In this article, we’re going extremely deep into the science comparing different training frequencies and splits for muscle hypertrophy.

Briefly, full-body workouts, needless to say, involve training all muscle groups in one session. Anywhere from 2 to 5 full-body training sessions are commonly performed per week.

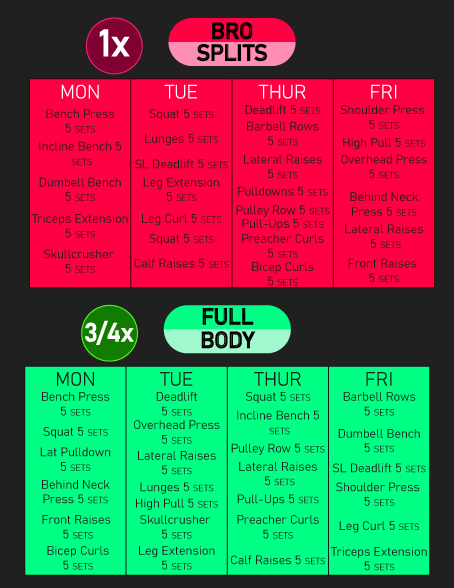

Bro-splits isolate muscle groups on different days of the week. Muscle groups are typically trained with a frequency of once or twice a week here.

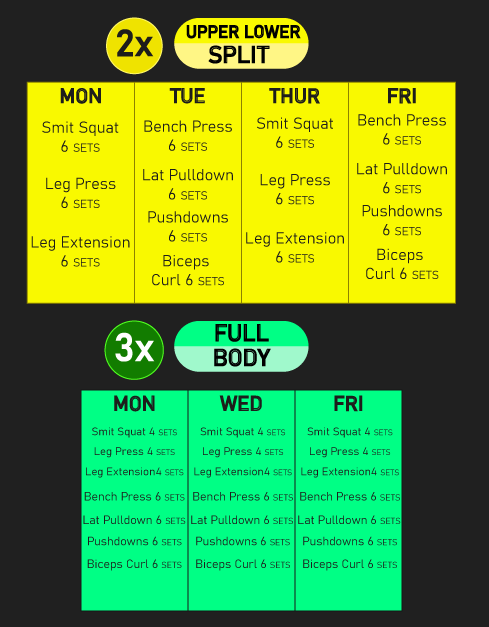

Upper/lower splits train your upper and lower body muscles on separate days. Commonly, 2 upper and lower body sessions are performed weekly, resulting in you training muscle groups at a twice per week frequency.

Though performing 3 upper and lower body sessions each week is also possible, this results in you training your muscle groups with a three times per week frequency.

Finally, push/pull/legs train your pushing, pulling, and leg muscles on separate days. Such a schedule means muscle groups are hit with a frequency of twice per week.

Before diving into the science, let us overview some history of training splits.

Table of Contents

Part I: House of History

Traveling back to the 1900s to 1950s, surprisingly, full-body training seemed to be the norm.

It appears Eugen Sandow, often called “the father of bodybuilding”, and other legends within the sport, like Reg Park (an idol of Arnold), trained with full-body routines.

For example, I stumbled across a newspaper article written by Reg Park himself, detailing his training preparation for the 1958 Mr. Universe competition.

Part of this prep consisted of 3 full-body weekly workouts.

By the 1950s-60s and onwards, however, the rise of bro-splits was ignited for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, it appears the Weider brothers, businessmen with their own supplements, magazines, and bodybuilding competitions, are credited with popularising bro-splits through their magazine’s writings. Partly, it seems the Weider brother’s promotion of bro splits was to help distinguish themselves from other businessmen in the fitness world.

Secondly, while evidence exists of occasional bodybuilding competitions before the 1930s, it was in the decades after bodybuilding competitions become more regular and prominent. As an article by BarBend puts it “If no bodybuilding competitions exist, focusing on your biceps peaks seems somewhat pointless.” Thus, the rise of regular and prominent bodybuilding competitions likely also contributed to bro-splits becoming more favorably looked upon by bodybuilding enthusiasts.

Thirdly and finally, during what’s now sometimes called the “golden era of bodybuilding”, legendary figures like Arnold and Frank Zane were known to train and promote bro splits.

In Arnold’s encyclopedia of bodybuilding, published in 1985, bro-split routines were detailed.

Back to today, the popularity of bro-splits seems to remain in the bodybuilding sphere.

A 2022 study by Hackett had 235 competitive bodybuilders complete an online survey, and found 85.5% of them used split routines.

It may be worth also noting 53.6% of all surveyed bodybuilders used performance-enhancing drugs.

With regards to upper/lower splits and push/pull/leg splits, I was unfortunately unable to find any resources detailing their history.

Nevertheless, let us transition to examining what the research has to say on the optimal training frequency for muscle hypertrophy.

