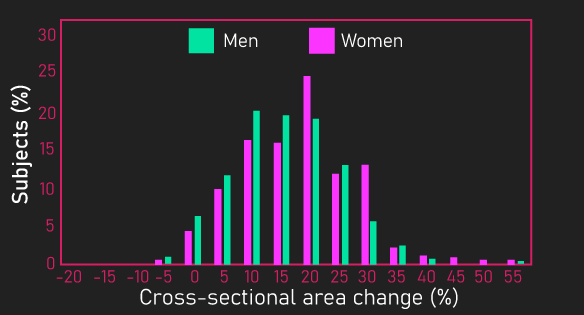

For example, Hubal et al. had 243 men and 342 women train preacher and concentration curls for 12 weeks. Below is a graph illustrating how the subject’s biceps cross-sectional area was impacted by training.

Most individuals tended to experience a 10-30% increase in biceps cross-sectional area, but there were individuals experiencing well above this as well as individuals experiencing gains well below this.

Here’s the thing, with small sample sizes, your chance of selecting subjects that vary widely in response abilities is increased.

Expanding on this, we know the Nobrega data found the load overload group experienced higher vastus lateralis cross sectional area gains versus the rep overload group. But it’s entirely possible, due to the small sample sizes, the load overload group consisted of subjects with an average better muscle building ability versus the rep overload group. Thus, this would explain why the load overload group saw greater vastus lateralis gains, and not necessarily that overloading via load increases is superior.

Measurement and Variables

The fifth limitation relates to the measures and variables used in the study.

Vastus lateralis thickness (at roughly 50% of the thigh bone length) was measured). But what about gains at other regions of the vastus lateralis, and even gains at other regions of the quadriceps muscles. For instance, other data indicates leg extension training (the exercise trained by subjects) heavily grows the rectus femoris part of the quadriceps. Thus, what did growth look like in this muscle?

Only the leg extension was trained, what about other exercises?

The subjects were also previously untrained individuals, do these results apply to trained individuals?

Potential Counterevidence?

Finally, although I would not consider this a limitation, rather potential counterevidence, it’s quite difficult to explain the finding of the load overload group experiencing greater vastus lateralis cross-sectional area gains compared to the rep overload group when considering other data.

There’s quite a bit of data indicating loads between 30% and 80% one-rep max, so long as repetitions are performed very close or to failure, produce similar muscle hypertrophy.

One of the reasons for this is likely because when performing repetitions very close or to failure within this loading zone, you’re going to be evoking quite high mechanical tension levels. More precisely, muscle fiber recruitment and force production by the individual muscle fibers is going to be quite high (these are two parts of mechanical tension). The reason this matters is because mechanical tension is currently the best categorized stimulus for hypertrophy.

If you start with a given loading, let’s say 80% one-rep max, and progress via increasing your repetition numbers over sessions, the relative load you’re training with will technically decrease. But so long as you’re performing repetitions to or very close to failure, and that relative loading remains in the 30 to 80% one-rep max zone, you would presumably think hypertrophy should more or less be optimally stimulated.

If you start with a given load that has you perform a certain number of repetitions, and you opt to try and maintain the precise relative loading (and subsequently rep range) every session via increasing the load, provided you’re performing repetitions to or very close to failure, and the relative loading you’re trying to maintain is within the 30 to 80% zone, you would also presumably think hypertrophy should more or less be optimally stimulated.

My point with all this is there currently does not appear to be any rationale as to why progressively overloading through increasing load may be superior to progressively overloading via increasing repetition numbers.

However, recall the authors of the study proposed that the greater volume load progression achieved by the load overload group, compared to the rep overload group, might explain the greater hypertrophy.

Put another way, greater volume load progression week to week might mean more hypertrophy. Indeed, the researchers, when combining the data for all subjects, did note a correlation between volume load progression and vastus lateralis cross-sectional gains.

However, the problem here is that not only does correlation not indicate causation, but other areas of the research suggest volume load progression is completely dissociated from hypertrophy.

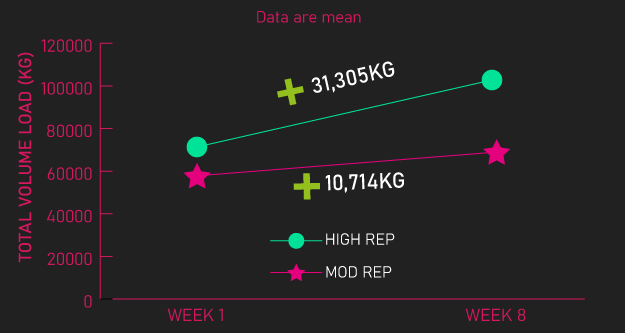

Schoenfeld et al. had a group of men with 1.5-9 years of training experience perform a range of exercises each for 3 sets, 3 times per week for 8 weeks.

