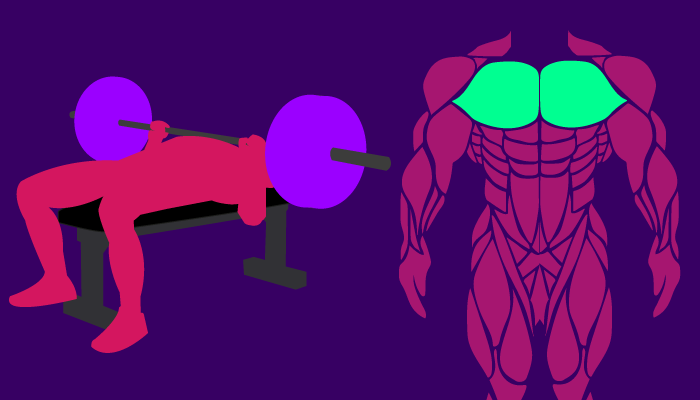

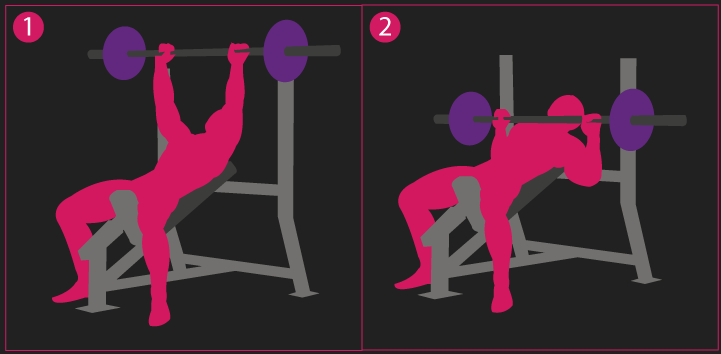

The barbell bench press is probably the most popular upper body exercise. In this exercise, the muscles of the chest are considered a prime mover.

In a previous article, we explored an interesting study assessing how well the bench press does at developing the triceps.

In this article, we’ll be thoroughly evaluating the current research on the barbell bench press and chest growth. More specifically, we aim to find out if the barbell bench press alone is enough for chest growth.

Table of Contents

Pectoralis Major

First of all, it’s useful to establish what we mean by the muscles of the chest (anatomy) as well as what bodily movements best recruit this musculature (function).

From there, we can analyze the movements that occur in the barbell bench press, with the hope of concluding if this exercise is indeed ideal for engaging the chest.

Broadly, muscles that connect the chest (thorax) to the shoulder and upper arm are the chest muscles. This includes the pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, subclavius muscle, and serratus anterior.

From this point forward, for two reasons, we will only be discussing the pectoralis major. Firstly, this muscle covers the large bulk of the chest. Secondly, all the research we will evaluate has specifically assessed this muscle.

Besides, I think when most people discuss or picture the chest muscles, they are generally referring to the pectoralis major.

Anatomy

The pectoralis major, as is the case with every single muscle in the body, creates movement via its attachments to bones.

When a muscle dynamically contracts, the attachments remaining stationary are termed the origin, whereas attachments that move are called the insertion.

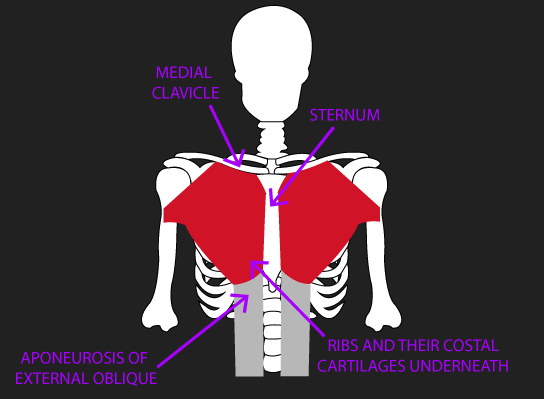

The pectoralis major has a range of origins. The location of these origins ranges from the medial clavicle, sternum, ribs, the cartilage of those ribs (costal cartilage), and the aponeurosis of the external oblique.

All the muscle fibers of the pectoralis major, despite having varying origins, all insert into generally the same location, the lateral side of the upper arm (technically termed the lateral lip of the bicipital groove of the humerus), which is the insertion.

It’s common to split up a muscle based on muscle fibers sharing the same origin location.

Unfortunately, with the pectoralis major, there is no universal agreement on these divisions.

Some consider the pectoralis major to have three different heads, a clavicular head (consisting of fibers originating from the medial clavicle), sternal head (consisting of fibers originating from the sternum), and a costal head (consisting of fibers originating from the ribs, their costal cartilages, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique).

I should also note the clavicular head is also often called the upper chest, the sternal head the middle chest, and the costal head the lower chest.

