It’s not uncommon to hear that volume drives muscle hypertrophy.

Specifically, it’s thought more volume could produce more muscle hypertrophy, probably up until a certain point.

However, volume is quite a broad term. In general, it refers to how much work you perform.

This can be quantified in a variety of ways, including:

- The number of sets you perform for an exercise or muscle group

- The product of the number of sets and repetitions you perform (sets x reps)

- The product of the number of sets, repetitions, and loads you use (sets x reps x load)

- Even the product of the number of sets, repetitions, load, and range of motion you use (sets x reps x load x range of motion)

Volume load is the product of the number of sets, repetitions, and loads you use. For example, if you perform 3 sets of 10 repetitions on the barbell bench press with a 100kg load, this equals a volume load of 3000kg for this exercise.

It’s not uncommon to see individuals state that volume load is what drives muscle hypertrophy. I’ve even come across numerous researchers who have suggested this in their papers.

In this article, I’ll detail why this is a mistake, and why I believe volume load is actually unrelated to muscle hypertrophy.

First, we’ll evaluate some research that may lead you to believe volume load drives hypertrophy, then we’ll then look at numerous other papers which demonstrate volume load is not related to hypertrophy.

Finally, we’ll briefly touch on what form of volume likely drives hypertrophy.

Evidence Supporting the Idea Volume Load Is Related to Muscle Hypertrophy

Let us begin with the research that may lead you to assume volume load drives muscle hypertrophy.

One example comes from the research on rep ranges.

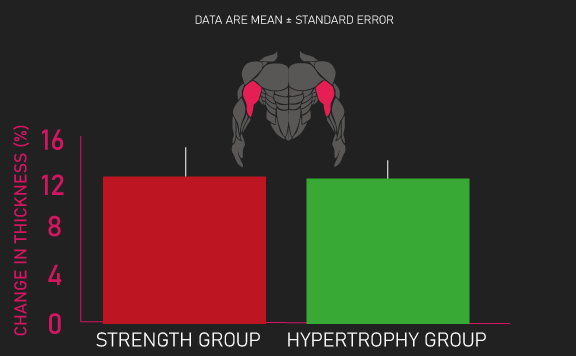

Schoenfeld et al. had 17 men with at least 1 year of training experience perform a range of exercises.

The exercises were the incline bench press, flat bench press, chest press, wide grip lat pulldown, close grip lat pulldown, cable seated row, back squat, leg press, and leg extension.

One group of subjects, who we’ll call a strength group, performed each exercise for 7 sets of 3 repetitions to failure (the point at which no more repetitions can be performed).

Another group of subjects, who we’ll call the hypertrophy group, performed each exercise for 3 sets of 10 repetitions to failure.

The reason the strength group performed more sets per exercise was to equate the volume load between both groups.

Both groups attempted to increase the load they used within their rep range every week.

After 8 weeks of training, the total volume load performed on each exercise was similar between both groups.

Moreover, increases in a biceps growth measurement were similar between both groups.

Therefore, given volume load was similar between both groups, and both groups seem to have experienced similar hypertrophy, you may think volume load may be driving hypertrophy.

Another example comes from the research on rest intervals.

Schoenfeld et al. had 13 men with at least 6 months of training experience perform a range of exercises each for 3 sets of repetitions to failure with an 8-12 rep-max load, three times per week for 8 weeks. All subjects aimed to increase the load used within the rep range every week.

The exercises performed included the back squat, leg press, leg extension, bench press, overhead press, lat pull-down, and cable row.

One group of subjects, who we’ll call a long rest group, performed this while resting for 3 minutes between sets.

Another group of subjects, who we’ll call a short rest group, performed this while resting for 1 minute between sets.

Throughout the 8 weeks of training, the long rest group was achieving greater volume loads on all their exercises versus the short rest group. This makes sense, as resting for longer between sets enables you to perform more repetitions to failure, thus increasing the volume load.

