First and foremost, an understanding of the length-tension relationship is needed. Feel free to gloss over this part if you’re already well aware of it.

Understanding The Length-Tension Relationship

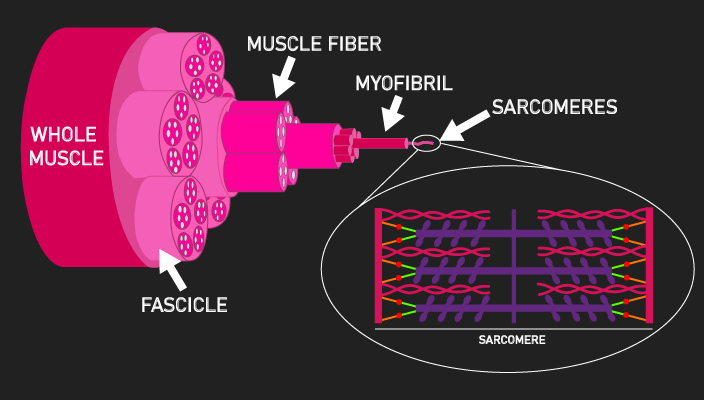

Within muscles are sarcomeres, and sarcomeres are the force generating units of muscles.

Sarcomeres have the ability to generate active tension and passive tension. Note, tension is analogous to force in this case.

Active Tension

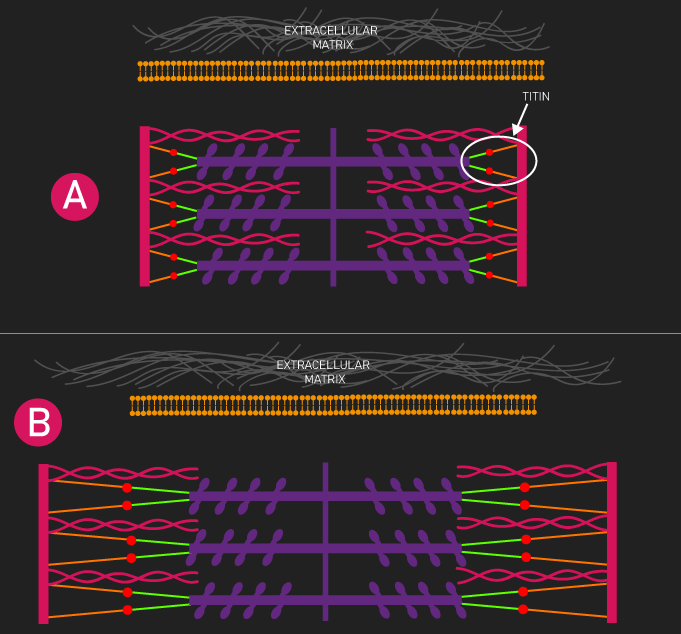

Active tension occurs when the myosin head extends from the myosin filament and pulls the actin filament towards the M-line, shortening the length of the sarcomere.

B) The myosin heads extend from the myosin filaments and attach to the actin filaments.

C) The myosin filaments pull the actin filaments towards to M-line, shortening the sarcomere length.

This action produces force that is partly transmitted longitudinally, but mainly laterally to the extracellular matrix (surrounding muscle fibers). These forces end up pulling on the tendon, resulting in muscle contraction.

Passive Tension

Passive tension is the force produced during stretch. Think of a rubber band, when you stretch a rubber band, it produces passive tension to try and resist that stretch. When you let go of the rubber band, that passive tension will snap it back into its original shape.

Titin is a protein within the sarcomere that produces passive tension when the sarcomere is stretched.

The Length-Tension Relationship

Now that we understand active and passive tension from the sarcomere, we can introduce the length-tension relationship.

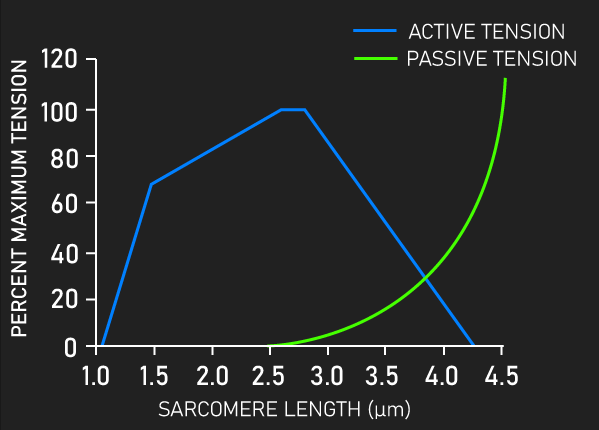

In this relationship, the length of a sarcomere is on the x axis, while the amount of tension (force) produced by a sarcomere is on the y-axis.

We can see there are two components to it. Active tension is blue, and passive tension in green.

With passive tension, we can see it sharply increases at longer sarcomere lengths. This makes sense, since passive tenson is force from the stretch of titin, we’re going to want the sarcomere to be stretched for titin to be stretched.

Note, in all of the length tension relationship graphs shown in this article, passive tension begins to develop at a sarcomere length of 2.5μm. This would likely not be the case with all muscles. evidence indicates the passive tension curve is variable (much more so than the active tension curve), so keep this in mind.

With the active tension component of the length-tension relationship, there are generally 5 distinct components to it.