However, others consider the pectoralis major to have only two heads, a clavicular head (consisting of fibers originating from the medial clavicle) and a sternocostal head (consisting of fibers originating from the sternum, ribs, costal cartilages, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique).

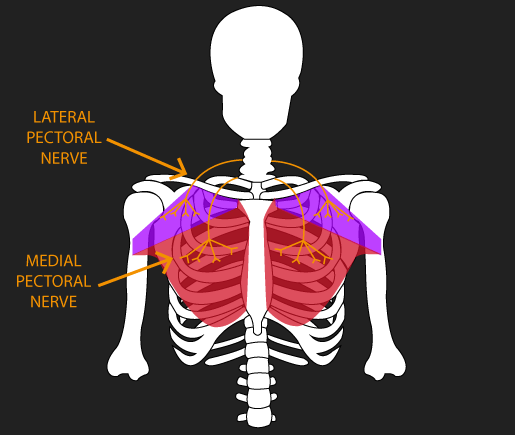

In further support of this division, the clavicular and sternocostal head have distinct innervations. Remember, the reason muscle fibers contract is because they receive signals from nerve cells.

The clavicular head fibers generally receive signals from the lateral pectoral nerve. The sternocostal head generally receives signals from the medial pectoral nerve.

As we’ll see when evaluating the research shortly, different researchers use different divisions of the pectoralis major. Some discuss three heads (clavicular head, sternal head, and costal head) and others two heads (clavicular head and sternocostal head).

Function

Now we’ve established some anatomical details about the pectoralis major, let us look at what movements engage the pectoralis major.

Research assessing the length of the pectoralis major’s internal moment arm during various movements can help us.

The internal moment arm is the perpendicular distance between a muscle’s line of action and the joint it is moving.

If this sounds confusing, the biceps brachii muscle gives us a clear illustration of this. A muscle’s line of action is a straight line from its origin to its insertion (shown in the image below). The joint the biceps brachii moves is the elbow.

Now, we simply draw a perpendicular line between these. The distance of this perpendicular line is the internal moment arm for the biceps brachii at this exact position.

As the arm curls up or down, its internal moment arm will change.

In essence, the longer the moment arm during any given point in a movement, the more leverage the muscle has on a joint, meaning it is in a position to produce high amounts of force.

When assessing the internal moment arms of numerous muscles during a given movement, the muscles that display the longest moment arm throughout the motion are likely going to be heavily recruited.

The joint the pectoralis major moves is the shoulder. Let us evaluate the research comparing the internal moment arm of the pectoralis major to other muscles during shoulder movements.

During horizontal flexion, the anterior deltoid and pectoralis major display the largest internal moment arms. From approximately 0 to 10 degrees of horizontal flexion, the anterior deltoid has slightly better leverage (a longer internal moment arm) than the pectoralis major. However, from 10 degrees all the way up to 140 degrees of horizontal flexion, the pectoralis major has the greatest leverage.

During shoulder flexion, the pectoralis major, anterior deltoid, middle deltoid, and supraspinatus display the largest internal moment arms. Interestingly, during this motion, there likely are meaningful differences between different regions of the pectoralis major. The clavicular head has substantially greater leverage than the sternal head throughout shoulder flexion. Furthermore, the costal head actually has some leverage for shoulder extension, meaning it is not involved in shoulder flexion at all, rather the reverse of this.

It’s important to note that despite the clavicular head having the greatest leverage during shoulder flexion of all the pectoralis major, its leverage is still less than the anterior deltoid. So although the clavicular head would likely be activated to a good degree during shoulder flexion, the anterior deltoid would probably experience greater activation.

Shoulder adduction is another movement the pectoralis major is likely involved in, along with the latissimus dorsi, teres major, and subscapularis. But, similar to shoulder flexion, there does appear to be meaningful differences between regions of the pectoralis major. The sternal and costal heads both display somewhat comparable moderate internal moment arms throughout shoulder adduction. Conversely, the clavicular head actually has a small shoulder abduction moment arm from 40 degrees of abduction onwards.

However, the latissimus dorsi and teres major appear to have longer internal moment arms than the sternal and costal heads of the pectoralis major throughout shoulder adduction. Additionally, the anterior deltoid and especially the lateral deltoid have a much longer moment arm during shoulder abduction compared to the clavicular head. Therefore, shoulder adduction or shoulder abduction exercises are likely not ideal for the pectoralis major.

Finally, the pectoralis major appears to be highly involved in internal rotation. This particular finding comes from electromyography research. Electromyography is used to measure the electric activity of a muscle. This linked study evaluated the activity of numerous muscles that move the shoulder during a variety of shoulder movements. They found the pectoralis major displayed the greatest electric activity during internal rotation.