Part II: Very Important Note

It’s very important to note all the research to be explored has assessed how different training frequencies impact muscle growth while all other weekly training variables (including weekly sets per muscle group) are kept the same.

For example, researchers may get one group to train their muscle groups once per week and compare this to another group of subjects training their muscle groups three times per week.

Both of these groups ultimately perform the same weekly sets on the same exercises and thus achieve the same weekly set numbers per muscle group.

Keeping all other weekly training variables the same ensures they do not confound our findings, as we’re trying to isolate the effect of training frequencies and splits.

This is important, as the number of weekly sets per muscle group performed can impact the amount of hypertrophy produced.

Nevertheless, some individuals believe in the real world, higher training frequencies are a practical way to increase the number of weekly sets performed per muscle group. This is a fair point, and it’s something we’ll address a little later on.

With that out the way, let’s get on to the literature.

Part III: Outdated Data

In 2016, a meta-analysis by Schoenfeld et al. combined the results of all the existing studies at that time point on training frequency.

It was found with all other weekly training variables equal, training a muscle group twice per week was better than once a week. Due to limited data, the researchers couldn’t speculate on if training a muscle group three or more times per week provided more benefit.

To this day, many people seem to run with this data saying bro-splits are scientifically inferior, as bro-splits typically involve training a muscle group once a per week.

Full-body workouts, upper/lower splits, and push/pull/legs splits were thought to be superior as all these involve training a muscle group at a frequency of two or more times per week.

Yet, there are major problems here. This analysis was conducted 6 years ago and only involved 7 studies.

Fortunately, Schoenfeld et al. conducted an updated meta-analysis in 2019. This is currently the most up to data official meta-analysis examining training frequency and muscle hypertrophy.

13 studies were included in the analysis this time around.

It was found with all other weekly training variables constant, training frequency did not affect muscle growth. That is, no particular training frequency was superior for muscle hypertrophy.

An important point is out of the 13 studies included, 11 had subjects train with a total of 12 weekly sets per muscle group or fewer.

Thus, the most accurate conclusion from this analysis is when training with a total of 12 or fewer weekly sets per muscle group, no particular training frequency or split seems to be superior.

Bro splits, full-body workouts, upper/lower splits, and push/pull/legs splits are all viable.

Let’s briefly examine a few studies included in the analysis underscoring this point.

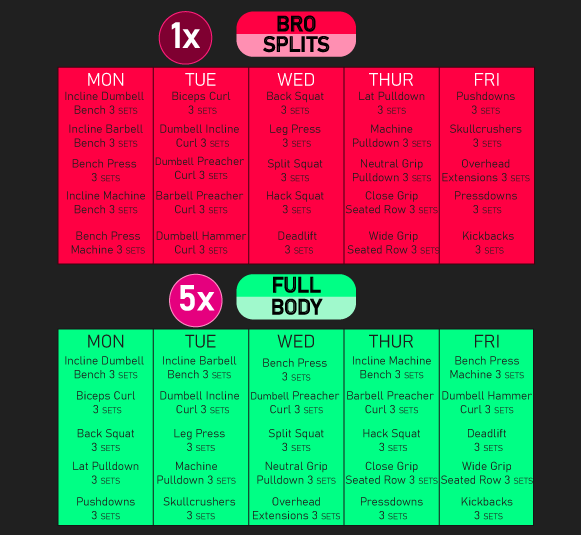

Gomes et al. recruited 23 trained men with an average bench press one-rep max of 103kg and an average squat one-rep max of 132kg.