1) The start of the ascending limb of the length-tension relationhip. Excessively short sarcomere lengths result in little to no force production. At this length, the opposite actin filaments overlap with one another to some degree. This overlap prevents many of the myosin heads from extending and pulling on the correct actin filament. As a result, little force is produced.

2) Increasing the length of the sarcomere slightly removes some of the overlap between the opposite actin filaments, allowing some of the myosin heads to extend and pull on the actin filament. Therefore, the sarcomere can generate some force.

3) Increasing the sarcomere length further removes any opposing actin filament overlap. Consequently, all the myosin heads can extend and pull the actin filament towards the M-line. This particular region of the length-tension relationship is known as the optimal length, as it is the length that allows the highest active tension. As a note, the optimal length isn’t one particular length, it is a region (2.6-2.8μm in humans), the small plateau region on the graph demonstrates this.

4) Further increasing the length of the sarcomere results in the actin filaments moving away from the myosin filament. We are now on what’s called the descending limb of the length-tension relationship. This is where some myosin heads are not overlapping with the actin filament, meaning they cannot extend and pull the actin filament. Because fewer myosin heads can contribute to force here, active force production is less.

5) At this point, there is no overlap between the myosin heads and actin filaments, thus no myosin head can extend and pull the actin filament. Accordingly, no more active tension can be produced.

Passive Tension & Muscle Hypertrophy

It turns out within and around your muscle fibers are mechanosensors that are able to “detect” both active and passive tension, and convert this tension into a hypertrophy signal.

In the literature, training muscles at longer muscle lengths (reaching a more stretched position) tends to build more muscle. Although the context here is important. For more details, see this video. Many have speculated the reason that training muscles at longer lengths builds more muscle is because it involves the addition of passive tension, which means an “extra” signal for growth.

However, some have argued that this cannot apply to all muscles. The reason they give for this is that a muscle must have sarcomeres that can actually reach the descending limb of the length-tension relationship to experience passive tension and thereby experience the “extra” signal for growth. But they say that not all muscles have sarcomeres that actually reach the descending limb. This may sound confusing, but let’s explain what they’re talking about.

Example: The Working Sarcomere Lengths of the Biceps (From One Study)

It is logical to assume that when the whole muscle is fully shortened (like at the top of a biceps curl), all the sarcomeres within the biceps are fully shortened. Likewise, when the muscle is stretched (like at the bottom of a biceps curl), all the sarcomeres within the biceps are stretched.

Although this is a very reasonable assumption, it isn’t actually always the case.

Different muscles have their sarcomeres organized in different ways that directly impact the length their sarcomeres can work through during any movement.

With the biceps, this cadaver study by Murrary et al. indicates when the elbow is flexed to 120 degrees (near the biceps being fully shortened), the sarcomeres of the biceps short and long heads are at the very start of the length tension-relationship. However, when the elbow is straightened out to 20 degrees of elbow flexion (when the biceps are stretched to a degree), the sarcomeres of the biceps short and long heads are at the middle area of the length-tension relationship (near the plateau region of the active tension component).

In other words, despite the biceps being stretched to a degree when the elbows are flexed to 20 degrees, its sarcomeres are not stretched fully.

Therefore, some people have used this data to suggest since the sarcomeres are not stretched extensively, the biceps should not grow more when exposed to stretch during an exercise.

I’ve also seen people reference data on other muscles that indicates their sarcomeres do not get stretched extensively, and they use this to conclude that training them at longer muscle lengths will not be superior.

However, I think there are a range of limitations and considerations with this idea.

Limitations & Considerations With This Data

-

- There is some evidence suggesting that during eccentric contractions (which happens in most typical exercises), titin might actually be capable of producing passive tension earlier and to a greater magnitude. As far as I’m aware, this is not captured in much of the data exploring sarcomere lengths. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the precise sarcomere length at which passive tension is generated is variable between muscles. What this implies is just because a certain paper suggests that the sarcomeres of a muscle may not reach the descending limb, that does not mean that minimal passive tension is occuring.

- The research evaluating sarcomere lengths typically examine a small proportion of sarcomeres relative to the overall muscle. This is problematic as it’s likely not all the sarcomeres within a single muscle go through identical lengths during a movement . In other words, when a muscle is stretched, it’s possible for some of its sarcomeres to be stretched quite a bit and other sarcomeres to not be stretched as much. It’s also worth pointing out that titin isn’t the only source of passive tension. Although it’s possible titin is the predominant source of passive tension in the human body, the extracellular matrix surrounding muscle fibers is also capable of generating passive tension, and perhaps this might be capable of signaling hypertrophy too.

- As we overviewed, there is some data suggesting that the sarcomeres of the biceps do not reach the descending limb. Yet, we have evidence that the biceps may grow more with a range of motion that reaches longer lengths (one and two). Thus, it is apparent that predications generated from sarcomere data does not neccessarily align with data actually measuring growth.

- There are also differences between people for the same muscle. That is, some people may have many sarcomeres that reach the descending limb for a given muscle, while others do not.

Conclusion

While knowing about the length-tension relationship is useful, due to the limitations and considerations outlined, I am hesistant to use data exploring the length of a muscle’s sarcomeres to infer whether that muscle will benefit from being trained at longer muscle lengths or not. Currently, there’s still a lot we do not know about muscle growth.

Instead, I think the research actually examining muscle growth after comparing two different training interventions is what’s most important.