Analyzing the Movements in the Bench Press

To sum up the previous section, the pectoralis major are involved in horizontal flexion, shoulder flexion (except for the costal head which is involved in shoulder extension), shoulder adduction (except for the clavicular head which is involved in shoulder abduction), and internal rotation.

Do any of these motions occur during the bench press?

It turns out that all of these movements, but shoulder adduction or abduction, occurs to a good degree in the bench press.

Recall that we mentioned shoulder adduction is primarily carried out by the latissimus dorsi and teres major. Also, shoulder abduction would be primarily carried out by the anterior and lateral deltoid. Therefore, the absence of these movements during the bench press isn’t really an issue with regards to pectoralis major development.

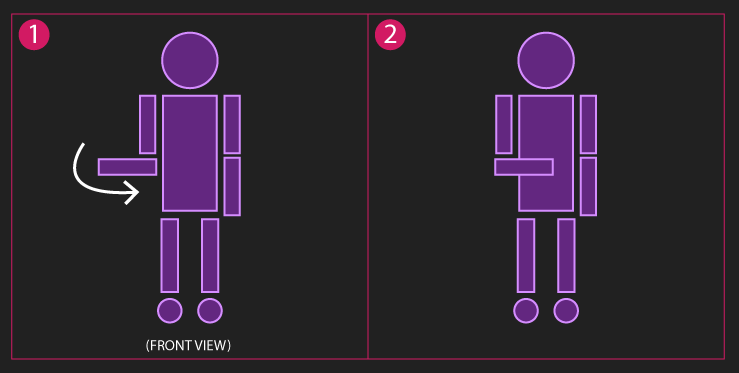

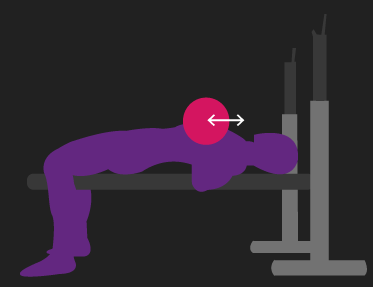

Horizontal Flexion

Horizontal flexion can be described as moving your arm towards the midline of your body while your arms are parallel to the ground..

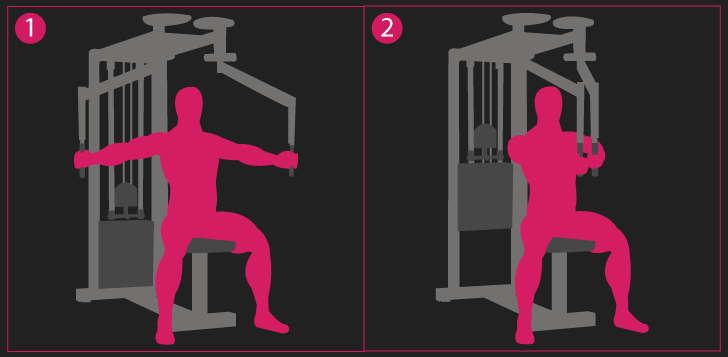

An exercise that perfectly depicts this motion is a seated chest fly.

During the bench press, the degree of horizontal flexion is determined by the grip width used. As grip width remains unchanged throughout the execution of a barbell bench press, so does the degree of horizontal flexion.

For instance, if you performed the exercise with your wrists directly under your elbows and shoulders before the descent phase (a shoulder-width grip), 90 degrees of horizontal flexion is used.

Kuechle et al. suggests the pectoralis major has its longest moment arm at roughly 40 to 50 degrees of horizontal flexion.

Generally, this would equate to a relatively wide grip. Roughly speaking, this probably equals anywhere from a 1.5x to 2x shoulder-width grip for most people. Theoretically, this grip width may be optimal for pectoralis major development.

Shoulder Flexion

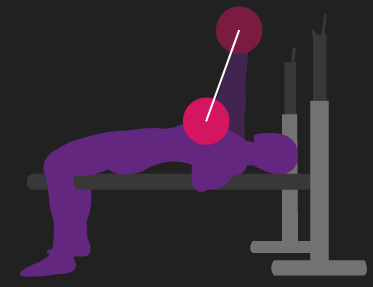

Viewing the normal barbell bench press from the side, a correct descent (eccentric) phase results in a diagonal-ish line.

Once the barbell is at its lowest position (normally around the mid-chest to the lower-chest area for most people) the distance between your shoulders and the barbell indicates how much shoulder flexion must occur during the ascent (concentric) phase.

Simply put, the longer this distance, the more shoulder flexion required.

Remember, the anterior deltoid does have a longer internal moment arm throughout shoulder flexion than the pectoralis major. Therefore, for pectoralis major development we would not be aiming to maximize the degree of shoulder flexion.

As noted, descending the barbell to the mid-chest or lower-chest region works well for most people.

