The flat barbell bench press is probably the most popular upper body exercise.

This is probably quite justified, it’s a time-tested and highly effective muscle and strength builder.

As examined previously at House of Hypertrophy, the current literature demonstrates the flat barbell bench press is highly effective for chest hypertrophy. Moreover, the current data indicates the barbell bench press may near equivalently and significantly develop the upper, middle, and lower chest regions.

The push-up is also a well-known upper-body exercise.

However, when directly compared to the bench press for muscle hypertrophy, it’s far from uncommon for individuals to assume the bench press is considerably superior.

In this article, we’re going to examine the validity of this assumption, is the bench press truly superior to the push-up for muscle hypertrophy?

To do this, we’ll thoroughly examine the existing literature comparing the push-up and bench press, including both longitudinal and acute studies.

Table of Contents

Longitudinal Research: Bench Press vs Push-up

To kick things off, there are currently two longitudinal studies comparing the bench press and push-up for increasing measures of muscle hypertrophy.

Study One: Kikuchi & Nakazato Study

The first was conducted by two Japanese researchers, named Kikuchi and Nakazto, in 2017.

Protocol

18 young men with at least a year of resistance training experience were allocated into a bench press or push-up group.

Both groups trained twice per week for 8 weeks.

Each session, the bench press group trained the flat barbell bench press for 3 sets of repetitions to failure (the point at which no more repetitions can be performed) with a 40% one-rep max load, using 2 minutes of rest between sets.

The push-up group, each session, utilized a push-up variation that was roughly equivalent in resistance to a 40% one-rep max bench press load. For some subjects, this meant a regular push-up, whereas for others this was some kneeling push-up variation.

Regardless of the push-up variation used, the movement was carried out for 3 sets of repetitions to failure, using 2 minutes of rest between sets.

Before going any further, some viewers may be scratching their heads at the 40% one-rep max resistance used for both exercises. Perhaps you’re thinking this study is completely flawed because a 40% one-rep max load is surely suboptimal for provoking muscle hypertrophy.

However, you’d be wrong. There’s now extensive literature demonstrating that a wide range of loads are similarly effective for hypertrophy.

A network meta-analysis by Lopez et al. combined the findings of 24 studies and observed similar muscle hypertrophy between light, moderate, and heavy loads.

Differences in sex, training status, or the muscle examined did not alter these findings.

Upon deeper inspection of the included studies, much of them had subjects train with loads ranging from 30% to 80% one-rep max. Moreover, subjects executed their repetitions at least 3 or fewer repetitions from the point of failure.

Consequently, we have high-quality evidence to suggest so long as repetitions are performed 3 or fewer from the point of failure, training with loads between 30% and 80% one-rep max produces similar hypertrophy.

Therefore, the 40% one-rep max resistance used in the Kikuchi and Nazakata study, which remember, had subjects perform repetitions to failure, is perfectly acceptable for hypertrophy.

Measurements

Returning to the study’s details, before and after the 8-week training duration, pectoralis major thickness was evaluated at the region between the third and fourth ribs, while triceps and biceps thickness was each evaluated at approximately 60% of the upper arm bone length.

Results

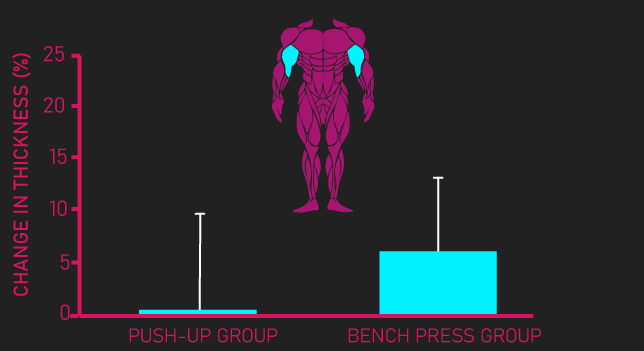

The researchers found increases in pectoralis major and triceps thickness were similar between the bench press and push-up groups.