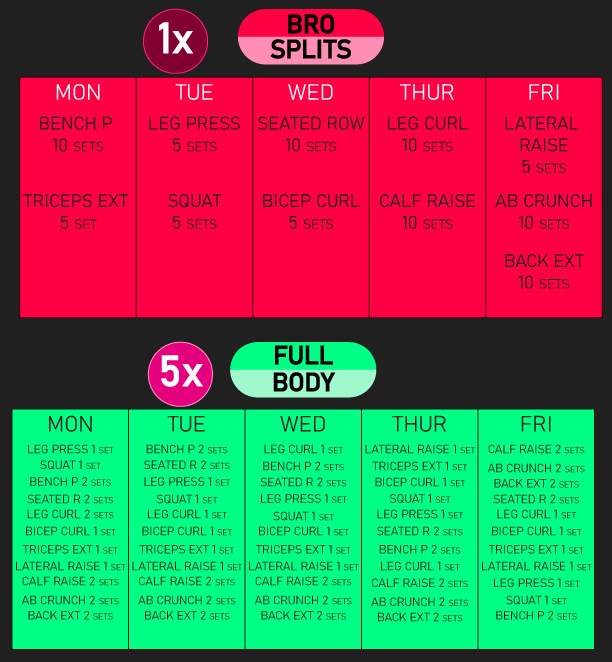

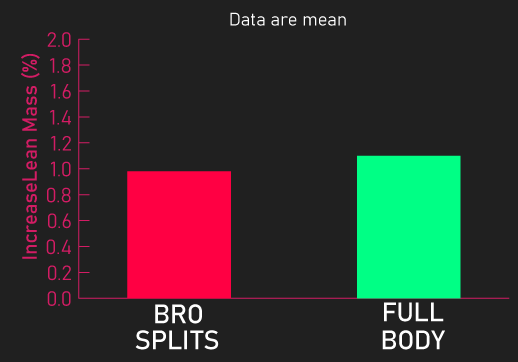

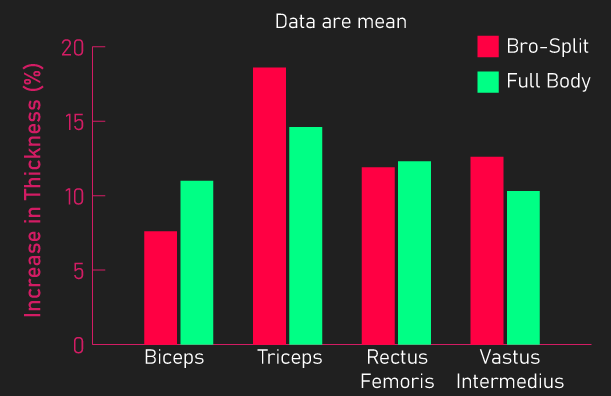

One group used bro-splits that trained muscle groups at a frequency of once per week. A second group used full-body workouts that trained muscle groups at a frequency of five times per week.

Both groups accumulated 10 weekly sets for each trained muscle group.

Although, with the triceps and biceps, if you count compound exercises in addition to the isolation exercises, both these muscles were trained with 15 weekly sets each.

Nevertheless, after 8 weeks of training, increases in lean mass were similar between both groups.

Another study by Ochi et al. recruited untrained subjects and had them train the leg extension only.

One group performed 6 sets on one day per week. Another group performed 2 sets across 3 days per week.

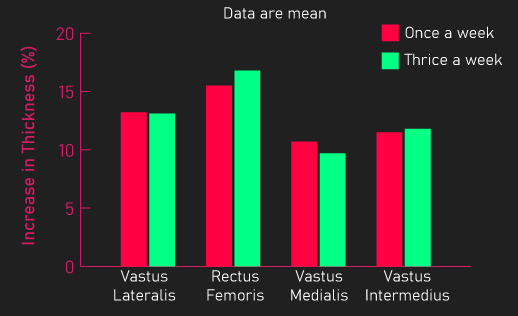

After 11 weeks of training, increases in quadriceps thickness were similar between both groups.

Therefore, this study potentially suggests with low weekly set numbers, training a muscle once a week (as done with bro-splits) may be similarly effective to training a muscle three times per week (as done with full-body workouts).

Regarding upper/lower and push/pull/legs splits, we know these typically train a muscle at a frequency of twice per week. Again, with 12 or fewer weekly sets per muscle group, there is likely nothing superior or inferior with a twice per week frequency.

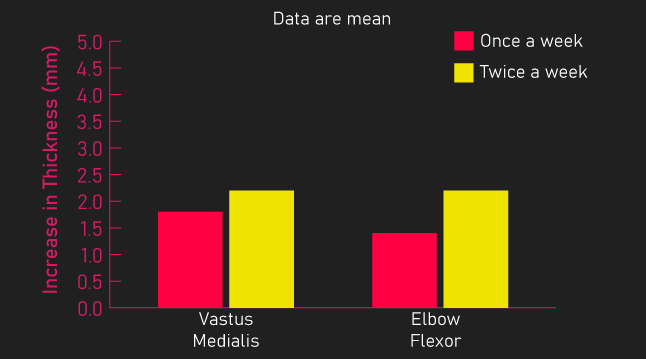

As an example, Yue et al. recruited 18 trained men with an average bench press one-rep max of 77kg and an average squat one-rep max of 103kg.

One group trained their muscle groups with a frequency of once per week (except the triceps and biceps which were technically trained twice per week), while another group trained their muscle groups with a frequency of twice per week (except the biceps and triceps which were technically trained four times per week).

Both groups trained all muscle groups with 4-12 weekly sets. However, if you count compound exercise sets toward triceps and biceps weekly set numbers, the biceps were trained with 16 weekly sets while the triceps were trained with 24 weekly sets.

After 6 weeks of training, both groups did not statistically differ in vastus medialis and elbow flexor thickness gains.

So, it seems when performing 12 weekly sets per muscle group or fewer, all training splits and frequencies appear viable and similarly effective for building muscle.

Before moving on, if you’re curious about creating an effective training program for muscle hypertrophy, our high quality partner Alpha Progression can help. It can generate a highly effective program for you, track your workouts live with in-built progression recommendations, provide graphs displaying your long term progress, and it has a massive exercise database with more than 550 exercises.

