With the same exercise, performing it one way can produce drastically more muscle hypertrophy than performing it another way.

This is because the current data demonstrate that the length you train a muscle at can profoundly influence the amount of hypertrophy produced.

In this article, we’ll explore this current data, discuss some notable considerations, and then figure out how you could leverage this literature to enhance hypertrophy with your exercises.

Allow us to first examine a recent study by Sato et al., demonstrating how biceps hypertrophy can powerfully be enhanced by training at a certain muscle length.

Table of Contents

Part 1: Sato et al.

Subjects

Sato et al. recruited 32 individuals who had not been training at least in the last 6 months and assigned them to either a long length, short length, or control group.

We won’t mention the control group from hereafter. They did not train and expectedly made no gains.

Protocol

Both the long length and short length groups trained the dumbbell preacher curl twice per week for 5 weeks.

The long length group trained the exercise from 0 to 50 degrees of elbow flexion. This trained the biceps at a long length. That is, a stretched position. The short length group trained the exercise from 80 to 130 degrees of elbow flexion. This trained the biceps at a short length. That is, a more contracted position.

Now, many of you are probably thinking what about a full range of motion group? Unfortunately, the researchers did not have a full range of motion group. But we’ll return to this point soon.

Both groups, each session, performed 3 sets of 10 repetitions with 3 minutes of rest between sets.

What about loads? What loads did the subjects train with?

The way the researchers prescribed loads was slightly unique and not typical.

For the long length group, before the study, they measured the amount of maximal isometric force they could produce at 50 degrees of elbow flexion.

This value was then used to determine what dumbbell load they trained with, and it varied throughout the total 10 training sessions they completed.

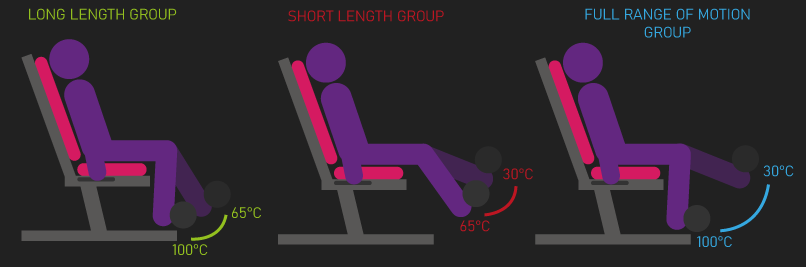

In the first session, the long length group trained with a dumbbell load equating to 30% of their maximal isometric force at 50 degrees of elbow flexion. This progressed to 100% by the 10th and final session.

For the short length group, opposingly, the researchers measured the amount of maximal isometric force they could produce at 90 degrees of elbow flexion before the study.

This value was then used to determine what dumbbell load they trained with. Like the long length group, they trained with 30% of the maximal isometric force in the first session, and this progressed to 100% by the 10th and final training session.

Measurerments

Before and after the study, elbow flexor thickness was measured at 50%, 60%, and 70% of the approximate upper arm length.

Additionally, the average of these three locations was taken to obtain a single average elbow flexor thickness measurement.

I should note the elbow flexors in this case not only includes the biceps muscle, but also the brachialis.

Results

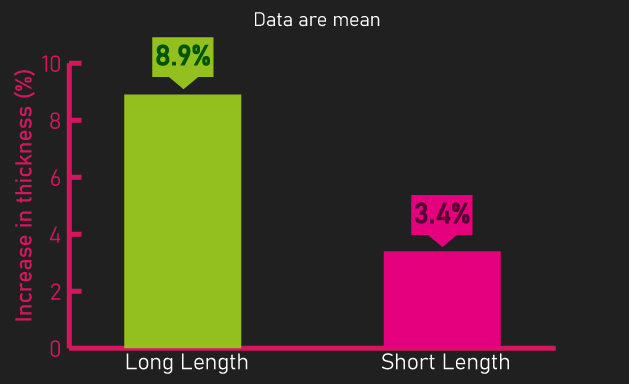

What the researchers found was that increases in elbow flexor thickness at 50% and 60% of the upper arm length were similar between both groups. But, increases in elbow flexor thickness at 70% of the upper arm length were greater for the long length group.