However, biceps thickness only significantly increased in the bench press group.

This finding is quite intriguing. Most people would presume that neither the bench press nor push-ups should grow the biceps, as they act as an antagonistic muscle, not agonist, during these exercises.

What could explain this finding?

I’m not entirely certain, but the barbell bench press necessitates a fair degree of stabilization to smoothly move the barbell, perhaps the biceps actively contract to some degree to contribute towards this stabilization, thereby explaining its measurable enhancements in thickness.

Nevertheless, for the agonist muscles (at least the pectoralis major and triceps), the findings of this study indicate with all other training variables equal, the push-up can produce similar growth to the flat barbell bench press.

Study Two: Kotarsky et al.

Let’s swiftly move on to the second 2018 study by Kotarsky et al. conducted in North Dakota.

Protocol

23 men between the ages of 18 and 45, with 2-6 months of resistance training experience, were assigned into a bench press or push-up group.

Both groups trained three times per week for 4 weeks.

The bench press group performed the flat barbell bench press with a load they could complete for 3 sets of 6 repetitions. Over the following sessions, once they could successfully complete 3 sets of 8 repetitions with this load for 2 consecutive sessions, they increased the load by 4.5kg and reverted to performing 3 sets of 6 repetitions.

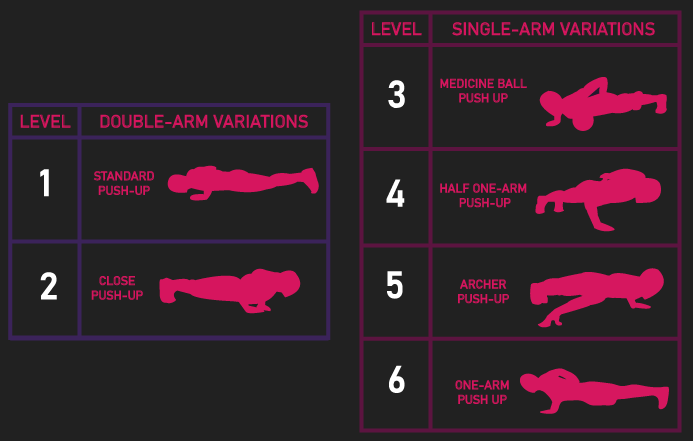

The push-up group had access to numerous push-up variations, ordered according to difficulty level, and divided into double-arm or single-arm variations.

If a subject could perform any of the single-arm variations for 3 sets of 3 repetitions, they commenced training with this variation. If not, they commenced training with a double-arm variation they could execute for 3 sets of 6 repetitions.

For those using a single-arm variant, over the following sessions, once they successfully progressed to performing it for 3 sets of 4 repetitions for 2 sessions in a row, they progressed to performing the next level while reverting to using 3 sets of 3 repetitions.

For those using a double-arm variant, over the following sessions, once they successfully progressed to performing it for 3 sets of 8 repetitions for 2 sessions in a row, they progressed to performing the next level. If this next level was still a double-arm variation, they used 3 sets of 6 repetitions, whereas if it was a single-arm variation, they used 3 sets of 3 repetitions.

Measurements

Before and after the 4-week training duration, thickness of the pectoralis major at 60% of the distance between the collar bone and nipple was evaluated.

Results

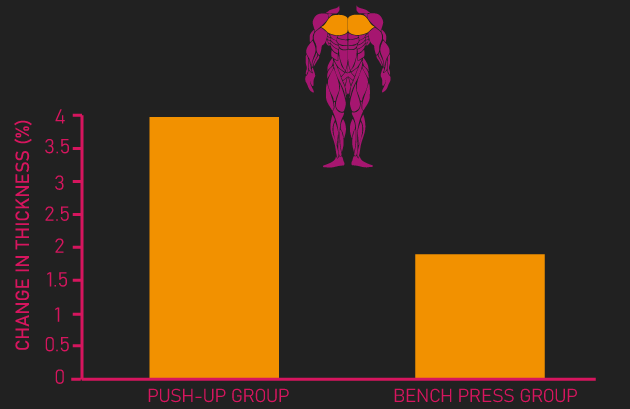

Curiously, neither group experienced statistically significant increases in pectoralis major thickness. Despite this, the numerical mean increased in both groups.