Click HERE (the link opens in a new tab) to get a free 2 week trial of the apps features. If you like it and go beyond, the link also gives you 20% off a subscription!

We never promote trash at the House of Hypertrophy, so rest assured the app is high quality. The reviews speak to this, 4.8 starts (based on more than 7,000 reviews) on Google play, and 4.9 stars in Apple’s store (based on nearly 400 ratings).

Part IV: What About Higher Volumes?

The burning question is what about when training with more than 12 weekly sets per muscle group?

Does training frequency matter in this situation?

Theoretically, there could be a limit to the number of effective sets you can perform for a muscle group per session. Thus, when training a muscle group with a fair number of weekly sets, using a training frequency greater than once per week may be required

Indeed, two studies published in 2020 by Barbalho et al. provided potential evidence for this (one and two).

Both studies were designed the same, but one study was done on trained men while the other on trained women.

Subjects only trained their muscle groups at a frequency of once per week.

One group trained with 5 weekly sets per muscle group, the second with 10 weekly sets, the third with 15 weekly sets, and the fourth with 20 weekly sets.

As subjects trained muscle groups with a frequency of once per week, the number of weekly sets performed for a muscle group was equivalent to the number of sets performed for a muscle group per session.

Overall, 5 to 10 sets were sufficient for increasing muscle size. In fact, the data of the study shows slightly worse muscle size increases when training with 15 to 20 sets.

Hence, this data potentially indicates on a per session basis (as remember, the study used a frequency of once per week), performing between 5 to 10 sets per muscle group might be the limit to the amount of productive volume you can perform per session.

If you want to perform more than 5-10 weekly sets for a muscle group, distributing the weekly sets across a higher frequency of days may be necessary.

However, we have a problem.

These two studies by Barbalho et al. have since been retracted, probably because the data presented in the study was not legitimate.

It’s been established many studies conducted by Barbalho et al. contain atypical and improbable data.

So, these Barbalho studies cannot help our quest to establish the optimal training frequency with higher weekly volumes.

Fortunately, we do have other valid data.

Recall in the Schoenfeld et al. 2019 meta-analysis, 11 of the 13 included studies in the analysis had subjects train with 12 or fewer weekly sets per muscle group.

Meaning 2 studies had subjects train with more than 12 weekly sets per muscle group.

Moreover, since 2019, 3 additional studies have been published comparing different training frequencies when subjects train with more than 12 weekly sets per muscle group.

So in total, we currently have 5 studies.

Allow us to overview them.

Evangelista et al. recruited untrained men with an average 60kg bench press one-rep max and an average 87kg back squat. These numbers, particularly the squat numbers, are quite impressive for untrained individuals.

