It’s almost a guarantee that if you got two people to perform the same training program, they would get different results. Why is this?

Genetics, nutrition, and sleep may be some factors that instantly come to your mind, and all of these are unquestionably valid. But another, probably underappreciated factor, is the psychological stress levels experienced by a person.

Psychological stress is the emotional stress within your mind. There are probably an infinite number of ways you could describe psychological stress, from persistent feelings of fear, anxiety, anger, resentment, frustrations, grief, sadness, and so on and so forth.

Most of the people reading this article are probably well aware of one form or another of psychological stress.

But, how does psychological stress relate to building muscle and strength?

Oftentimes, we may simplify training. For example, two-factor fitness model, training stimulates fitness + fatigue, once fatigue diminishes your performance increases.

However, remember we’re talking about the human body, an extraordinarily complex machine.

Your brain contains around 86 billion neurons, and at any given second in time, one estimate suggests there are 37 with 21 zeros reactions taking place in your body.

Thus, it’s clear to see simplifying training and its response is not easy. The fact is your mind interacts with your physiology. We saw in a previous article that the mere belief you’re taking anabolic steroids (when you are actually not) skyrockets your strength gains.

In this article, we’ll be exploring how psychological stress impacts recovery after a training session, your long-term strength and muscle gains, and then we’ll wrap up with a brief mention of methods to potentially reduce psychological stress.

Part I: Psychological Stress Screws up Your Recovery

Let us first examine how psychological stress impacts your recovery after a training session.

This study has 210 students in resistance training classes complete a test to determine their perceived levels of stress. That is, how much stress do they feel they have.

Ultimately, 31 individuals were recruited. 18 of them had results indicating they were low stressed individuals, while 13 of them had results indicating they were highly stressed individuals.

Now, these subjects again completed the test to determine their perceived levels of stress, to ensure the results had not changed.

Additionally, they did a test to determine the number of stressful life events taking place in the person’s life. Thus, each subject not only had their perceived stress score, but also a life event stress score.

The subjects performed a highly intense training session.

It consisted of a ramping phase and burnout phase. All of the training was done on the leg press.

The ramping phase had the performed sets of 10 reps with progressively heavier weights until they worked up to a weight with which 10 reps could not be completed. 2 minutes of rest was given between these sets.

3 minutes after this, they moved on the burnout phase. This consisted of performing 6 sets of repetitions to volitional failure. On the first set, they used a load that can be performed for a maximum of 10 repetitions (this load was of course established from the ramping phase). The second set had them reduce this load by 10%, and if subjects could perform more than 10 reps on this set, they kept training with this load throughout sets 3 to 6. If not, they used a 20% light load on the remaining sets. 3 minutes of rest between sets was used here.

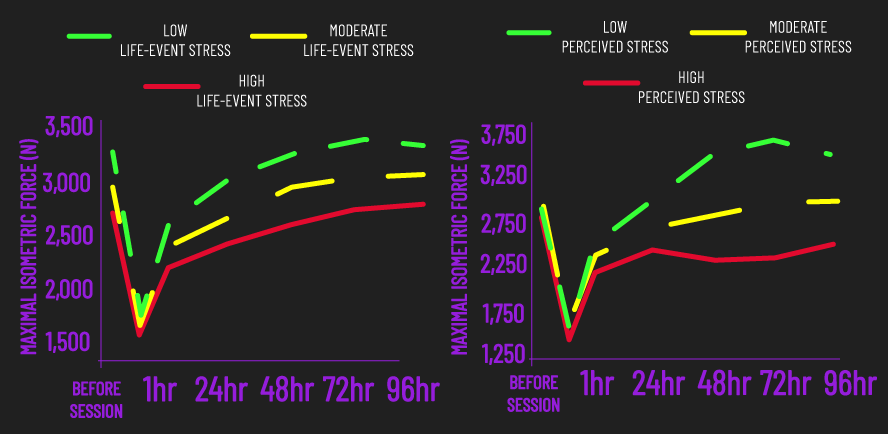

Before this training session, the researchers measured maximal isometric muscle force, muscle soreness, subjective fatigue, and subjective energy, were also measured.

All of these measures were re-tested 1 hour, 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours after the training session.

What were the findings?

Higher stressed individuals (as measured by both the perceived and life event stress measures) took longer to recover their maximal isometric muscle force on the leg press. Looking at the data, low stressed individuals recovered within 48 hours, while the highly stressed individuals just about recovered within 96 hours, which is double the time.

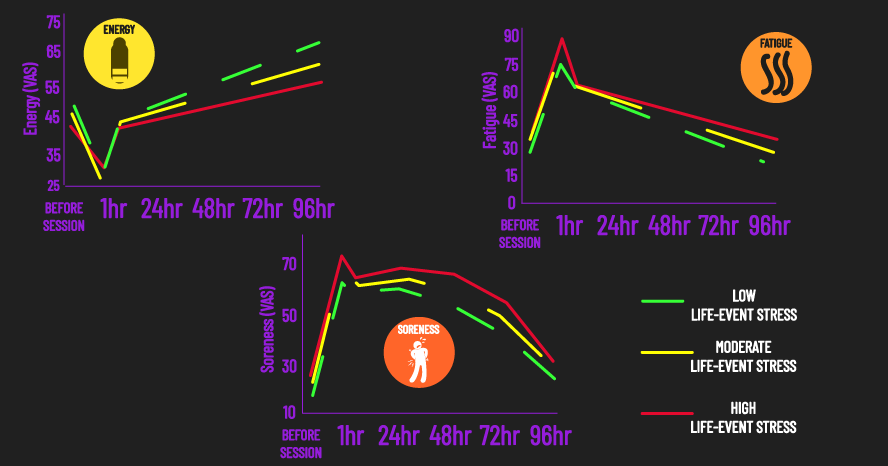

Physical energy, fatigue, and soreness also took longer to return to baseline in the highly stressed individuals (as measured by life event stress).