Internal Rotation

When initiating the ascent phase of the bench press, aiming to flare your elbows out is likely advantageous. Firstly, doing this will likely allow the pectoralis major to produce more force through a more efficient pull on the upper arm. Secondly, during a barbell bench press, the triceps produce lateral force (force directed towards either side). Flaring your elbows allows greater lateral force, and therefore a stronger triceps contraction.

For most people, flaring your elbows will naturally cause internal rotation during the ascent phase of the barbell bench press.

In summary, the main functions of the pectoralis major do indeed seem to occur to some capacity in the barbell bench press, indicating the barbell bench press may be an excellent movement for developing this muscle.

Moving on from this anatomical and functional discussion, let us now evaluate research assessing just how well the barbell bench press does at growing the pectoralis major.

Research on the Bench Press & Pectoralis Major Hypertrophy

Correlation Between Bench Press Strength and Pectoralis Major Size

Starting things off, a study by Akagi et al. aimed to determine the relationship between pectoralis major size and bench press one-rep max.

18 men with at least one year of training experience had their smith bench press one-rep max measured as well the cross-sectional area of their pectoralis major at multiple regions. The largest cross-sectional area value obtained for an individual was used for analysis.

The researchers found a significant correlation between smith machine bench press one-rep max and pectoralis major cross-sectional area. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was 0.86 (1 is a perfect linear relationship, while 0 is no relationship whatsoever).

Put differently, the greater an individual’s smith machine bench press one-rep max, the bigger their pectoralis major.

Now, this study used the smith machine bench press. But generally, the stronger you are on the barbell bench press, the stronger you would likely be on the smith machine bench press.

Therefore, this study would imply that the stronger you get on the barbell bench press, the greater hypertrophy the pectoralis major would experience.

However, this was only a correlation study. It fails to tell us if training the bench press as your only chest exercise would be sufficient to linearly increase pectoralis major size. Furthermore, this study does not inform us of how well the bench press does at developing different regions of the pectoralis major.

For these, we would need to look at research assessing pectoralis major growth at certain regions before and after a period of training the bench press exclusively (i.e. longitudinal research).

Longitudinal Research

Brandao et al. had a group of untrained men train the barbell bench press for 3 to 5 sets to failure (the point at which no more repetitions can be performed) with an 80% one-rep max load and three minutes of rest between sets, twice per week for 10 weeks.

A 2x shoulder-width was used on the barbell.

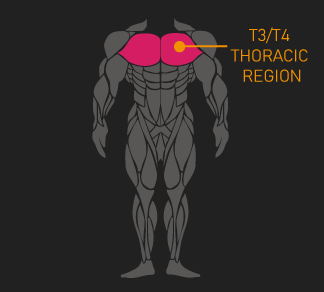

The cross-sectional area of the pectoralis major, which was measured at the T3/T4 thoracic region, increased by 9.1% on average.

A 9.1% increase in cross-sectional area in 10 weeks of training would equate to an average 0.13% cross-sectional area increase per day (9.1% divided by 70 days).

Is this 0.13% cross-sectional area increase per day a lot or hardly anything?

A review paper by Wernbom et al. can help us here.

Through assessing numerous studies, they measured the average increase in cross-sectional area per day for the quadriceps and elbow flexors muscle after a period of training.

Based on the collection of these numerous studies, the quadriceps, on average, experienced a 0.11% increase in cross-sectional area per day when trained with roughly 6 sets per session, three times per week for 11 weeks.

The elbow flexors, on average, experienced a 0.20% increase in cross-sectional area per day when trained with roughly 5 sets per session, three times per week for 12 weeks.

I should also note these numbers are averaged from studies that mainly involved untrained subjects.

So, as we can see, the barbell bench press in the Brandao et al. study did not do a terrible job. The 0.13% increase in pectoralis major cross-sectional area per day was above the 0.11% increase for the quadriceps but below the 0.20% increase for the elbow flexors.

Interestingly, Wernbom et al. suggested the reason the elbow flexors experience a greater rate of hypertrophy versus the quadriceps was because the quadriceps are generally involved more in day-to-day tasks, meaning they are somewhat trained, thus slightly limiting its capacity to hypertrophy further.

The pectoralis major is probably more similar to the elbow flexors in that they aren’t as heavily used day-to-day compared to the quadriceps.

Considering this, one could argue the Brandao et al. results were suboptimal, given the 0.13% increase in cross-sectional area was less than the 0.20% increase in elbow flexor cross-sectional area.

At the same time though, it’s important to note the 0.20% increase in elbow flexor cross-sectional area per day was from studies that averaged 6 sets per session and three sessions per week for the muscle group.

The Brandao et al. study averaged around 4 sets on the bench press only twice per week.

These differences do limit our ability to fairly compare the two sets of results.

Nonetheless, let’s move on to the other longitudinal research.