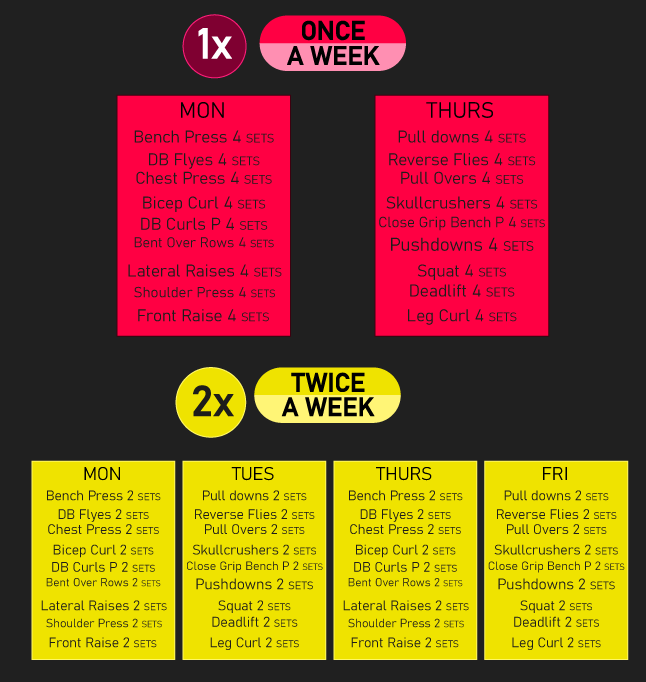

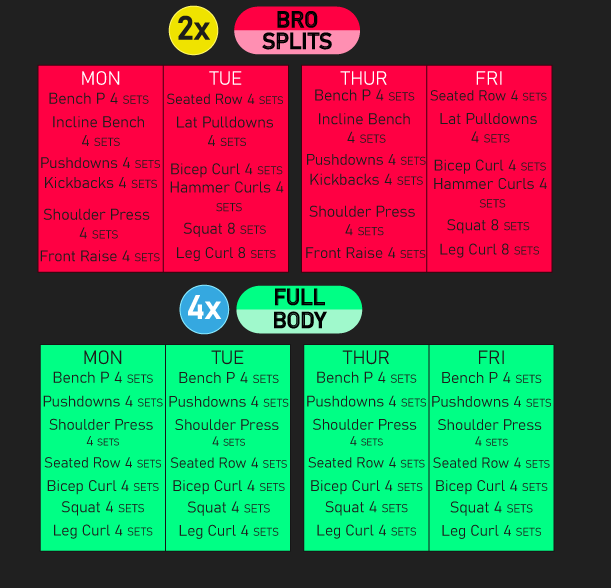

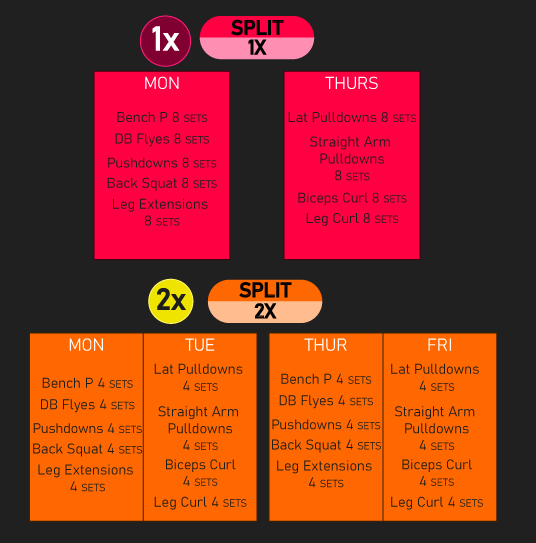

Anyway, a bro-split routine group trained their muscle groups at a twice per week frequency, while a full-body group trained muscle groups at a four times per week frequency.

Both groups accumulated 16 weekly sets per muscle group

However, if we include compound exercise sets towards the weekly set biceps and triceps counts, the triceps were trained with a whooping 40-48 weekly sets, while the biceps were trained with 32 weekly sets.

Now, although both groups performed the same weekly set numbers for their muscle groups (except for the triceps), exercise selection slightly differed between the bro split and full-body groups. The bro split group used a little more exercise variety.

Nonetheless, after 8 weeks of training, increases in quadriceps, triceps, and biceps thickness were similar between both the bro-split and full-body groups.

Suggesting even with higher weekly volumes, bro-splits may be comparable to full body workouts.

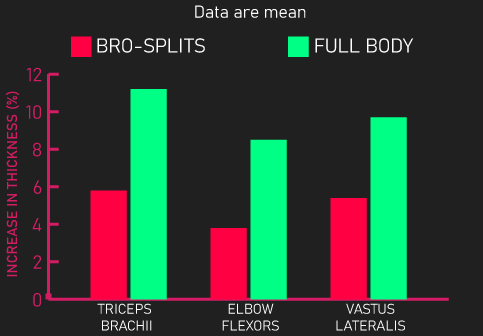

Brigatto et al. also suggest training frequency may not matter much with higher weekly volumes.

These researchers recruited trained men whose average bench press one-rep max was 94kg and squat one-rep max was 125kg.

Two groups trained with a split routine. One group trained their muscle groups with a frequency of once per week while the second group trained their muscle groups with a frequency of twice per week.

Both groups accumulated 16 weekly sets per muscle group. Though, if we counted compound exercises toward biceps and triceps weekly set counts, both these muscles were trained with 24 weekly sets.

After 8 weeks of training, increases in triceps, biceps, vastus lateralis, and anterior quadriceps thickness were similar between both groups.

Suggesting with higher weekly volumes, a frequency of once per week may be similar to a twice per week.

Thus, combining this Brigatto study with the Evangelista study, they potentially indicate training splits and frequency may not matter with higher weekly volumes either.

However, the remaining three studies do not support this conclusion.

Zaroni et al. recruited men with an average bench press one-rep max of 99kg and an average squat one-rep max of 109kg.

A bro-split group trained their muscle groups at a once per week frequency (though the triceps and biceps would have been trained twice per week if we consider compound exercises). A full body trained their muscle group at a frequency of five times per week.

Both groups accumulated 15 weekly sets for all muscle groups. But for the biceps and triceps, if we count compound exercises, both these muscles were trained with 30 weekly sets.

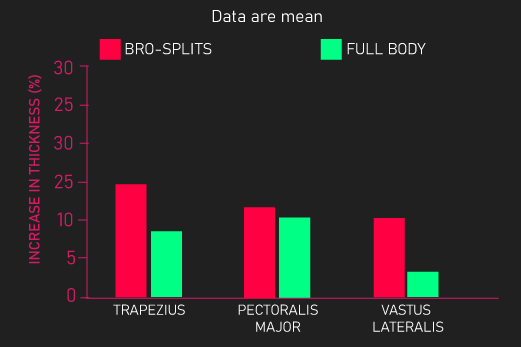

After 8 weeks of training, increases in triceps, biceps, and vastus lateralis thickness were superior for the full-body group versus the bro-split group.