Perceived levels of stress did not have an effect on soreness or fatigue scores, but it did have an effect on energy, such that highly stressed individuals with this score took longer for their energy levels to return.

It’s worth mentioning that before the intense training session, all the measurements were similar between the highly, moderately, and low stressed individuals. Moreover, all these subjects performed similar workloads and saw similar max and average heart rate responses, so differences in before measurements or differences in training effort cannot explain the results we’ve overviewed.

Thus, the data demonstrate strongly that stress (both perceived and life event stresses) interferes and prolongs your recovery durations.

Part II: Psychological Stress Screws up Your Long-Term Gains

How does psychological stress impact long-term muscle and strength gains?

For this, we have this study.

81 men and 54 women were recruited. The subjects were classified as either low stressed or high stress individuals based on a test that incorporated both life event stress and their perceived stress impacts.

All subjects trained a range of exercises twice per week for 12 weeks.

There were three mesocycles throughout the 12 weeks. The first 4 weeks was a hypertrophy cycle, with 3 sets of 10 repetitions performed per exercise. The second 4 weeks was a strength cycle, with 3 sets of 5 repetitions performed per exercise, while the last 4 weeks was a power cycle, with each exercise trained with 3 sets of 3 repetitions.

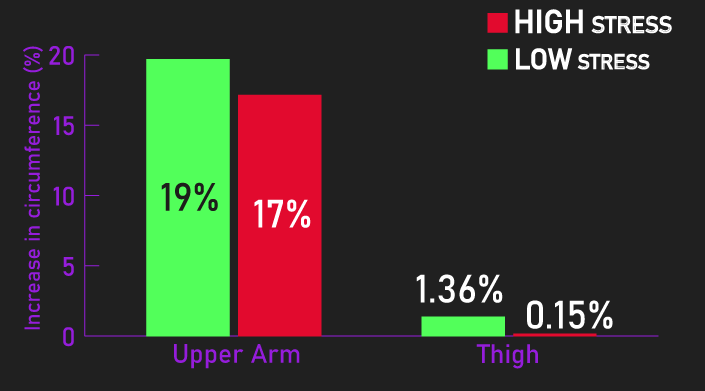

It was found bench press and squat strength gains (as measured by one-rep max) were greater for the low stressed versus high stressed individuals.

Increases in upper arm and thigh circumference were not statistically different between the low and high stressed individuals. However, the percentages do appear to favour the low stressed individuals. Speaking very non scientifically, I think this could be a real difference that the study was just underpowered to find, but at the same time, it could just be due to chance.

It’s also worth pointing out that circumference is a very indirect measure of muscle growth, if more direct measures of muscle growth (such as ultrasound or MRI measures), perhaps we would see a difference between the low and high stressed individuals, but this is me speculating.

Nevertheless, at the least, this study indicates psychological stress interferes with strength gains.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Part III: Some Research on Reducing Psychological Stress

Based on the data overviewed, it appears psychological stress can extend recovery durations and impair long-term adaptations.

It’s worth also noting that other data indicates high stressed individuals are more susceptible to illnesses and injuries.

Thus, you’re going to want to do your utmost to minimize stress, we’ll discuss some potential things that can help shortly.

But I also want to discuss another potential takeaway from this article.

That is, there are cases where psychological stress is unpredictable and uncontrollable. In events like these, given stress will negatively influence your recovery and adaptability. it might be best to go easy with your training or give yourself a break. Remember, muscle memory is real. Humans (and other animals too) have an accelerated ability to regain lost strength and muscle, so training breaks or periods of light training should not worry you. Moreover, there’s some potential reason to believe training breaks at least may be beneficial for resensitizing your anabolic pathways, but I’ll save this for another article.

Anyway, let us detail some potential ways to minimize psychological stress.

The first potential way is via practicing meditation. Now, there are numerous different forms of meditation, but I think pretty much all of them can probably reduce psychological stress.

The literature suggests meditation can reduce activity of the amygdala (sometimes called the brain’s fear center), and even potentially reduce the size of the amygdala in the long-term while concurrently increasing grey matter in brain regions involved in learning, memory processing, and emotion regulation.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis on nearly 1,300 adults found meditation may decrease anxiety, with the strongest effect seen for those with the most anxiety.

The second potential way to reduce psychological stress is through breath work. There are numerous types of breathing exercises that can help. It’s worth noting that when you breathe in, your heart rate increases, while when you breathe out, your heart rate decreases. So breathing in a way that results in you exhaling more than you inhale can be a great way to induce relaxation and calmness.

One real time is the double inhale followed by a long exhale. I first heard about this from Andrew Huberman. It seems to be a great way to instantly help relive some stress.

Moving on, from the literature, there’s evidence diaphragmatic breathing sessions (also called belling breathing) where you focus on deep inhales followed by long slow exhales can increase attention abilities, enhance wellbeing, and reduce cortisol levels (cortisol is also known as the stress hormone)

The third potential way is to spending time in nature. There’s evidence visiting natural environments can be beneficial in reducing both physical and psychological stress levels.

Of course, depending on where you live, spending time in nature isn’t always viable, another fourth potential way is just to walk more. Its evident humans were designed to move and be active, and we thrive when we do so. Higher daily step counts (even potentially more than 10,000 daily steps) have been associated with lower risks of dying from all causes. Moreover, higher daily steps have been associated with lower anxiety, depression, anger, fatigue, confusion, and total mood distress scores.

Of course, these are only a few of the numerous ways one could go about relieving stress, and different individuals have their own preferences and methods to deal with stress, but I hope at least some of the info detailed here can be of use to you.

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.