Averaging these three elbow flexor thickness regions, the long length group saw significantly greater increases versus the short length group. Gains were approximately 3x greater for the long length group.

Part 2: What about Full ROM?

Now, a question everyone probably has is how would have this partial range of motion at long lengths compared to a full range of motion?

We can’t be certain simply as the Sato et al. study never had a full range of motion group. But, does any other research help us out?

Most of the studies looking at a full range of motion have compared it to only a partial range of motion at short muscle lengths, and they have found a full range of motion is superior for overall hypertrophy.

However, notice how I said most of the studies. There is indeed one study by Pedrosa et al. evaluating how a partial range of motion at long muscle lengths compares to a full range of motion, and it suggests a partial range of motion at long muscle lengths could be superior.

This group of researchers had previously untrained women train the leg extension with one of four different programs.

A long length group trained the leg extension from 100 to 65 degrees of knee flexion, which trains the quadriceps at a long length. A short length group trained the leg extension from 65 to 30 degrees of knee flexion, which trains the quadriceps at a short length. A full range of motion group trained the leg extension from 100 to 30 degrees of knee flexion.

Finally, a varied group alternated back and forth between training the long length and short length leg extension every session.

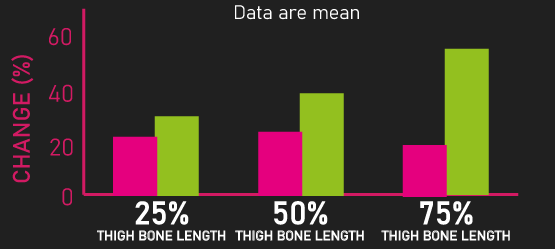

Before and after the study, cross-sectional area of the vastus lateralis and rectus femoris was each measured at 40%, 50%, 60%, and 70% of the approximate thigh bone length.

Overall, the long length group saw the greatest gains, with the varied group being a close second.

More precisely, at 40% of the thigh bone length, increases in rectus femoris and vastus lateralis cross-sectional area were statistically similar between all groups.

But at 50% of the thigh bone length, increases for the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis were similar between the long length and varied group but both greater than the other two groups.

At 60% of the thigh bone length, increases for the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis were similar between the long length and varied group but greater than the two other groups.

Finally, at 70% of the thigh bone length, increases for the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis were greatest for the long length group compared to all other groups.

Therefore, this study qualifies as evidence that a partial range of motion at long muscle lengths might be more powerful than a full range of motion for stimulating muscle hypertrophy.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Part 3: Other data

I think it’s worth the reader being aware there is a fair bit of other evidence demonstrating that training a muscle at a long length evokes more hypertrophy than short lengths.

An analysis by Oranchuk et al. combined the results of 9 studies looking at how hypertrophy is impacted by training isometrically at long muscle lengths or short muscle lengths.

Overall, hypertrophy was greater when training at long muscle lengths.

Another study by McMahon et al. had a long length group train leg extensions from 90 to 40 degrees of knee flexion, and a short length group training leg extensions from 50 to 0 degrees of knee flexion.

Increases in cross-sectional area of the vastus lateralis at 25% and 50% of the approximate thigh bone length were not statistically different between the long and short length groups. But, increases in cross-sectional area of the vastus lateralis at 75% of the approximate thigh bone length were significantly greater for the long length group.

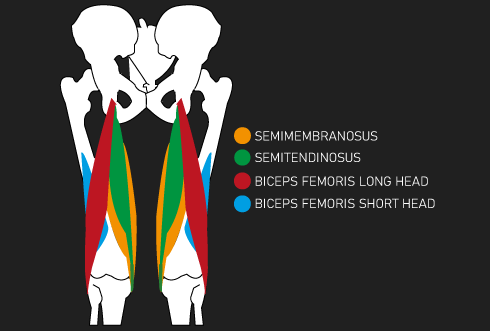

Finally, Maoe et al. either had subjects train the lying leg curl or seated leg curl, with both executed from 0 to 90 degrees of knee flexion (which is more or less a full range of motion for both movements).