This could be due to a couple of reasons. Firstly, the study was only 4 weeks, which is a very short duration. A longer duration would probably result in statistically significant findings.

Secondly, as is unfortunately the case with most resistance training studies, the sample size was small. Small sample sizes can impact the ability to detect changes between and within groups.

Nevertheless, despite it not being classified as statistically significant, the numerical mean for pectoralis major thickness did increase in both groups.

Intriguingly, the percentages favor the push-up group. We can’t read into this too much, simply because as noted, it wasn’t statistically significant, and the sample sizes were small. Perhaps these percentages differences are simply explained by the push-up group containing subjects, on average, with a higher responsivity to training, rather than the push-up being superior to the bench press for muscle growth.

What we can probably conclude from this study, on the other hand, is that the bench press evidently did not display considerable superiority versus the push-up for muscle hypertrophy.

Acute Research: Bench Press vs Push-up

To summarize thus far, one paper by Kikuchi and Nakazato established that with all other training variables equivalent, push-ups produced alike growth of the pectoralis major and triceps to bench pressing.

Another study by Kotarsky et al., despite being quite a limited study with notable considerations, at the very least suggests the bench press was evidently not considerably superior to the push-up for pectoralis major growth.

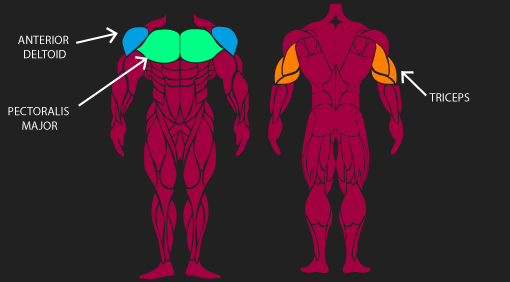

If we were to combine these findings with other acute data and reasoning, and it seems in all likelihood, push-ups likely have the capacity to produce similar hypertrophy of the pectoralis major, triceps, and anterior deltoid to the bench press.

For one, the push-up and bench press are biomechanically alike. Both involve shoulder horizontal flexion and extension, as well as elbow flexion and extension.

On top of this, the degree of range of motion that occurs is probably quite comparable between the two exercises. With a barbell bench press, the bar travels from a position of elbow lockout to a position where it contacts the chest region. Comparably, a regular push-up requires you to lower from a position of elbow lockout to a position where the chest region contacts the ground surface.

Considering these aforementioned points, its unsurprising acute electromyographic studies have, for the most part, found push-ups and bench pressing elicit similar muscle excitation of the agonistic muscles (pectoralis major, triceps, and anterior deltoid) when load-equated.

For those unaware, electromyographic studies (specifically surface electromyographic studies) strap up electrodes to a muscle to record its excitation during an exercise.

Remember, muscle fibers activate via electrical signals received from the nervous system. In essence, electromyography measures the electrical signals delivered to a muscle’s fibers, we call this muscle excitation.

Many people, including myself in the past, have mistakingly stated electromyographic studies measure muscle activation. Although muscle excitation does precede muscle activation, there are intermediate steps within the process that means it’s not sensible to call muscle activation and muscle excitation the same thing.

With that out the way, let’s briefly review the current electromyographic studies comparing the bench press and push-up.

A 2020 Canadian study by Alizadeh et al. found between a bodyweight push-up and an equivalently loaded flat barbell bench press, both performed with the same hand-spacing distance, excitation of the pectoralis major and anterior deltoid was similar during the concentric and eccentric phases of the exercises. However, lateral head triceps excitation seemed to be slightly lower during the concentric phase of the push-up versus the bench press.