Yasuda et al. had a group of untrained men perform the barbell bench press for 3 sets of 10 reps with a 75% one-rep max load and three minutes of rest between sets, three times per week for 6 weeks.

Unfortunately, the grip-width on the bench press was not specified. One-rep max load was retested every 3 weeks, allowing the readjustment of the training load.

The researchers found the cross-sectional area at the belly of the pectoralis major had increased by 17.6% on average.

This amounts to a 0.42% increase in cross-sectional area per day, slightly more than double the 0.20% elbow flexor increase.

As a result, this study does indeed suggest the barbell bench press is an excellent exercise for growing the pectoralis major.

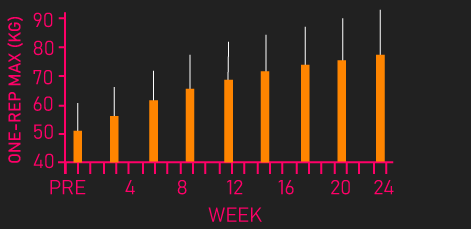

Ogasawara et al. had 7 untrained men train the barbell bench press for 3 sets of 10 reps with a 75% one-rep max load and 2-3 minutes of rest between sets, three times per week for 24 weeks.

A 2x shoulder-width grip was used on the barbell. One-rep max on the bench press was measured every 3 weeks, allowing the readjustment of training load.

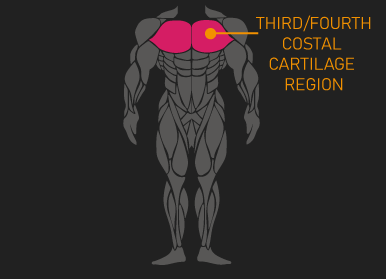

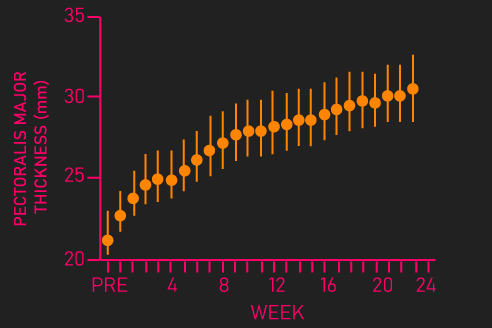

Muscle thickness of the pectoralis major was measured at the middle of the clavicular line between the third and fourth costal cartilages every week throughout the 24 weeks.

As shown in the graph below, increases in thickness steadily increased throughout the 24 weeks. Furthermore, the graph below shows the increase in bench press one-rep max during every 3rd week of the 24 weeks.

Looking at these two graphs together, we can see that as one-rep max increased on the bench press, so did pectoralis major thickness.

By the end of the 24 weeks, the subjects had experienced an average 43% increase in pectoralis major thickness, equating to a 0.26% increase in thickness per day.

This, like the Yasuda et al. study, is above the average elbow flexor increase provided by numerous studies. However, I should note muscle thickness and muscle cross-sectional area is not the same measurement, so making the comparison might not be as sensible here.

Even so, I think most would agree this study implies the bench press is an effective movement for pectoralis major growth.

So far, one study (Brandao et al.) suggests the bench press is fairly decent at growing the pectoralis major, while two (Yasuda et al. & Ogasawara et al.) indicate the bench press is excellent at growing the pectoralis major.

However, these three studies assessed measures of pectoralis major growth in only one region, more or less the fibers of the sternal head.

What about the other regions of the pectoralis major?

Bench Press and Regional Pectoralis Major Growth

Fortunately, two studies have assessed measures of muscle growth in different regions of the pectoralis major after training the barbell bench press.

Davies et al. had a group of trained men (average of 5 years training experience) train the barbell bench press for 4 sets of 5 reps with an 85% one-rep max load and 5 minutes of rest, twice per week for 8 weeks.

Unfortunately, the grip-width on the bench press was not specified. One-rep max load was retested every 2 weeks, allowing the readjustment of the training load.

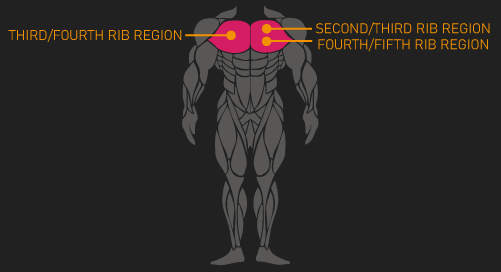

The researchers measured the thickness of the pectoralis major in three regions: between the spaces of ribs 2 and 3 (upper region), between the spaces of ribs 3 and 4 (middle regions), and between the spaces of ribs 4 and 5 (lower region).

As a note, the upper region can be considered the fibers of the clavicular head, the middle region the fibers of the sternal head, and the lower region the fibers of the costal head.