By the end of the study, increases in growth measurements for the elbow flexors, triceps brachii, anterior quadriceps, and vastus lateralis favored the long rest group.

Therefore, as the long rest group performed higher volume loads, and experienced greater muscle growth, the results would lead you to assume higher volume loads drive more muscle hypertrophy.

So, the two examples we’ve just given supports the idea that volume load may drive hypertrophy.

If studies like these were the only ones that existed, the evidence would be indeed promising that volume load is a driver of hypertrophy.

However, there do exist many other studies in which volume load appears to be unrelated to hypertrophy.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Evidence Against the Idea Volume Load Is Related to Muscle Hypertrophy

If we examined the research on rep ranges in more depth, we’d find great evidence volume load does not drive muscle hypertrophy.

As explored in previous articles, there’s quite a bit of evidence that with all other training variables equal, performing repetitions to or very close to failure with a 30% one-rep max load is as effective for muscle hypertrophy as performing repetitions to or very close to failure with an 80% one-rep max load.

As a note, an individual can roughly perform 30-ish repetitions to failure with a 30% one-rep max load, and roughly 8 to 12 repetitions to failure with an 80% one-rep max load.

Now, here’s the thing, the volume load you achieve with a 30% one-rep max load is greater than the volume load you achieve with an 80% one-rep max load.

For instance, Lim et al. had 21 previously untrained men train the leg press and leg extension each for three sets, three times per week for 10 weeks.

One group of subjects performed repetitions to failure each set with a 30% one-rep max load, while another group of subjects performed repetitions to failure each set with an 80% one-rep max load.

The average volume load used for both exercises was greater for the subjects that trained with a 30% one-rep max load.

However, growth of slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibers from the vastus lateralis muscle was similar between training with a 30% and 80% one-rep max load.

Therefore, the rep range research demonstrates that higher volume loads do not necessarily produce more muscle hypertrophy.

Additionally, the rep range research also demonstrates that your ability to increase the volume load you perform over time probably doesn’t relate to muscle hypertrophy either.

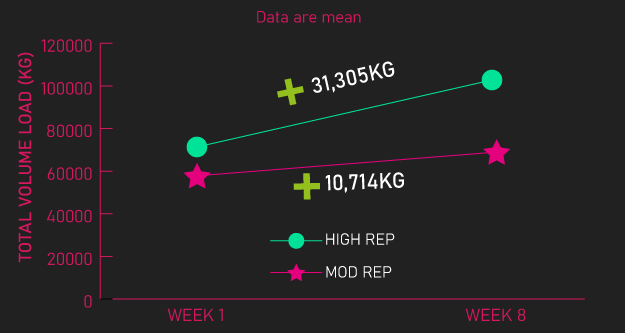

Illustrating this, Schoenfeld et al. had a group of men with between 1.5 to 9 years of training experience perform a range of exercises each for 3 sets, three times per week for 8 weeks.

The exercises performed included the back squat, leg press, leg extension, bench press, overhead press, lat pull-down, and cable row.

One group of subjects, who we’ll call a high rep group, performed 25-35 repetitions to failure each set.

Another group of subjects, who we’ll call a moderate rep group, performed 8-12 repetitions to failure each set.

Both groups attempted to increase the load they could lift within their rep ranges every week.

By the 8th and final week of the study, the high rep group had increased their volume load performed for all exercises by 31,305kg compared to the first week.

Opposingly, the moderate rep group, compared to the first week, increased their volume load performed for all exercises only by 10,714kg.

However, as we know from other data, both the high rep and moderate rep groups would likely have experienced similar muscle hypertrophy, indicating your ability to increase volume load over time is likely not related to muscle hypertrophy.

Progressing further, the research on training to failure further supports the idea volume load is not a driver of muscle hypertrophy.

Training to failure would result in a higher volume load compared to stopping your repetitions a couple short of failure.