Another 2020 study by Tillar and Ball had subjects perform four different load-equated conditions on the bench press and push-up.

The push-up was performed with bodyweight, a 10kg, 20kg, and 30kg weighted vest, while the flat barbell bench press was performed with four different loads that equated to each one of the push-up conditions.

Additionally, it’s worth mentioning the push-up was performed with handles using a pronated grip that replicated the grip used during the flat barbell bench press.

Excitation of the sternal and clavicular pectoralis major, long and lateral triceps brachii, were similar between both exercises at each load-equated condition. However, anterior deltoid excitation seemed to be greater during the concentric phase on the bench press versus the concentric phase of the push-up. Also, medial triceps head excitation was greater during the eccentric phase of the bench press compared to the eccentric phase of the push-up.

Finally, another paper by Tillar used the exact same design.

This time around, excitation of all of the measured regions of the pectoralis major, anterior deltoid, and triceps was similar between the load-equated push-up and bench press conditions.

Therefore, considering the totality of the existing electromyographic literature, though there are some differences and disagreements between studies, the push-up and bench press seem to induce similar excitation of the agonistic muscles when load-equated.

Now, it’s worth noting electromyographic studies, specifically the technique of electromyography, come with limitations and ample room for error. Furthermore, electromyographic data does not necessarily correlate with muscle hypertrophy outcomes.

Nevertheless, combining the current electromyographic literature with the two previously detailed longitudinal studies, as well as the fact both exercises are biomechanically alike, and it seems we have good grounds to hypothesize the push-up and bench press have the capacity to probably produce similar hypertrophy of the agnostic muscles.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Overloading the Push-up and Bench Press

Progressing further, it’s worth discussing a potential long-term problem with the regular push-up.

As you get stronger and build muscle from the stimuli provided by your exercises, you’re going to want to overload your exercises in some form in order to consistently maintain a high muscle-building stimulus. This is known as progressive overload.

With the flat barbell bench press, such overload can easily be accomplished. As you get stronger and bigger, you can increase the number of repetitions you perform with a given load, but more importantly, you also can increase the load you train with.

With the regular push-up, the number of repetitions you perform can be increased.

However, there likely comes a point where doing this becomes suboptimal for stimulating hypertrophy. Recall we detailed how the literature demonstrates loads between 30% and 80% one-rep max elicit similar hypertrophy outcomes, provided repetitions are executed 3 or fewer from the point of failure.

As explored in a previous article, it’s unclear if loads lighter than 30% one-rep max still can optimize hypertrophy. There are existing data suggesting it might not.

Very generally, individuals can perform approximately 35 repetitions with a 30% one-rep max load. Therefore, it follows that if an individual performs more than 35 repetitions on the regular push-up, no longer might muscle hypertrophy be optimally stimulated.

What’s the solution to this?

Overloading Push-ups With Harder Variations

One solution is to progress via using harder and harder push-up variations. Recall this was the strategy utilized in the Kotarsky study.

There exist an array of push-up variations with varying difficulty levels.

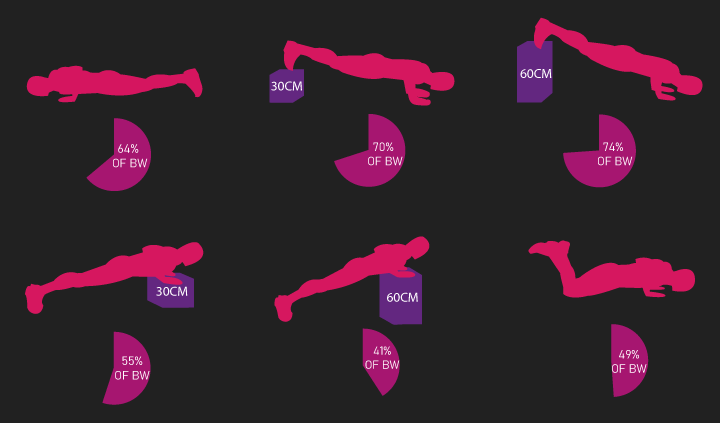

For example, a 2011 study by Ebben et al. examined what percentage of a person’s bodyweight they pushed during a few different push-up variations.