Of course, remember this is somewhat arbitrary. As we saw earlier, there is no universal way to divide the pectoralis major.

On average, the upper region experienced a 7.44% increase in thickness, corresponding to a 0.13% per day.

The middle region, on average, experienced a 10.06% increase in thickness, corresponding to a 0.18% increase in thickness per day.

Finally, the lower region, on average, experienced a 7.45% increase in thickness, corresponding to a 0.13% increase in thickness per day.

All of these values are below the 0.2% average elbow flexor cross-sectional area increase per day provided by multiple studies. However, again, this measurement was muscle thickness, so this comparison may not be sensible.

But probably more importantly, the subjects in this Davies et al. study were trained, they had an average of 5 years of training experience. The 0.2% elbow flexor cross-sectional area increase per day was from studies mainly involving untrained subjects.

With this in mind, I would say the results of this study seem pretty good.

Comparing thickness increases between regions of the pectoralis major, there were not really any extreme differences. Average increases were more or less identical between the upper and lower region, though they were both less in comparison to the middle region.

Another study by Ogasawara et al. had a group of untrained men perform the barbell bench press for 3 sets of 10 reps with a 75% one-rep max load and 2-3 minutes of rest, three times per week for 24 weeks.

A 2x shoulder-width grip was used on the barbell. One-rep max was reassessed every 3 weeks, enabling the readjustment of training loads.

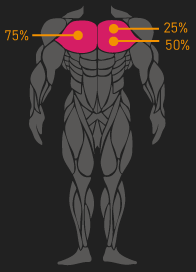

The researchers assessed the cross-sectional area of the pectoralis major at 25% (upper region), 50% (middle region), and 75% (lower region) of the pectoralis major length.

On average, the upper region experienced a 36.3% increase in cross-sectional area, equating to a 0.22% increase per day.

The middle region, on average, experienced a 37.3% increase in cross-sectional area, also equating to roughly a 0.22% increase per day.

Finally, on average, the lower region experienced a 40% increase in cross-sectional area, equating to a 0.24% increase per day.

The subjects of this study were untrained, also, the measurement used was cross-sectional area, allowing a more fair comparison with the elbow flexor increase provided by the Wernbom et al. review study.

For all three regions, increases per day were slightly greater than the average 0.2% increase for the elbow flexors, indicating the bench press does an excellent job at developing the upper, middle, and lower regions of the pectoralis major.

Moreover, increases across the three regions were more or less the same, suggesting the bench press targets these areas near equally.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Summary of the Longitudinal Evidence

From the research evaluating measures of pectoralis major growth at only one region (the sternal region for all papers), one study (Brandao et al.) suggests the bench press is fairly decent, while two (Yasuda et al. & Ogasawara et al.) indicate the bench press is excellent at growing the pectoralis major.

The two papers (Davies et al. & Ogasawara et al.) assessing regional pectoralis major growth further support the idea the bench press may be excellent at growing the sternal head of the pectoralis major.

However, regarding the clavicular (upper) and costal (lower) portions, these two papers do not entirely agree.

Davies et al. study suggests that although the clavicular and costal heads may experience similar and respectable growth, it is slightly less than sternal head growth.

Conversely, Ogasawara et al. suggest that all three regions experience near-identical rates of hypertrophy.

Differences between the studies, such as the subject’s training experience, could explain these discrepancies.

So, is the bench press enough for pectoralis major hypertrophy?

All in all, the research does appear to suggest the barbell bench press may close to ideal for developing the sternal region.

For the clavicular and costal regions, although the research suggests meaningful growth will occur in these regions from bench pressing, whether this amount of growth is comparable to the sternal region is a little less clear. Ogasawara et al. suggest it could be, whereas Davies et al. suggests it might not be.

Limitations of the Current Evidence

There are some noteworthy limitations of the current evidence that must be considered.

Firstly, all of the five longitudinal studies lasted 24 weeks or less. Additionally, four of these were conducted on untrained individuals.

In the longer term, it’s quite possible that training only the barbell bench press for your pectoralis major would lead to training plateaus.

Altering your training variables, which could include more exercise variation for a muscle group, could be an effective means of getting past stagnations. In this way, other pectoralis major exercises could be useful.

Secondly, the five studies evaluated the impacts of training only the barbell bench press on measures of pectoralis major growth. No study had another group performing the barbell bench press in combination with other pectoralis major exercises for comparison.

In other words, it remains possible that if we had two groups, one performing only the barbell bench press and another performing the barbell bench press with other pectoralis major exercises (with both groups performing the same number of weekly sets for the pectoralis major), the group performing the barbell bench press with other exercises could experience greater overall pectoralis major hypertrophy.

Without research on these two areas, I believe we cannot truly conclude if the barbell bench press is enough for pectoralis major hypertrophy.