However, the research generally seems to show that performing your repetitions 1 to 3 reps away from failure is similarly effective to training to failure for muscle hypertrophy.

For example, Santanielo et al. had men with an average of 5 years of training experience perform the unilateral leg press and the unilateral leg extension with a 75% one-rep max load, twice per week for 10 weeks.

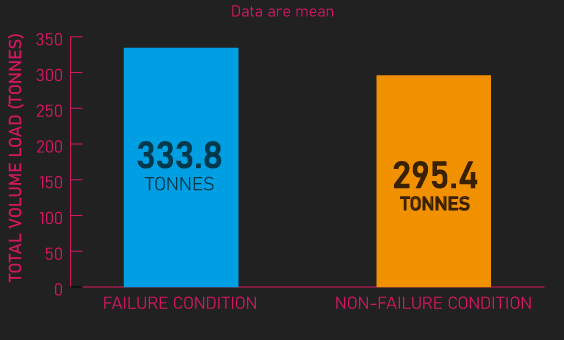

Subjects trained one leg with repetitions to failure, we’ll call this the failure condition.

Their other leg performed repetitions roughly 3-1 reps away from failure. We’ll call this the non-failure condition.

The total volume load performed in the 10 weeks was greater with the failure condition.

As a final point, there’s evidence if you equate training volume load between a condition that trains to failure, and one that trains very far from failure, muscle hypertrophy outcomes are dissimilar.

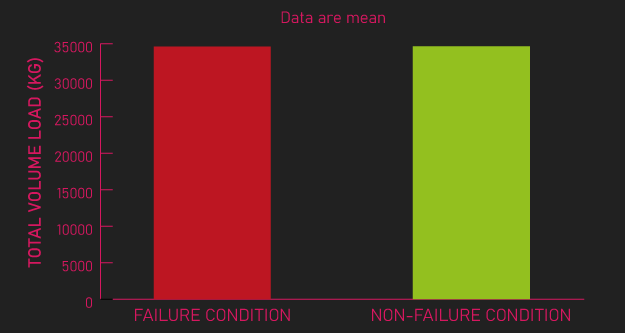

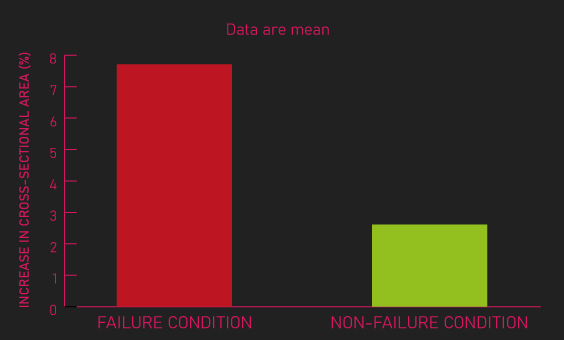

Demonstrating this, a study by Lasevicuis et al. had previously untrained men perform the unilateral leg extension with a 30% one-rep max load, twice per week for 8 weeks.

Each session, subjects trained one leg with 3 sets of repetitions to failure. We’ll call this the failure condition.

With their other leg, they performed roughly 7 sets of repetitions that were roughly 14 repetitions away from failure. We’ll call this the non-failure condition.

By the end of the study, total training volume load was similar between both conditions.

However, quadriceps growth was much greater for the failure condition, demonstrating volume load is not necessarily related to muscle hypertrophy.

Conclusion

To conclude, despite there being some evidence that may lead you to believe volume load drives hypertrophy, other studies falsify this by demonstrating volume load is unrelated to muscle hypertrophy.

So, if volume load is not the form of volume that relates to muscle growth, what is?.

It seems the number of sets you perform for your muscle groups is what appears to be related to muscle hypertrophy.

More precisely, in this case, a set would probably be defined as a bout of repetitions between 5 and 35, performed 3 or fewer repetitions from the point of failure.

We’ve explored this in further depth in another article (soon to be published).

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.