Approximately 64% of a person’s body weight was pushed during a regular push-up. Elevating your hands decreased this percentage while elevating your feet increased this percentage.

Furthermore, a kneeling push-up required a subject to push approximately 49% of their body weight.

This data can aid us in figuring out how an individual can progressively overload the push-up in the long run.

In addition to these aforementioned push-up variations, as seen in the Kotarsky study, single-arm push-up variations can also be highly useful for individuals who’ve progressed to a level where double-arm variations no longer adequately challenge them.

Other potentially notable push-up variations include explosive push-up variations, such as the clap or superman push-ups, push-ups with handles to increase the range of motion, as well as push-ups with gymnastic rings.

Having detailed all of this, there is potentially an unforeseen concern when an individual progresses via using harder and harder push-up variations.

Namely, different push-up variations likely distribute your bodyweight load across the agnostic muscles differentially. This might not align with what you want.

For example, as detailed a moment ago, elevating your feet has you push a higher percentage of your body weight versus a regular push-up. However, it’s also quite plausible push-ups with elevated feet shift the loading to your upper chest and anterior deltoids more, thereby possibly reducing the stimulus the mid to lower chest region experiences.

Additionally, many single-arm variations, potentially due to reduced shoulder horizontal flexion demands, may not recruit the chest to do the degree a person would want to. Moreover, although I’m not certain, single-arm variations are seemingly quite triceps dominant.

These points may be insignificant for those that mainly care about getting better and progressing with push-ups.

But for those using the push-up as a hypertrophy tool, this differential recruitment between different push-up variations may be slightly unideal.

Overloading Push-ups With Additional Weight

Weighted push-ups can probably solve this.

Specifically, aiming to progressively overload the push-up via additional weights (either through a weighted vest, plates, plates in a backpack, or some other method) can likely be highly effective for making the push-up a stable and solid muscle hypertrophy stimulus.

Recall earlier we presented two studies by Tillar that found weighted push-ups, for the most part, managed to elicit alike muscle excitation of the agonistic muscles to equivalently loaded bench pressing.

Now, in theory, there could come a point where weighted push-ups become slightly less practical.

Namely, performing 50-70kg weighted push-ups is probably feasible, but, beyond this point, it may become tricky to practically use heavier loads.

However, there still exist solutions.

With the additional weight, adding in paused repetitions, using deficit style push-ups to increase the range of motion, or even something like gymnastic rings can be tools to further progressive overload.

Additionally, although potentially more triceps dominant, working on weighted single-arm push-ups variations would plausibly still be a great stimulus for the pectoralis major and anterior deltoid.

It’s also worth noting again that repetitions up to 35, so long as they are executed 3 of fewer repetitions from failure, are effective for stimulating muscle hypertrophy.

As a result, progressing heavily weighted push-ups into the higher rep ranges will likely still be powerful for stimulating muscle hypertrophy.

For example, let’s say you’ve worked up to performing 50kg weighted push-ups for sets of 8 repetitions, and you wish to no longer add further external load as it isn’t practical. From here, your new goal might be to hit sets of 30 repetitions with this 50kg weighted push-up.

The main point I’m attempting to illustrate here is that although the bench press is far simpler to progressive overload in the long run, there are many routes in which an individual can successfully overload the push-up long-term.

Push-up and Bench Press Strength Carryover

Before closing out the article, I think there are some other interesting things worth mentioning.