Exercises That May Complement the Bench Press

From theoretical as well as some experimental evidence, there are some exercises that could complement the barbell bench press.

Strech Mediated Hypertrophy

Another positive thing about the barbell bench press we have not mentioned yet is it stretches the pectoralis major under load to some degree. This is noteworthy, as when the pectoralis major is stretched, research indicates its sarcomeres (the contractile units of a muscle) are stretched sufficiently to produce passive tension.

Note, this information applies to the clavicular, sternal, and costal head.

Passive tension from the sarcomeres, in combination with the high amounts of force produced by the sarcomeres (termed active tension) during the lower portion of the bench press, means a great deal of overall mechanical tension.

Mechanical tension is currently the best-categorized driver of muscle growth in the research.

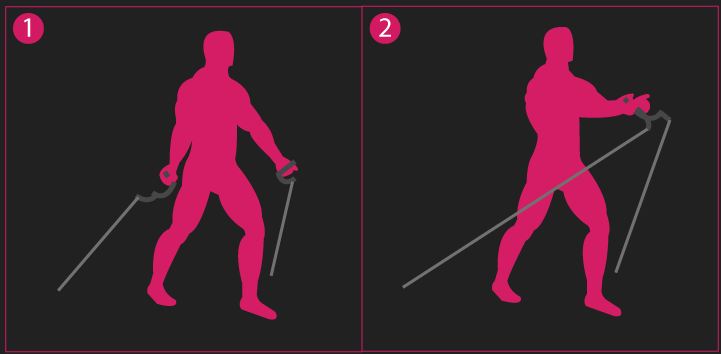

However, there are exercises that achieve a greater stretch of the pectoralis major compared to the barbell bench press. For example, the seated machine chest fly.

Dumbbell flys would also count here. However, I think a seated chest fly machine gives you more stability and control over the motion, likely making the exercise safer. Seated or standing chest flyes with a cable would also likely work well.

Exercises such as these could complement the barbell bench press by providing stretch-mediated hypertrophy the barbell bench press would otherwise not have.

Now, flies do have a reputation for being injurious. If you have any shoulder issues or develop any shoulder issues, it’s probably safer to avoid this movement.

Exercises for the Clavicular Head

As mentioned earlier, for the clavicular region, although the research suggests meaningful growth will occur in this region from bench pressing, whether this growth is comparable to the sternal region is a little less clear. Ogasawara et al. suggest it could be, whereas Davies et al. suggests it might not be.

Nevertheless, anecdotally, it’s common to hear the upper chest being a problem area for many people, despite training the flat barbell bench press.

In response to this, the incline bench press is often recommended.

The incline barbell bench press does begin with greater shoulder flexion, meaning greater degrees of shoulder flexion would occur throughout a full range of motion incline bench press compared to a flat bench press.

When discussing the internal moment arm research much earlier, we saw that the clavicular head, along with the anterior deltoid, is heavily involved in shoulder flexion.

Accordingly, the incline bench press should recruit the fibers of the clavicular head more than the flat bench press.

Interestingly though, electromyography research assessing clavicular head activation during incline and flat bench pressing is conflicting.

Lauver et al. found similar activation of the clavicular head between a 30-degree and 45-degree incline barbell bench press, both of which displayed greater activation than a 0-degree (flat) and 15-degree decline barbell bench press.

Similarly, Coratella et al. found greater clavicular head activation with a 45-degree incline barbell bench press compared to a 0-degree and 15-degree decline barbell bench press.

Rodriguez-Radio et al. compared clavicular head activation between a 0-degree (flat), 15-degree, 30-degree, 45-degree, and 60-degree incline barbell bench press. Interestingly, activation was greatest with a 30-degree incline, while both 45-degree and 60-degree inclines produced slightly less activation than a 0 degree (flat) barbell bench press.

Stephan and Amstrong found no difference in clavicular head activation between a 30-degree incline barbell bench press and a 15-degree decline bench press.

Likewise, Saeterbakken et al. found similar clavicular head activation between a 25-degree incline, 0-degree incline, and 25-degree decline barbell bench press.

So, the electromyography research is completely conflicting, and unfortunately, cannot inform us of a potentially optimal incline angle for the clavicular head.

Electromyography does have noteworthy limitations, and so we probably shouldn’t get too caught up in this data.

There actually is one longitudinal paper assessing the effects of incline and flat bench pressing on clavicular, sternal, and costal head thickness. However, a smith machine was used.

Chavez et al. split 47 untrained men into one of three groups: a horizontal bench press group, an incline bench press group, or a combination of both group.

All three groups trained once per week for 8 weeks.

The horizontal bench press group trained the flat smith machine bench press for 4 sets to failure with an 8-12 rep max load each session, the incline bench press group also did this but with a 44-degree incline smith machine bench press.