Now, as 3 of the 4 hamstring muscles (biceps femoris long head, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus) cross both the hip and knee joints, seated leg curls (due to the hip flexion it involves) would stretch these muscles much more than lying leg curls.

The other hamstring muscles (the biceps femoris short head) only cross the knee joint and thus is likely at a similar length between the lying and seated leg curls.

It was found that volume increases in the 3 hamstring muscles that cross the hip and knee joint were significantly greater after training the seated leg curl versus the lying leg curls.

The other hamstring muscle, the biceps femoris short head, experienced similar volume increases between training the lying and seated leg curls.

This study demonstrates that even with the same overall joint range of motion, selecting an exercise that can achieve a greater stretch of a muscle can evoke significantly more muscle hypertrophy.

Part 4: Regional Hypertrophy Differences

Before discussing some considerations of the data we’ve overviewed, and then the potential takeaways, it’s worth noting much of the data we’ve overviewed shows there are notable differences in regional hypertrophy between training at long and short muscle lengths.

The studies by Sato, Pedrosa, and McMahon indicate that growth of the upper or middle portions of a muscle is fairly similar between training at a long and short length, or slightly greater when training at a long length.

However, in the more lower regions of a muscle, training at a long length produces substantially more growth than training at a short length.

Part 5: Some Considerations

It’s worth noting in all the data we’ve overviewed assessing differences between training at a long, short, or with a full range of motion, the biceps, quadriceps, and hamstring muscles were evaluated.

I think it’s likely for muscles belonging to the arms and legs, and perhaps even the chest, training at a long length would produce significantly more hypertrophy than training at a short length.

However, for some muscles, such as some back muscles, and the trap muscles, not only is it probably difficult to find suitable exercises to train these muscles at a long length, but would training at a long length even be superior for these muscles?

For example, I have a hard time believing partial rowing of any kind in the lower position would produce more growth than full range of motion rows where you can contract and squeeze the back muscles. Moreover, would partial shrugs in the lower portion produce more hypertrophy than full range of motion shrugs where you can squeeze the traps.

The point here is I feel it’s completely possible some muscles, like the back and traps, might not necessarily benefit from being trained at a long length. But, I could completely be wrong. Hopefully future research examines this further.

Part 6: Takeaway

For many muscles, specifically those belonging to the limbs and probably the chest as well, I think it’s very likely training at long muscle lengths is going to be superior for overall hypertrophy compared to training at short muscle lengths.

Furthermore, it’s quite possible using a partial range of motion at long lengths produces more hypertrophy overall than training with a full range of motion. But, this conclusion is only derived from a single study.

As a result, I don’t believe we can confidently conclude training a partial range of motion at long lengths is 100% of the time going to be more hypertrophic than a full range of motion. More research is going to need to be conducted in this area.

Based on your interpretations of the data, you might actually wish to experiment with partial range of motion at long lengths. It’s clear to see this type of partial range of motion will produce robust hypertrophy.

At the very least though, with many of your exercises that train the muscles of the limb (and perhaps the chest muscle too), focusing on exercises and ranges of motions that can meaningfully load the muscle in a stretched position is likely a great idea.

For example, as per the Maeo et al. study overviewed earlier, seated leg curls are going to be better than lying leg curls.

With squatting exercises, trying to go as deep as you comfortably can is likely going to be better for overall lower body hypertrophy.

With deadlift exercises, if you’d like to achieve the most hamstring growth from them, ensuring you do not excessively bend the knees and choosing a variation that allows you to achieve significant hip flexion (such as stiff-legged deadlifts) is likely a good idea.

Of course, as noted, I think it’s completely possible some muscles (like some of the back muscles and maybe the traps) might not necessarily grow more with training at long lengths. But again, future research is needed to falsify or verify this.

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.