Indicating with higher weekly volumes, full-body training may be superior to bro-splits.

Yet, another study by Bartolomei et al. somewhat directly conflicts with this study.

These researchers recruited trained men with an average bench press one-rep max of 96kg and an average squat one-rep max of 108kg.

A bro-split group trained their muscle groups at a frequency of once per week. Though the triceps, considering compound exercises, would have been trained twice per week. A full-body group trained their muscle group at a frequency of three to four times per week.

Both groups accumulated 15 weekly sets for the chest and 20 weekly sets for their quadriceps, while the trapezius was trained with around 25 indirect weekly sets.

After 10 weeks of training, increases in thickness of the chest were similar between both groups. But, increases in thickness of the vastus lateralis and trapezius were superior for the bro-split group.

Suggesting bro-splits overall to be superior to full body training with higher weekly volumes, thus somewhat conflicting with the Zaroni et al. study.

Making things even more confusing, we have the final study by Lasevicius et al.

These researchers recruited trained men with an average bench press one-rep max of 79kg and an average back squat one-rep max of 161kg.

An upper/lower split group trained their muscle groups with a frequency of twice per week. A full-body group trained their muscle groups with a frequency of three times per week.

Both groups accumulated 36 weekly sets for the quadriceps, and 12 weekly sets for the triceps and biceps. However, if we counted compound exercise sets towards triceps and biceps weekly sets, both of these muscles were trained with 24 weekly sets.

After 10 weeks of training, increases in thickness of the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, biceps, and triceps were superior for the upper/lower split group versus the full-body group.

Suggesting with high weekly volumes, a frequency of twice per week (as achieved with upper/lower splits) is more beneficial than a frequency of three times per week (as achieved with full-body workouts).

When combining all of these 5 studies, it’s utterly confusing as the findings are conflicting.

2 studies suggest training frequency did not impact hypertrophy, 1 suggests full-body workouts are superior to bro-splits, another suggests bro-splits are superior to full body workouts, and the final study indicates upper-lower splits are better than full-body workouts.

Part V: What Explains These Results?

Needless to say, the 5 studies were far from identical. The precise training details between the studies differed, this could go some way toward explaining the conflicting results between studies.

At this time, it’s going to be impossible for us to figure this out.

Even so, individual differences could also go some way to explaining the conflicting data, and this is a very important point.

There’s reason to believe different individuals can respond best to different training frequencies or splits.

One paper by Damas et al. supports this.

19 untrained men were recruited and had one of their legs assigned to a high-frequency condition and their other leg assigned to a low-frequency condition.

Both legs were trained on the unilateral leg extension with each session consisting of 3 sets of 9-12 repetitions to failure.

With the high-frequency leg, subjects did this 5 times per week. With the low-frequency leg, subjects did the session 2 or 3 times per week.

This design also meant volume was not equated. The high-frequency condition would have accumulated 15 weekly sets for the quadriceps, while the low-frequency condition would have accumulated 6 to 9 weekly sets for the quadriceps.

Before and after the 8 weeks of training, vastus lateralis cross-sectional area was measured for both legs.

6 subjects experienced the best vastus lateralis cross-sectional area increases with their high-frequency condition leg, 7 experienced the highest vastus lateralis cross-sectional area increases with their low-frequency condition leg, and the remaining 6 saw similar vastus lateralis cross-sectional area increases between both the high and low-frequency legs.

Based on this, it seems some individuals may grow more with higher frequency training, others with lower frequency training, and some may display no difference between higher and lower frequencies.

Again, the number of weekly sets was not equated in this study, so this confounds the conclusion just made.

Nevertheless, I think it’s quite likely different training frequencies and splits may work best for different individuals.

Moreover, these individual differences may be more important when discussing higher volumes (namely when people perform more than 12 weekly sets per muscle group).

If true, this may explain why the research is more consistent in finding when performing 12 or fewer weekly sets per muscle group, training frequency and splits have no impact on muscle growth.

And it also explains why when performing more than 12 weekly sets per muscle group, the findings of the 5 studies are largely conflicting.

Part VI: Important Limitations With the Data

With the 5 studies examining the influence of different training frequencies when training with more than 12 weekly sets per muscle group, a vital consideration exists.

Most of the studies had subjects use short rest interval durations between sets (1 to 1.5 minutes) in their sessions.

Except for the Bartolomei study, which had subjects rest 2 minutes between sets, which might potentially be just about a long rest interval.

Nevertheless, why is the fact most of the studies used short rest intervals important?

It’s because short rest intervals make each set less effective for building muscle.

A couple of studies demonstrate with all other training variables equal, resting 2.5-3 minutes between sets produces more muscle hypertrophy than resting for 1.5 minutes or less.