The combination of both group trained each of those two exercises for 2 sets to failure with an 8-12 rep max load each session.

The researchers found that increases in sternal and costal thickness were similar between all three groups. However, increases in clavicular head thickness were greater for the incline bench press group.

Therefore, this study suggests that at least 4 sets per session on the incline smith bench press per week (2 sets from the combination of both group was not enough) provides the greatest increases in clavicular head growth.

Now, the smith machine was used. Mechanics between a smith machine and a barbell bench press are not identical.

Nevertheless, perhaps this study indicates a 44-degree incline barbell bench press may provide greater clavicular head growth than a flat barbell bench press.

Ultimately, if, at some point during your training career, you feel your upper chest is under-developed, you may wish to experiment with the incline barbell bench press at various angles.

Aside from the incline barbell bench press, there are other exercises that could potentially be ideal for clavicular head development.

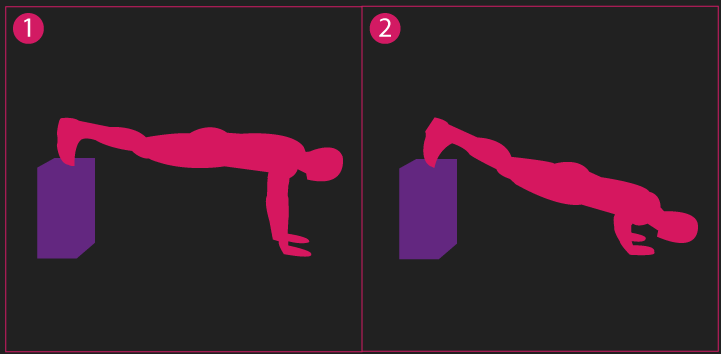

Such as incline dumbbell bench presses, decline push-ups, and a low cable chest fly.

Exercises for the Costal Head

Similar to the clavicular head, although the research suggests meaningful growth will occur in the costal head from bench pressing, whether this amount of growth is comparable to the sternal head is a little less clear. Ogasawara et al. suggest it could be, whereas Davies et al. suggests it might not be.

Often, a decline barbell bench press is recommended for the lower chest.

However, when compared to the flat barbell bench press, electromyography research suggests the decline bench press does not elicit greater costal or sternocostal head activation.

Lauver et al. and Coratella et al. found similar costal head activation between a flat barbell bench press and a 15-degree incline barbell bench press.

Saeterbakken et al. also found similar sternocostal head activation between a 25-degree decline bench press and a flat barbell bench press.

Again, electromyography has limitations, so we should approach these results with caution. On top of this, unfortunately, we do not have any longitudinal research here.

An exercise that theoretically may be good for developing the costal head is a dumbbell or barbell pullover.

Recall that when looking at the research on internal moment arms, the costal head, at high angles of shoulder flexion, is involved in shoulder extension.

During the eccentric (lowering) phase of a pullover, the shoulders are flexed to high angles. During the concentric (lifting) phase, shoulder extension occurs. This motion should do a good job at recruiting the costal head of the pectoralis major.

In the research, the dumbbell pullover has been shown to highly activate the pectoralis major (one, two, and three). However, all three of these studies did assess activation at the sternal or clavicular head, so we cannot necessarily be certain of the costal head.

Regardless, in most cases, individuals should be able to feel a large portion of the pectoralis major being trained during a pullover.

Conclusion

Through analyzing the functions of the pectoralis major, the motions that occur during the barbell bench press, and the longitudinal research, the bench press does appear to be an excellent exercise for pectoralis major hypertrophy.

Meaningful growth of clavicular, sternal, and costal heads of the pectoralis major will likely occur through barbell bench pressing.

However, the limitations of the current research limit our ability to truly answer the article’s primary question. Specifically, no paper has assessed the impacts on pectoralis major hypertrophy after training the barbell bench press for longer than 24 weeks, additionally, no paper has compared barbell bench press training only to bench pressing in combination with other pectoralis major exercises.

Ultimately, at the very least, pectoralis major growth would likely not be harmed with the inclusion of exercises such as the ones listed in the final section of the article. If anything, they could very much enhance overall pectoralis major development.

Furthermore, exercise variation in the long term would probably make training more enjoyable for the majority of people.

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.

Dear House:

Your site is very, very helpful in settling many of the questions in a reasonable way. I also appreciate he use of charts/diagrams which help to explain principles!

In the Bench Press; I know there is a good amount of front delt that is trained. And by manipulating the grip width I can emphasize the pecs or the triceps slightly differently.

I would use the bench press much more for front delts, but the move sometimes irritates my shoulder joints….

What about machine flyes or pec dek: Does this move use the front delts as well…I just can’t feel them very much during several sets. Is there a way to do some kind of flying movement and emphasize the front delts more?

I look forward to checking out ALL of your articles eventually. Thank you for any input.