The literature implies the push-up has a fantastic carry-over to bench press strength.

We’ve already overviewed the details of the Kikuchi and Nakazato, as well as the Kotarsky studies. Yet, I haven’t mentioned that in both of these studies, one-repetition max on the flat barbell bench press was evaluated before and after the training durations.

In both studies, increases in this measure were statistically similar between the push-up and bench press groups.

However, the percentage increases seem to meaningfully favor the bench press group. I think it’s probably likely the small sample sizes in both studies compromised the ability to detect this change as significant.

The reason I say this is because it’s of course very logical training the bench press is what would increase your bench press strength the most.

Even so, the data nevertheless demonstrates the push-up respectably improves bench press strength.

What about the reverse of this?

How well does bench press training carry over to push-up performance?

Let us briefly return to the Kotarsky study. Remember, they used a variety of push-up variations. Before and after the study, both the push-up and bench press groups were tested on which level they could comfortably perform.

By the end of the study, the push-up group managed to increase the level they could comfortably perform significantly, while although the bench press group also increased the level they could execute, it was much smaller in magnitude and statistically significantly less than the push-up group.

Hence, although bench press training can help push-up strength, it may not produce pronounced increases.

Although it’s worth remembering this Kotarsky study was only 4 weeks in duration, longer durations may change this.

Generally, I think it’s probably quite likely bench press training will have measurable positive effects on push-up performance long-term.

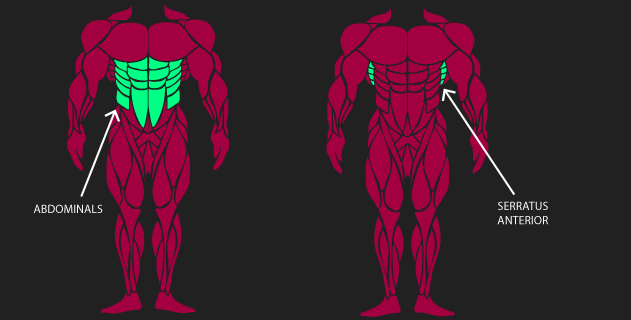

The Abdominals and Serratus Anterior

Finally, throughout this article, we’ve primarily been discussing the similarities between the push-up and bench press, namely their similar biomechanical demands, muscle excitation, muscle hypertrophy, and carry-over potential.

But, there still are notable differences between these two exercises.

The push-up likely recruits and develops the abdominal muscles to a greater extent than the flat barbell bench press.

Illustrating this, a 2014 study by Calatayud et al. found that a regular push-up produced significantly greater excitation of the rectus abdominis and external oblique versus the flat barbell bench press performed with an 85% one-rep max load.

These findings are logical. A push-up gets you into a plank position that necessitates abdominal recruitment to support and stabilize the trunk. Opposingly, the flat barbell bench press has you rest your trunk on a bench, meaning the abdominal muscles need not be recruited as much.

In addition to this, the push-up likely does a superior job to the bench press for developing the serratus anterior.

One of the functions of the serratus anterior is the protraction of the shoulder blades.

During a well-executed push-up, the shoulder blades move freely throughout the movement. Specifically, the shoulder blades retract during the lowering phase and protract during the lifting phase, enabling serratus anterior recruitment.

Conversely, a well-executed flat barbell bench press typically has your shoulder blades retracted and pinned down into the bench, meaning no protraction occurs.

Takeaway Points

That brings us to the end of the article.

To make everything crystal clear, let’s establish a few key takeaway points:

- Combining the electromyographic literature with the two longitudinal studies, as well as the biomechanical similarities between the push-up and bench press, and we seem to have good grounds to hypothesize both exercises likely have the capacity to produce similar hypertrophy of the agonistic muscles.

- Overloading the bench press in the long-term is simple, the load can be increased.

- On the other hand, the push-up is a little more tricky to overload long-term.