Now, the studies finding this largely used compound exercises, and it is likely this conclusion (2.5-3 minutes of rest between sets is superior) applies to compound exercises only. Even so, we know the 5 studies overviewed earlier used numerous compound exercises.

When using short rest intervals between compound exercise sets (1.5 minutes or less), you likely have to perform extra sets to receive similar muscle hypertrophy.

A study by Longo et al. demonstrated this.

When performing 3 sets of repetitions to failure per session, resting for 3 minutes between sets produced greater increases in quadriceps cross-sectional area versus resting for 1 minute between sets.

But, when performing 4 to 5 sets of repetitions to failure with 1-minute rest between sets, muscle growth was similar to performing 3 sets of repetitions to failure with 3 minutes of rest between sets.

How does this information tie into training frequency?

Earlier we stated there could be a limit to the effective number of sets you can perform for a muscle group per session.

If true, the limit would likely be LOWER when using long rest intervals between sets. This is because long rest intervals between sets make each set more effective.

The limit would probably be HIGHER when using short rest intervals between sets, as short rest intervals between sets make each set less effective for building muscle.

As most of the 5 studies used short rest intervals, maybe this explains why many of them found bro-splits or lower frequencies to be viable.

As the limit to the number of effective sets for a muscle group per session would be higher with shorter rest intervals, perhaps none of the subjects training with bro splits or lower frequencies exceeded this limit.

If the studies used longer rest intervals instead, more of them might find bro-splits or lower frequencies to be suboptimal.

The subjects’ training with bro splits or lower frequencies might exceed the limit to the number of effective sets that can be performed for a muscle group per session, as this limit would be lower when using long rest intervals.

To rephrase all this, if the studies exploring how different training frequencies compare when training with more than 12 weekly sets per muscle group used longer rest intervals (2.5-3 minutes), they may find lower frequencies to be inferior as subjects would exceed the limit to the number of effective sets that can be performed for a muscle group each session.

Of course, this is very much speculation.

But, is there any research that could help verify anything we’ve just said?

There is indeed some potential data.

A study by Ogasawara et al. subjected the gastrocnemius of rats to sets of 10 electrically induced muscle contractions, using 3 minutes of rest between sets (a long rest interval).

They found muscle protein synthesis progressively increased up to performing 10 sets of this per session. But, muscle protein synthesis was less when performing 20 sets per session.

Suggesting anywhere from 10 to 20 sets may be the limit to the number of effective sets that can be performed for a muscle group per session.

Of course, limitations of this data are rats were studied and muscle protein synthesis measurements were taken, not actual muscle growth.

Another study by Damas et al., conducted on humans, found little difference in myofibrillar protein synthesis between training with 8 and 12 sets for the quadriceps in one session.

2 minutes of rest between sets was used, which is probably just about a long rest interval.

Therefore, this study suggests there’s little benefit to performing more than 8 sets for a muscle group per session with longer rest intervals.

Again though, this data is limited as it only explored protein synthesis, not actual muscle growth.

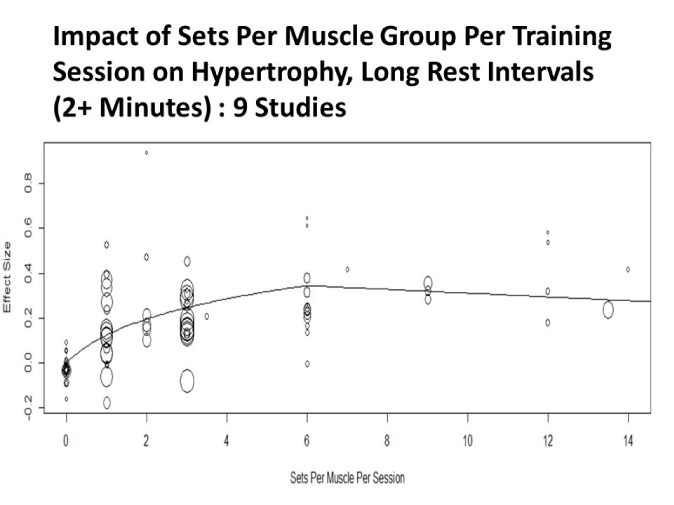

Finally, an analysis by James Kreiger examined the current research on set numbers and found when resting 2 or more minutes between sets, muscle growth tended to plateau beyond performing 6-8 sets for a muscle group per session.

However, a limitation is this analysis included studies done on trained and untrained individuals, and much of the studies done on untrained individuals did not exceed 6 sets for a muscle group per session.

So much of the data points on the left from untrained individuals may bias the curve as untrained individuals have greater muscle growth capacity.

Furthermore, it’s possible weekly set numbers could also confound this analysis. Much of the datapoints to the right of the graph come from studies having subjects perform a high number of total weekly sets for a muscle group.