One group of subjects (a high rep group) performed each exercise with 25-35 repetitions to failure each set.

Another group of subjects (a moderate rep group) performed each exercise with 8-12 repetitions to failure each set.

Note, both groups adjusted loads every set and across sessions to ensure subjects kept training to failure within their respective rep range.

Across the 8 weeks, volume load progression was greater for the subjects training with 25-35 reps, versus the subjects training with 8-12 reps.

If volume load progression itself was truly important for hypertrophy, training with 25-35 reps should be superior to training with 8-12 reps. Yet, as we’ve mentioned already, loads between 30% and 80% one-rep max (which would include the aforementioned rep ranges) are likely comparably effective for hypertrophy when repetitions are performed very close or to failure.

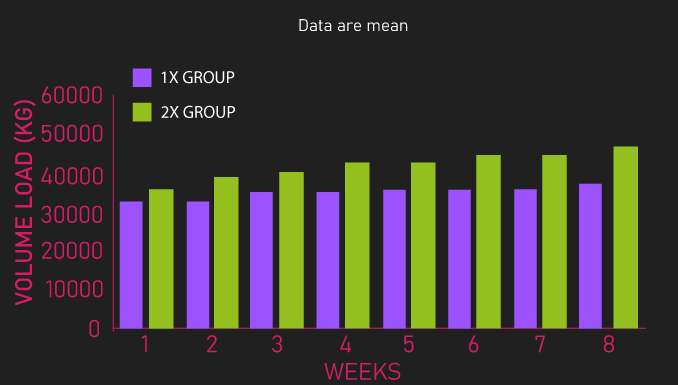

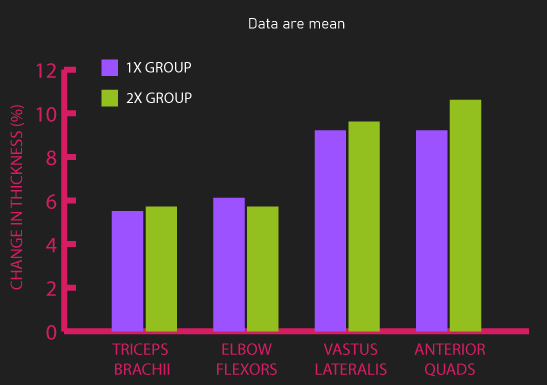

Another study by Brigatto et al. either had men with 2-8 years of training experience target a specific muscle all in one session (the 1x group), or across 2 sessions a week (the 2x group). All other training variables (including weekly set numbers, exercise selection, and rest interval duration between sets) were the same between both groups.

Across 8 weeks of training, volume load progression on the exercises was greater for the 2x group versus the 1x group.

Yet, increases in thickness of various muscles were similar between both groups, again indicating volume load progression may not be predictive of hypertrophy.

Two studies by Souza Junior et al., which we’ve thoroughly evaluated in a previous article, fundamentally seemed to compare progressively overloading via decreasing rest interval duration between sets to increasing load. Despite volume load progression across 8 training weeks being larger for the subjects increasing load, increases in arm and thigh cross-sectional area were similar between the subjects decreasing rest interval durations between sets and the subjects increasing load.

Finally, as just mentioned, these two Souza Junior et al. studies indicated that as a form of progressive overload, decreasing rest interval durations between sets was as effective as increasing load. Of course, these studies did have their own limitations, which we’ve addressed in a previous article. However, If we took these findings literally, and combined it with the findings of this Nobrega study (that is, we’ll literally assume increasing load is better than increasing repetition numbers for hypertrophy), using some illegal maths, we would come to the conclusion that as decreasing rest intervals is similarly effective to increasing load for hypertrophy, but increasing load is better than increasing repetition numbers for hypertrophy, decreasing rest interval durations between sets would be better than increase repetition numbers for hypertrophy. I’m sure many would agree this is an odd conclusion. The only way to truly assess the validity of this would be to have further studies comparing these different forms of progressive overload.

Conclusion

In summary, although this analysis by Nobrega et al. was highly interesting, numerous limitations and potential counter evidence exist. As such, I believe we can be nowhere close to definitively concluding that increasing load is better than increasing repetition numbers for hypertrophy, or that both methods are similarly effective for strength.

Further research is unquestionably required.

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.