- One solution is to progress via using harder and harder push-up variations. Although, a potential concern with this is that the different push-up variations may differentially distribute the load amongst the agonistic muscles. For some, this may be unideal.

- Probably the best resolution to this is to train with weighted push-ups.

- Current data implies the push-up has a great carryover to bench press strength. Whether the reverse of this is true isn’t entirely clear.

- Despite there being many similarities between the two exercises, there are some noteworthy differences. The push-up recruits the abdominals and serratus anterior to a greater extent than the barbell bench press.

- Finally, although we’ve been directly comparing the bench press to the push-up in this article. It’s important to remember in the real world, you do necessarily have to pick between either. Both can successfully be performed in a training plan.

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.

What really makes the bench press a much more superior muscle and strength builder than the pushup, is the fact that a barbell can be loaded with weights that would otherwise be impractical to attempt in a weighted pushup.

And secondly, bench pressing one’s own bodyweight is much more difficult than performing a pushup.

And lastly, if pushups were that great, did any of the subjects in those “studies” have the pectoral development of a prime Arnold Schwarzenegger? Or has any person ever built the upperbody mass of a prime Ronnie Coleman, or the newly crowned Mr Olympia Big Ramy, by just doing pushups?

Those are the questions that need to be addressed, instead of siting a bunch of “studies” that don’t involve elite-level subjects.

“Citing”

I agree the bench press is much simpler to overload. However, as I attempted to show in this article, the push-up could still be overloaded to a great extent. Numerous push-up variations can be used as a progression model (similar to what they did in the Kotarsky et al. study).

For building muscle, reps between 5 and 35 produce similar muscle growth, provided those reps are performed to failure (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28834797/). I’ve never seen anyone perform 30 reps of one-arm push-ups. I’m quite sure that if an individual could, their chest, triceps, and deltoid development would be impressive.

Bench pressing your bodyweight is certainly harder than a push-up. Nowhere in this article did I say it was not. If you head over to the article on how much weight you press during a push-up, you would see a standard push-up has you pressing roughly 64% of your body weight.

Of course none of the subjects would have had the pectoralis development of Arnold. The subjects in Kikuchi and Nakazato study had a minimum of 1 year training experience, while the subjects in the Kotarsky et al. study only had 2-6 months of training experience.

Furthermore, How many people on this earth have the pectoralis development of Arnold or Ronnie? I think you’re failing to factor in genetics and anabolics.

The point of this article was to evaluate how push-ups compare to bench pressing when researchers best attempt to load equate the two exercises. As detailed in the article, the current evidence would suggest both are similarly effective for hypertrophy.

Again, as I tried to allude to in this article, in the long run, progressive overload with the bench press is simpler. But I believe the Kotarsky et al. study demonstrates the use of push-up variations could be effective for overloading in the long term.

Basically what I’m saying, is that bench pressing will produce far greater mass results than pushups, when both are trained to an elite level, everything else equal. When you compare the top gymnasts/calisthenics gurus (many of whom use PEDS as well), to the top IFBB pros, the visual difference is obvious, especially in the legs. That’s pretty much the gist of it.

I don’t think it’s necessarily sensible to compare gymnastics/top calisthenic athletes to IFBB pros. I highly doubt that for those on anabolics, their stacks would be identical or similar. Further, IFBB pros are likely gifted with the elite of the elite genetics for putting on muscle mass. On the other hand, top gymnastics may be gifted with the elite of the elite genetics for maximizing relative strength. The year-round training and nutrition plans (particularly the amount of time in a caloric surplus) between gymnastics and bodybuilders also likely differ to a significant degree.

The point here is that everything else is very much NOT equal when comparing two different elite levels.

As I’ve attempted to outline in this article, the push-up and bench press are biomechanically comparable. So long as individuals find a way to overload the push-up, in the long run, I simply cannot see why the push-up would be inferior to the bench press. The longitudinal research supports this, the push-up and bench press appear to induce similar hypertrophy.