Thus, the lower muscle growth in this area could be a result of performing too many weekly sets (and perhaps under recovering) rather than performing too many sets on an individual session basis.

Even so, when combining the Ogasawara et al. study, the Damas et al., study, and the analysis by James Kreiger, 6-10 sets for a muscle group per session might be the limit.

But again, these data have their respective limitations. Future research is unquestionably required to examine things further.

As a final counterpoint, recall the Bartolomei et al. study had subjects rest 2 minutes between sets (which may just about be a long rest interval), yet this study found bro-splits were overall superior to full body workouts.

In fact, the bro-split group was performing 20 sets for the quadriceps in one session.

Thus, this study might oppose the suggestions we’ve made, perhaps there’s no practical limit to the number of effective sets that can be performed for muscle group per session. But this is only a single study too.

Part VII: Practical Considerations

Making things crystal clear so far, we’ve established when training with 12 or fewer weekly sets per muscle group, training frequency does not seem to impact muscle hypertrophy.

When training with more than 12 weekly sets per muscle group, data conflicts on the optimal training frequency. Individual differences could explain these conflicting findings.

Yet, a limitation with this data is short rest intervals were used. If they used longer rest intervals, lower frequencies could be suboptimal, but this is currently speculative.

Moving on, we know all the training frequency research explored so far kept all other weekly training variables constant, including the number of weekly sets performed for a muscle group.

This was simply because we want to isolate the effects of training frequency and not have other training variables confound stuff.

But away from the lab and in the real world, increasing training frequency can be a tool to help increase the number of weekly sets you perform for a muscle group.

For example, a person might be performing 2 full-body workouts per week, so each muscle group is trained at a twice per week frequency.

Then, to further increase the number of weekly sets performed for their muscle groups, they add a third full-body workout per week.

Now, why would a person even want to increase the number of weekly sets performed for a muscle group?

Some evidence suggests modestly increasing the number of weekly sets performed for a muscle group in trained individuals can accelerate muscle hypertrophy.

Aube et al. found in men with at least 3 years of training experience, there was no statistical difference in mid and anterior thigh growth between performing 12, 18, or 24 weekly sets for the quadriceps.

However, when the researchers split all subjects into either a low responder, high responder, or moderate responder group, something interesting was found.

Remember, the subjects of this study had at least 3 years of training experience and were training before the study took place.

It seems that those that grew their mid anterior thigh the most in the high responder group had increased their weekly sets by the greatest number relative to what they were doing before the study.

Specifically, they were performing an average of 6 more weekly sets for the quadriceps. For the moderate responders, they were performing an average of 4 more sets relative to what they were before the study, and for the low responders, they were only performing around 1-2 more sets than what they were doing before the study.

In other words, increasing the weekly sets performed for a muscle group seems to be an effective way to accelerate muscle hypertrophy for these trained folks.

Another study by Scarpelli et al. recruited trained men and had them train the unilateral leg extension and unilateral leg press twice per week for 8 weeks.

With one leg, each subject individually performed 20% more weekly sets for their quadriceps than what they were doing before the study.

With their other leg, all subjects performed a prescribed number of weekly sets for the quadriceps, this was 22 weekly sets.

It was found vastus lateralis growth was greater for the leg performing 20% more weekly sets.

Put differently, a progressive increase in weekly sets (20%) seems to be beneficial for muscle growth.

An interesting point is for 8 out of the 16 subjects, the prescribed number of weekly sets (22 weekly sets) was actually more than 20% of the weekly sets they had been performing for their quadriceps before the study (it ranged from being 30% to 120% more weekly sets than usual for these subjects).

Yet, results still favored the leg that performed 20% more weekly sets. This finding emphasizes that larger jumps (30-120%) in weekly sets are not necessarily better than more modest (20%) increases in weekly sets for muscle hypertrophy.

In summary, modestly increasing the number of weekly sets you perform for a muscle group seems to be an effective way to accelerate muscle hypertrophy in trained individuals.

Increasing training frequency can be a tool to help increase your weekly set numbers.

Part VIII: Takeaways

When training with 12 or fewer weekly sets per muscle group, training frequency does not seem to impact muscle hypertrophy.

When training with more than 12 weekly sets per muscle group, data conflicts on the optimal training frequency. Individual differences could explain these conflicting findings.

Yet, a limitation with this data is short rest intervals (1-1.5 minutes) were mainly used. If they used longer rest intervals (2.5 to 3 minutes), lower frequencies could be suboptimal, but this is currently speculative.

Finally, outside of the lab and in the real world, increasing training frequency can probably be an effective tool to increase weekly set numbers for a muscle group. This is notable as some evidence indicates in trained individuals, modestly increasing weekly set numbers can accelerate muscle hypertrophy.

Remember to feel free to check out the Alpha Progression App if you’re interested. Also feel free to check out our free bench press e-book below.